Congestion Management Program 2025

Executive Summary

Introduction

Every two years, the San Francisco County Transportation Authority (SFCTA) as the designated county Congestion Management Agency (CMA) for San Francisco prepares the San Francisco Congestion Management Program (CMP). This program is conducted biennially in accordance with state law to monitor congestion, inform policy and long-range planning efforts, and adopt strategies for mitigating traffic congestion that falls below certain thresholds as warranted.

The CMP combines the traffic Level of Service (LOS) and multimodal performance elements required under state CMP legislation, reflecting the legislation’s requirement that LOS be included as one of several multimodal performance measures, and that automobile-focused metrics alone, such as LOS, result in a limited view of transportation issues. For this reason, SFCTA’s approach is guided by San Francisco’s long-standing Transit First policy and emphasis on accessibility for the movement of people and goods by transit, bicycling, walking, and shared modes, while maintaining motor vehicle circulation.

State CMP legislation aims to increase the productivity of existing transportation infrastructure and encourage more efficient use of scarce new dollars for transportation investments, to effectively manage congestion, improve air quality, and facilitate sustainable development. The purpose of the 2025 San Francisco Congestion Management Program is to:

- Define San Francisco’s performance measures for congestion management;

- Report congestion monitoring data for San Francisco to the public and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC);

- Describe San Francisco’s congestion management strategies and efforts; and

- Outline the congestion management work program for the two upcoming fiscal years.

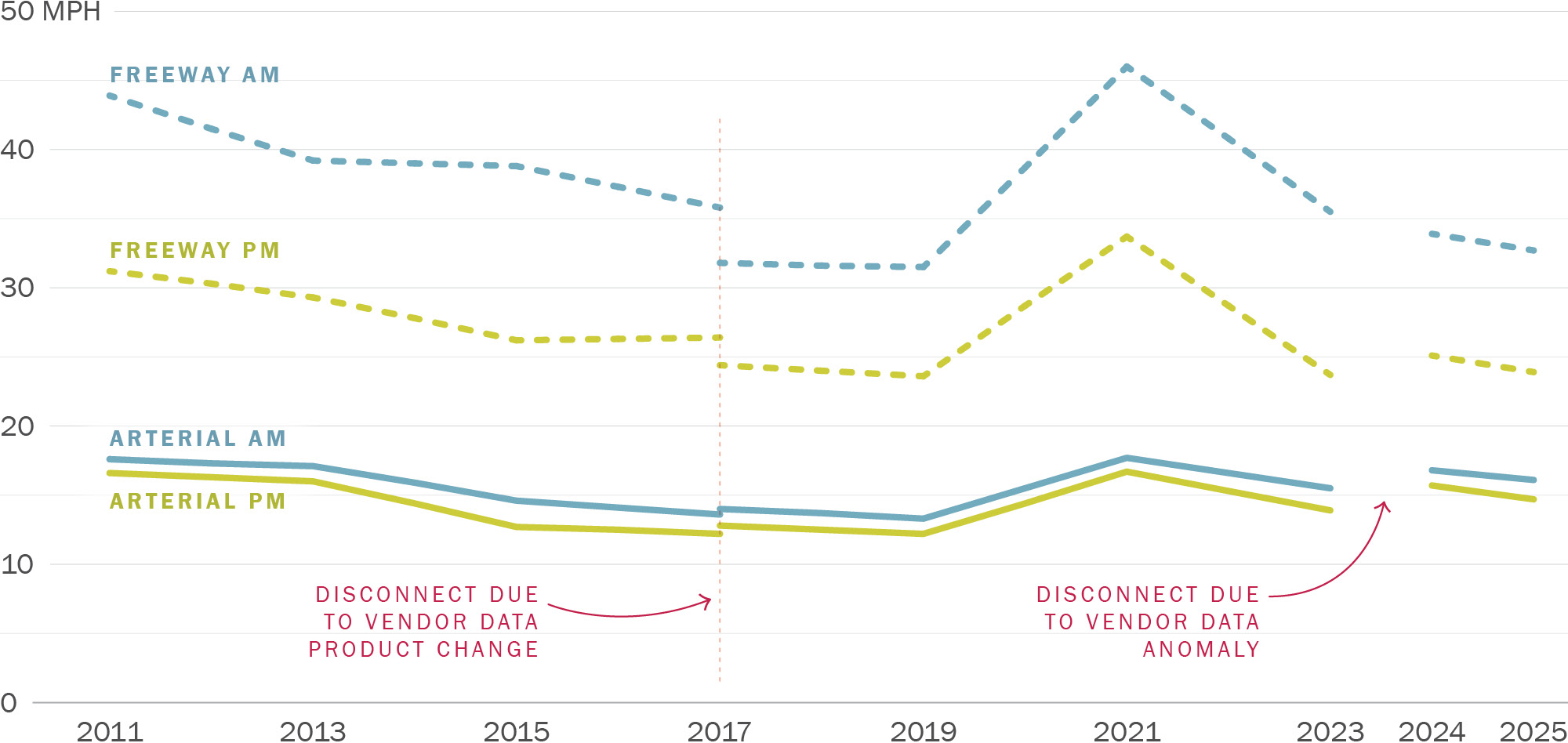

State of San Francisco’s Transportation System

Transportation system performance has begun to stabilize since the COVID-era changes. Arterial and freeway speeds decreased by 4 – 6% between 2024 and 2025. Transit speeds and transit travel time reliability stayed constant between 2023 and 2025. Roadway travel time reliability became better on arterials, but reliability on freeways at peak hours worsened significantly, which may reflect overall increasing peak period congestion near pre-Covid levels, while also having more day-of-week variation in peak period congestion typical of the post-Covid era. Traffic counts on Tuesdays through Thursdays at mid-block locations continued to increase between 2023 and 2025 (+5%), reaching 92% of pre-COVID pandemic (2019) levels. This may indicate that arterial congestion is nearing pre-pandemic levels. The Transportation Authority tracks the ratio of travel speeds by private vehicle vs transit as a primary system performance indicator, reflecting San Francisco’s long-standing Transit First Policy.

Transit ridership is recovering, with Muni, BART, and Caltrain at 72%, 44%, and 54% of 2019 (pre-COVID pandemic) ridership respectively as of Apr/May 2025, and ridership has continued to grow since then. Muni continues to serve more than 95% of San Francisco residents within a five-minute walk of their residence. Moreover, the share of the population within a five-minute walk of a Muni route with a five-minute headway increased to 29% for the AM Peak and to 27% in 2025 for the PM Peak, though this is still lower than the pre-COVID population share within a five-minute walk of a Muni route with a five-minute headway. Multimodal counts conducted at intersections observed sharply rising bicycle counts in the AM Peak (+42%) and PM Peak (+36%) along with more flat pedestrian counts in the AM Peak (+0%) and a modest increase in the PM Peak (+8%). Average monthly micromobility trips have also increased 110% from 2023 to 2025 in data available through September.

The number of property-damage only (PDO) collisions, non-severe injury collisions, and severe injury collisions in San Francisco has remained mostly stable since 2020. However, the number of fatal traffic collisions in 2024 at 42 (of which 23 and 3 involved pedestrians and bikes, respectively) is the highest observed since 2011 (other than 2022 which has the same number of fatal collisions).

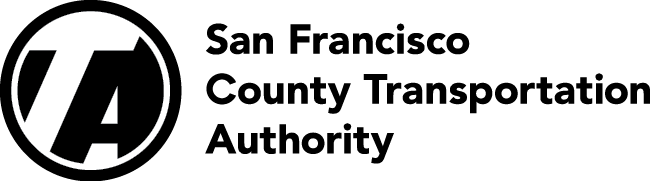

As reported in the Transportation Authority’s Downtown Travel Study (March 2025), while San Francisco continues to be an employment and population hub in the Bay Area, significant changes have occurred in both San Francisco population and employment since the COVID pandemic. San Francisco’s population declined from a peak in 2019 of 882,000 to 814,000 in 2022 due to the COVID pandemic, but its population has been steadily recovering since, reaching 828,000 by 2024. Employment in San Francisco peaked right before the COVID pandemic in 2019 at 764,000, and dropped due to the COVID pandemic between 2019 and 2020. Employment numbers increased to 758,000 in 2022, though there has been a decrease since then to 719,000 in 2024. The COVID pandemic produced profound changes in commuting patterns that affect the transportation system performance metrics reported in this document. In 2019, only 7% of employed San Francisco residents reported regularly working from home, but during the peak of the COVID pandemic in 2021, this share increased to 46%, before declining in 2023 to 24% of employed residents working from home.ACS One-Year Supplemental Estimates, Table K200801

Note: Population and employment estimates are as of July 1 of each year

Population Source: US Census Population and Housing Unit;

Employment Source: California Employment Development Department Current Employment Statistics

Download chart data (CSV)

Roadway Monitoring Results

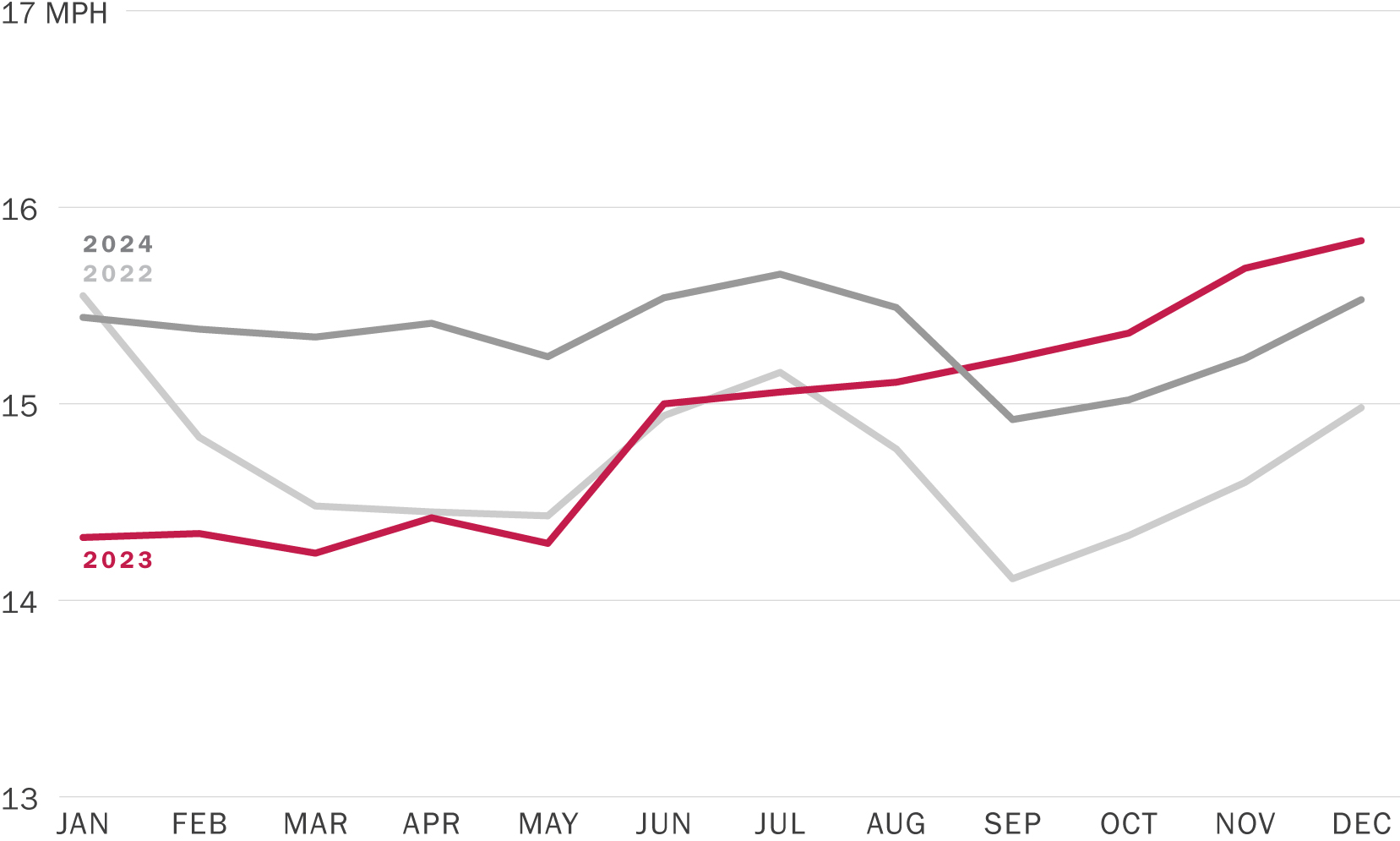

Fall 2023 Data Anomaly and Change to Methodology

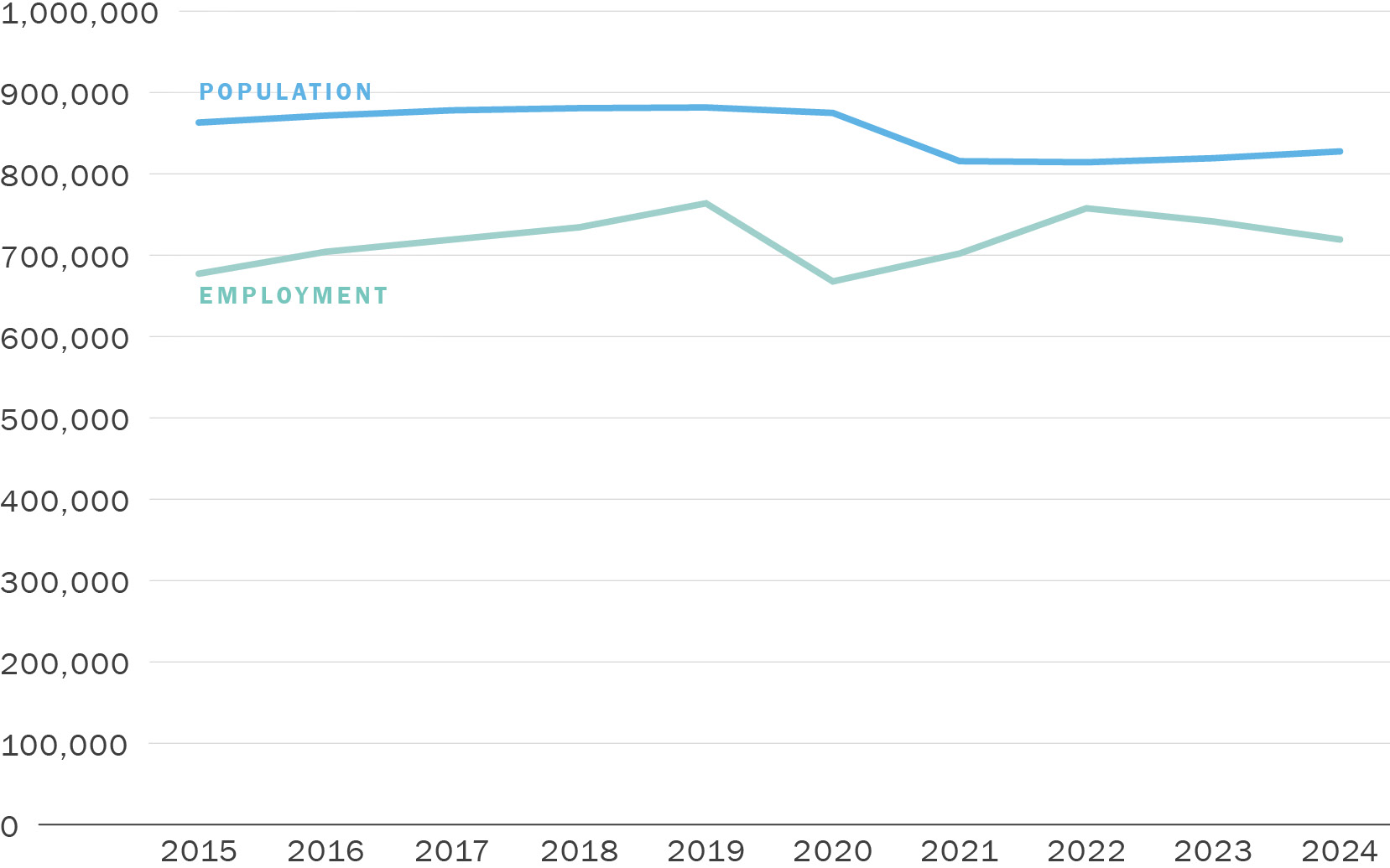

Traffic speeds vary seasonally, with lower speeds in the spring and fall, and higher speeds in the summer and winter during holidays and school closures. The CMP accounts for this seasonality by monitoring speeds in the same months, April and May, of each year. Speeds during 2020 and 2021 followed unique patterns due to the Covid 19 pandemic, but typical seasonality was evident again in 2022. From 2022 to 2025 so far, each year has exhibited normal seasonal trends. However, in August and September of 2023, when speeds typically decline from summer highs, INRIX data showed speeds continuing to increase. Staff could not identify any events that would explain a significant two-month long deviation in typical seasonal speed trends and believe there is an error in the underlying data or change in data processing methods, although INRIX has not confirmed this. After this unexplained increase in speeds data resumed typical seasonal patterns, although at elevated speeds. This resulted in higher peak period traffic speeds in 2025 than in 2023, which is an unintuitive trend that is not supported by contemporaneous arterial traffic counts in 2023 and 2025. As a result, the following analysis compares 2025 data to 2024 rather than data from the previous 2023 cycle, as would be typical.

Download chart data (CSV)

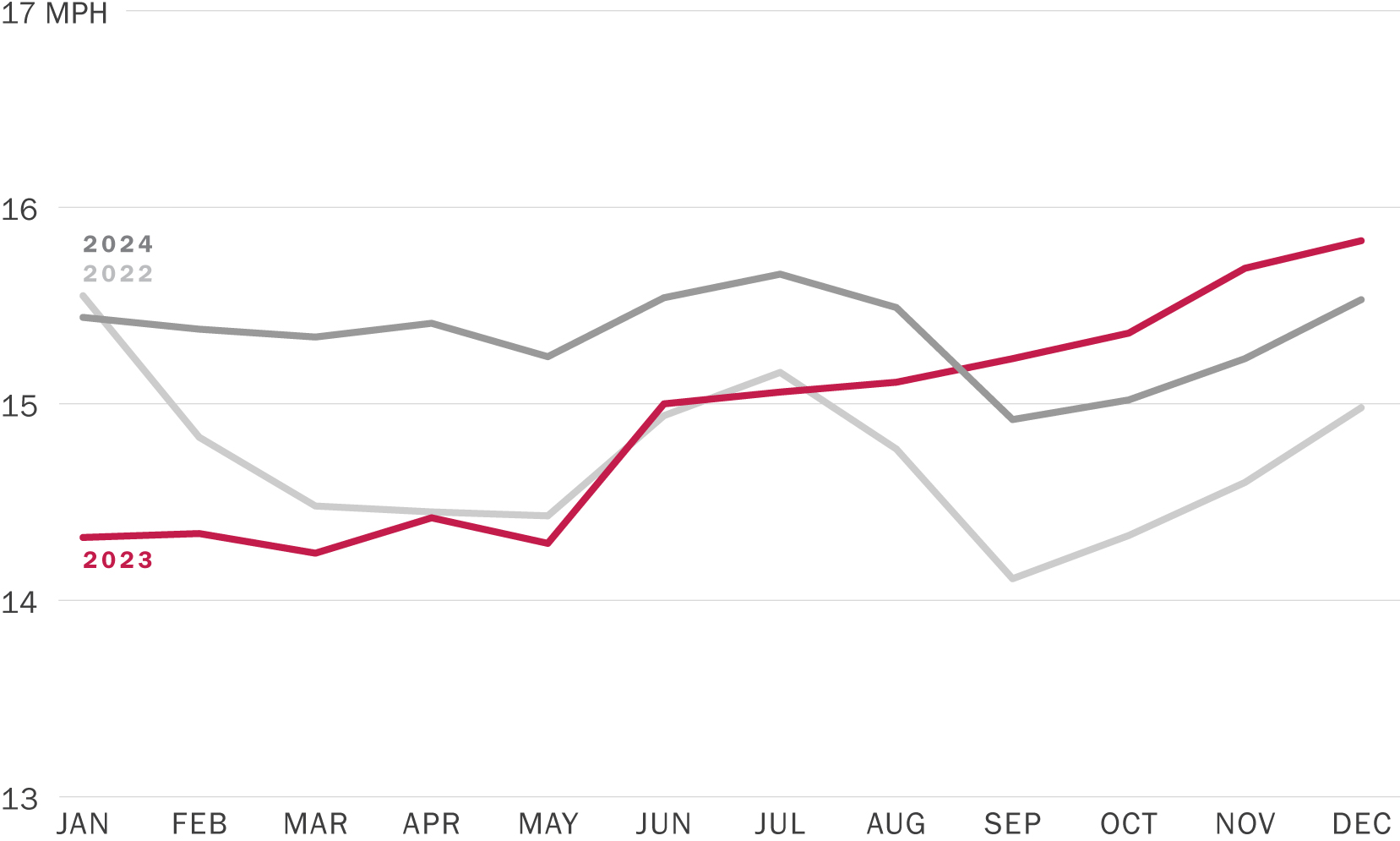

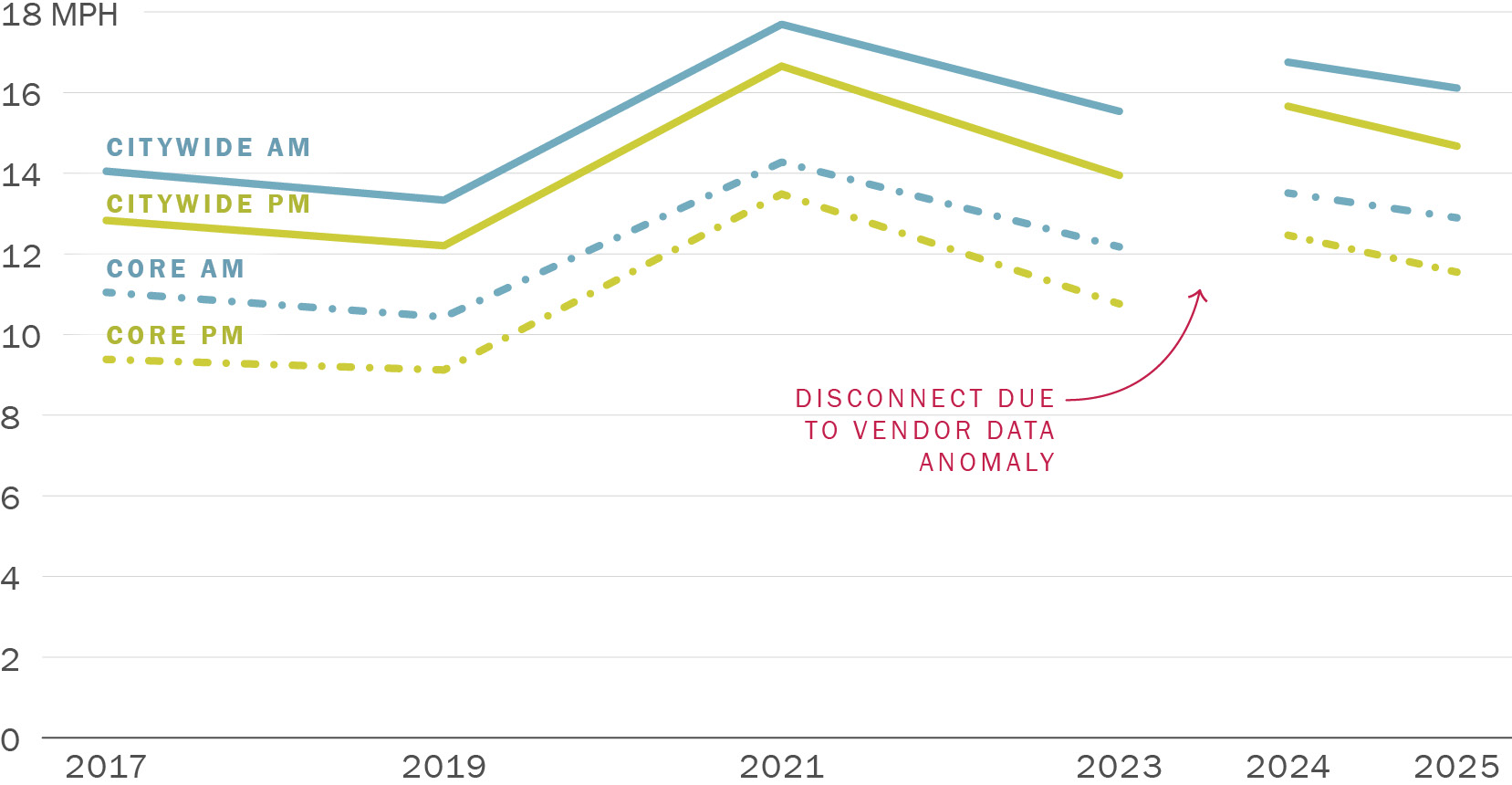

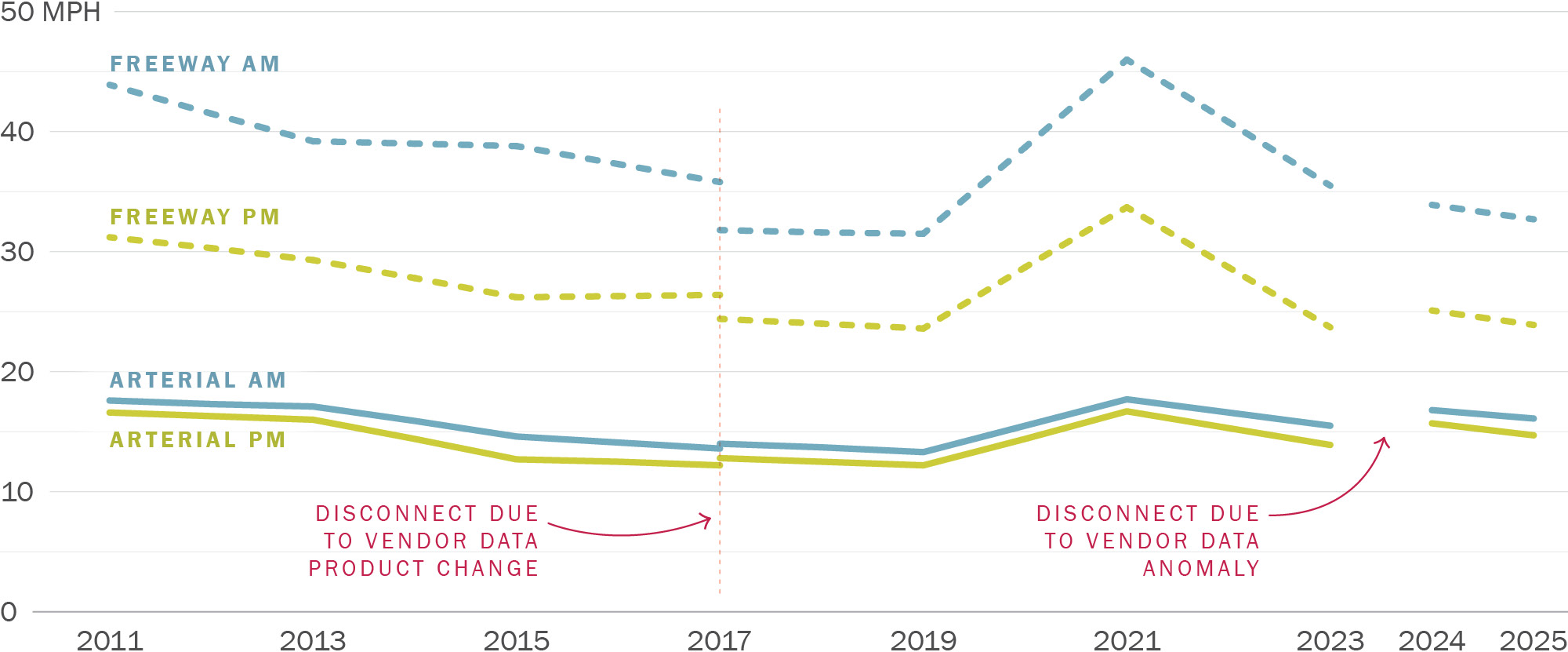

Roadway Speeds

In general, roadway speeds are lower during the PM Peak than in the AM Peak, conforming to long-time historical trends. Roadway speeds increased in 2021 during the COVID pandemic, then decreased between 2021 and 2023 as people began to return to pre-COVID pandemic activity levels. The trend in speeds from 2023 to 2024 is unknown due to the anomaly described above. From 2024 to 2025 Freeway AM Peak speeds decreased by 4% and PM Peak speeds decreased 6%. Arterial speeds decreased by 4% in both the AM Peak and PM Peak between 2024 and 2025 (Figure 0-3).

Note: data collected April – May each year

Download chart data (CSV)

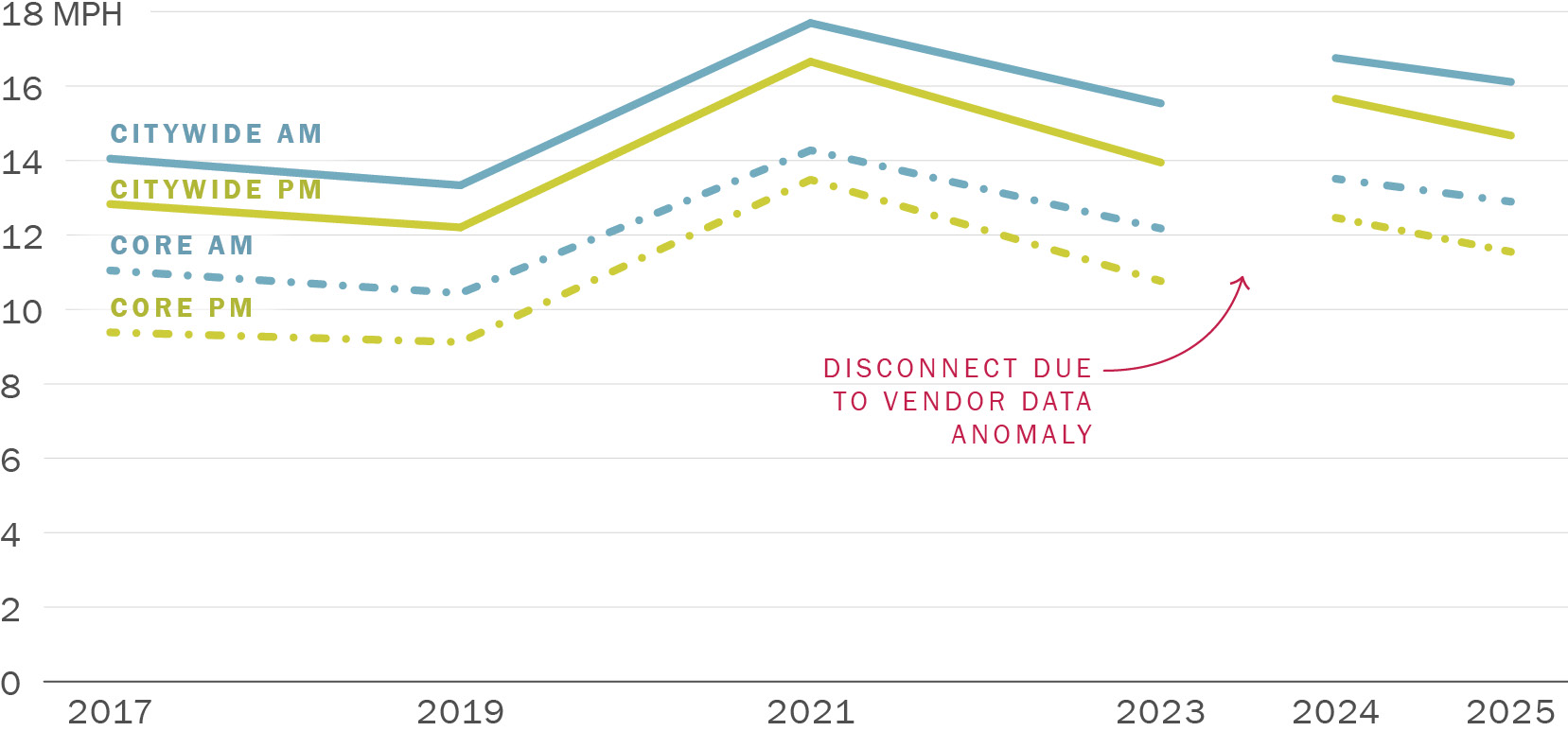

Arterial roadway speeds in the downtown core are historically lower than citywide average arterial speeds. Between 2024 and 2025, arterial speeds in the downtown core declined by 6% in the AM Peak and 7% in the PM Peak, a faster rate of decline than citywide arterial speeds (Figure 4-3)

Note: data collected April – May each year

Downtown Core in this figure is defined to include streets east of Franklin/Gough Streets, and north of the Central Freeway and Mission Creek. It also includes the streets immediately surrounding the Octavia Boulevard entrance/exit of the Central Freeway

Download chart data (CSV)

Roadway Level of Service (LOS)

The CMP legislation defines roadway performance primarily by using the LOS traffic engineering concept to evaluate the operating conditions on a roadway. LOS describes operating conditions on a scale of A to F, with “A” describing free flow, and “F” describing bumper-to-bumper conditions.

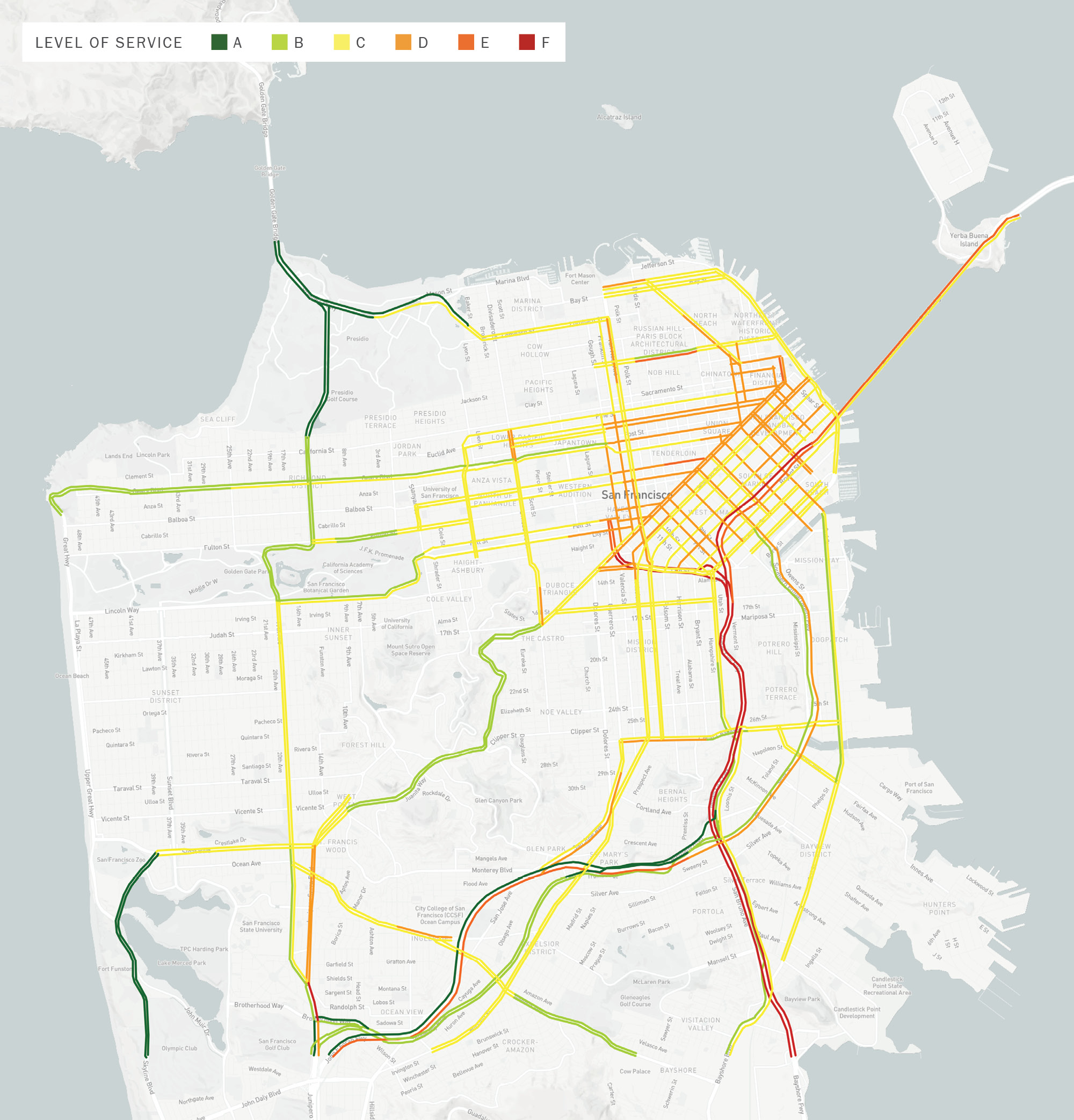

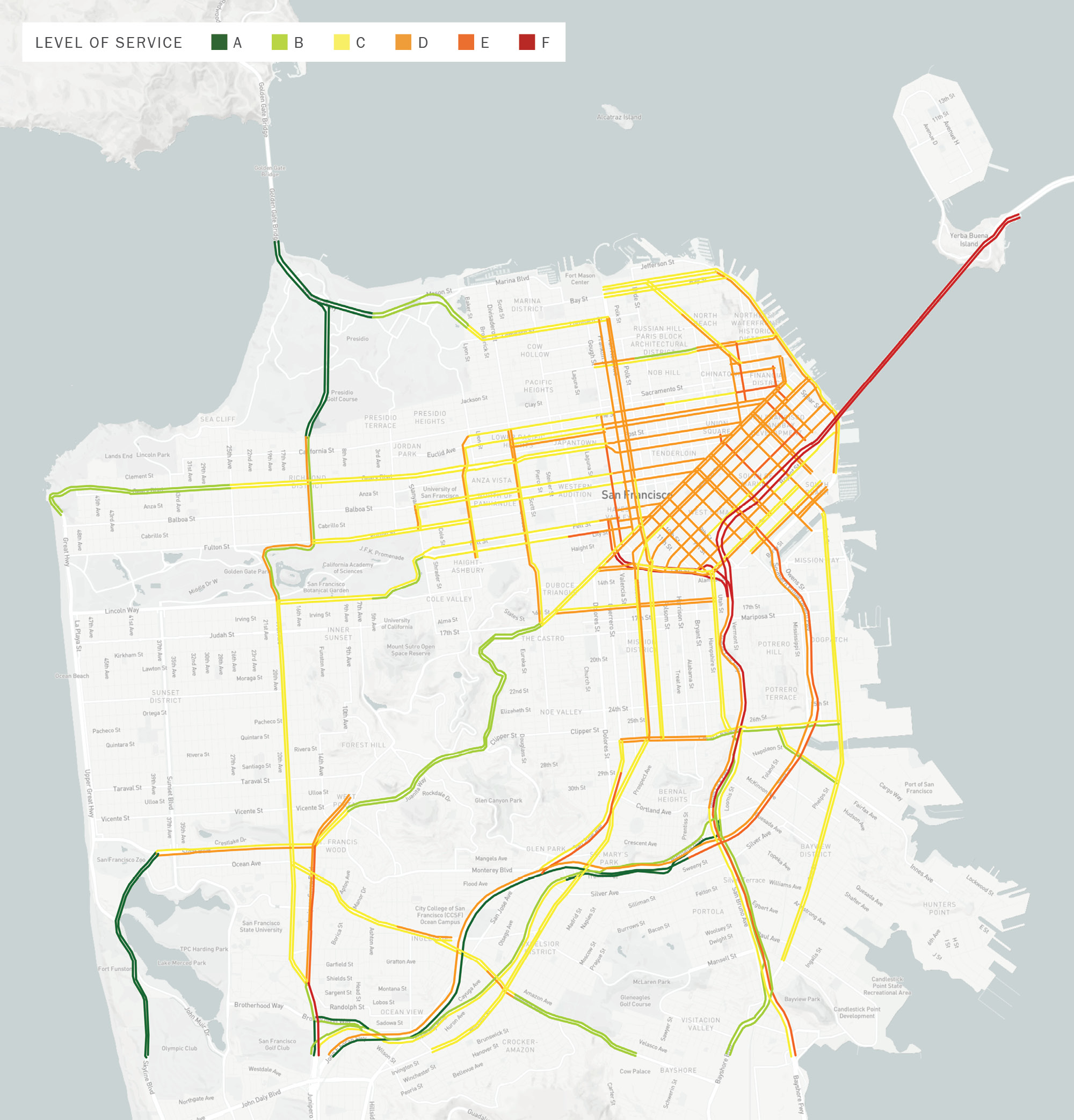

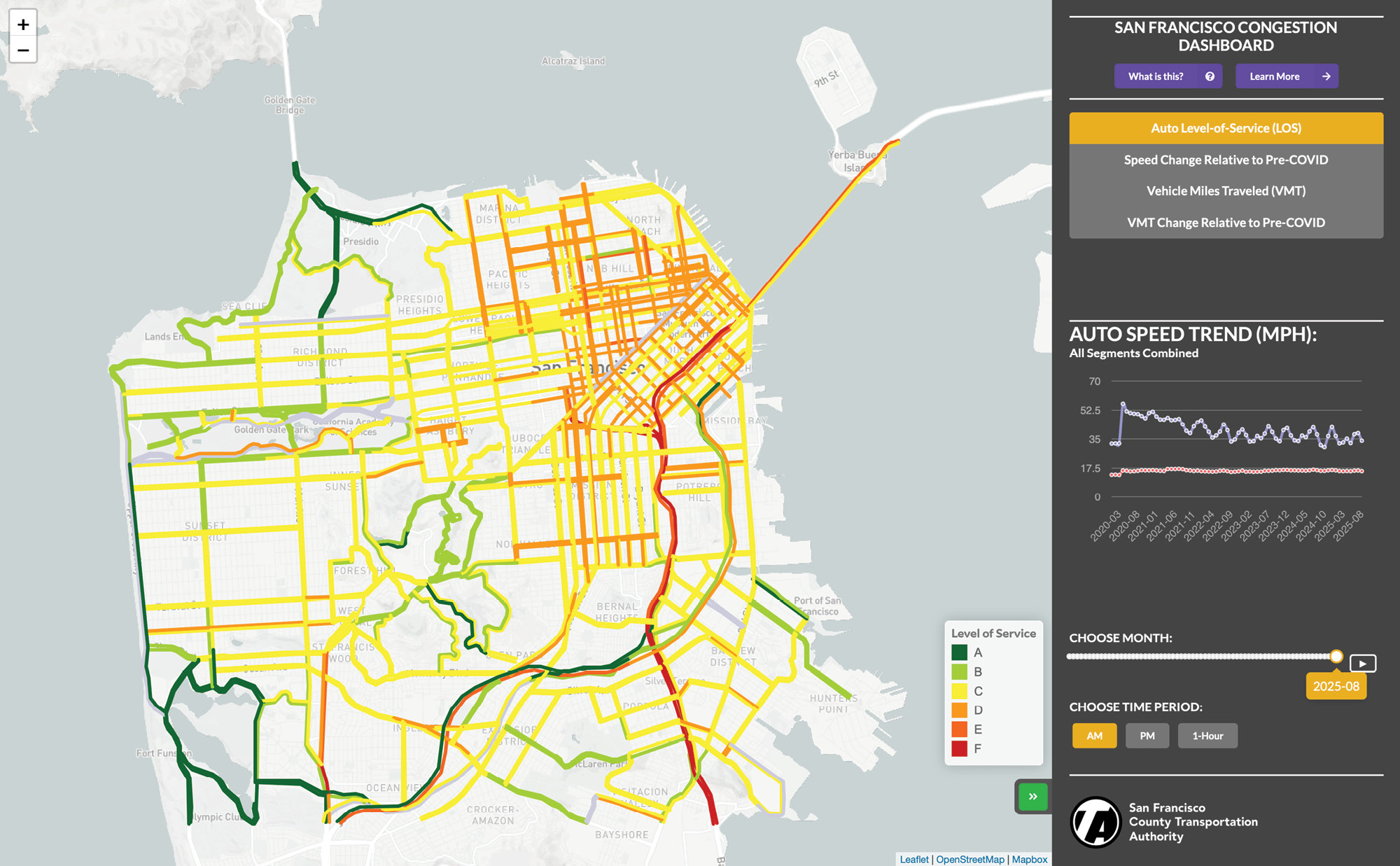

Figure 0-5 shows PM Peak LOS in 2025. Freeways approaching and traversing the downtown core are congested, with LOS ranging from D and F. The southern leg of US-101 and I-280, further from the downtown core, are less congested, with LOS ranging from A to D. Arterials in downtown are nearly uniformly LOS D, while arterials outside of the core perform better and have more variability, ranging from A to D. The AM Peak shows similar trends. As noted in the Downtown Travel Study, this profile of traffic congestion lies within a context of a fluid downtown recovery. An interactive version of this map that allows users to view historical trends for the City overall, as well as for all the individual CMP segments, can be found at cmp.sfcta.org.

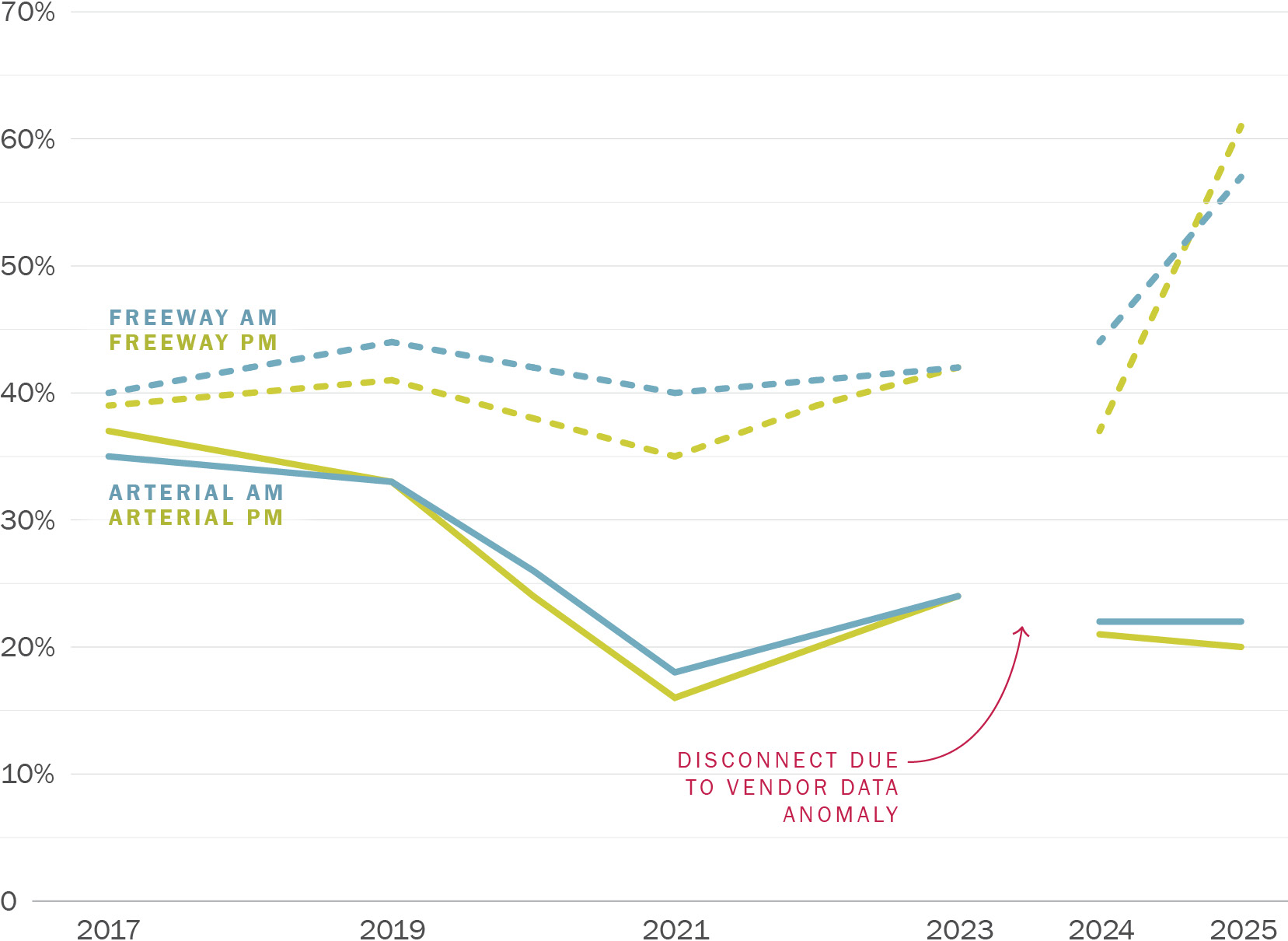

Roadway Travel Time Reliability

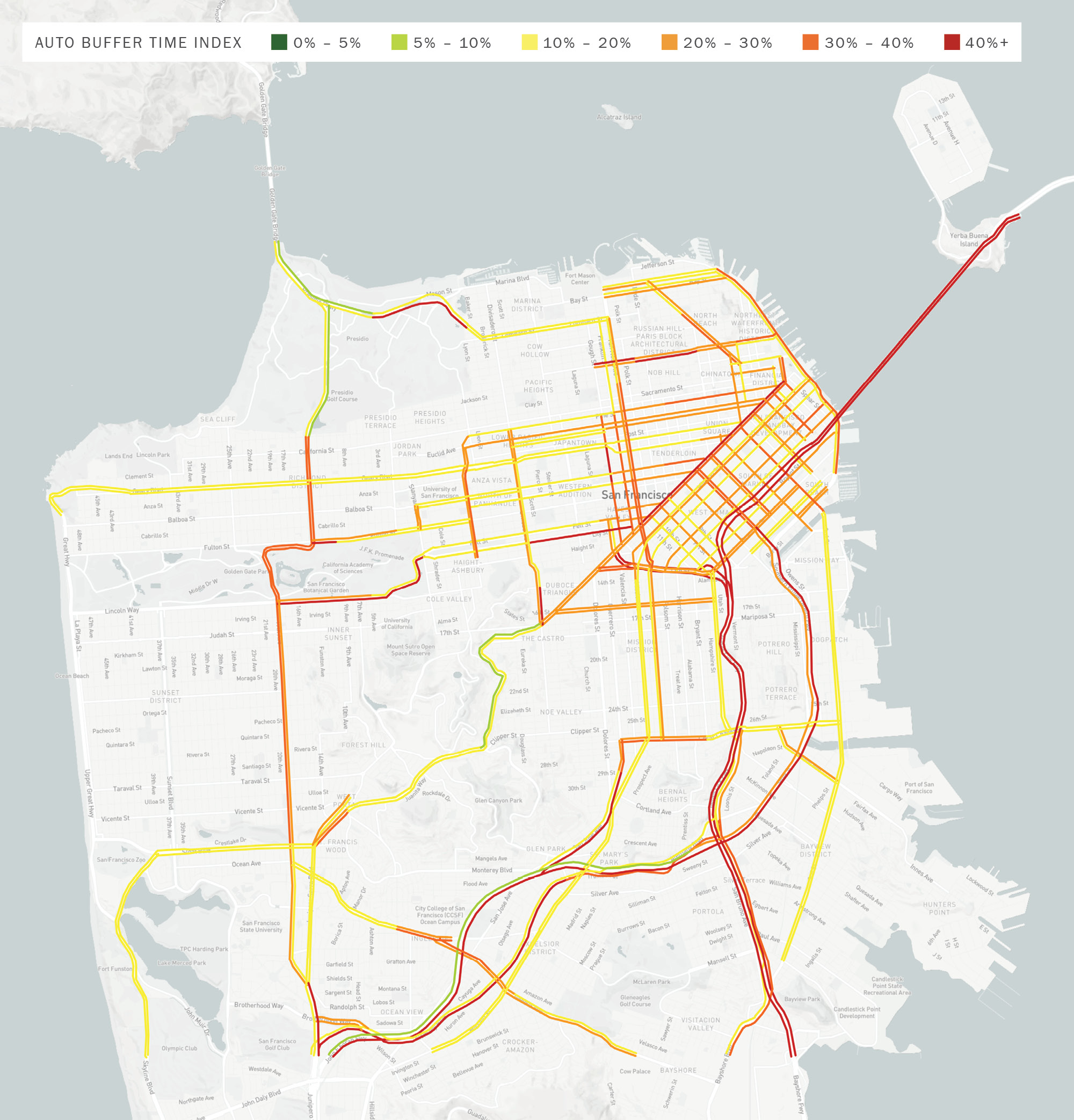

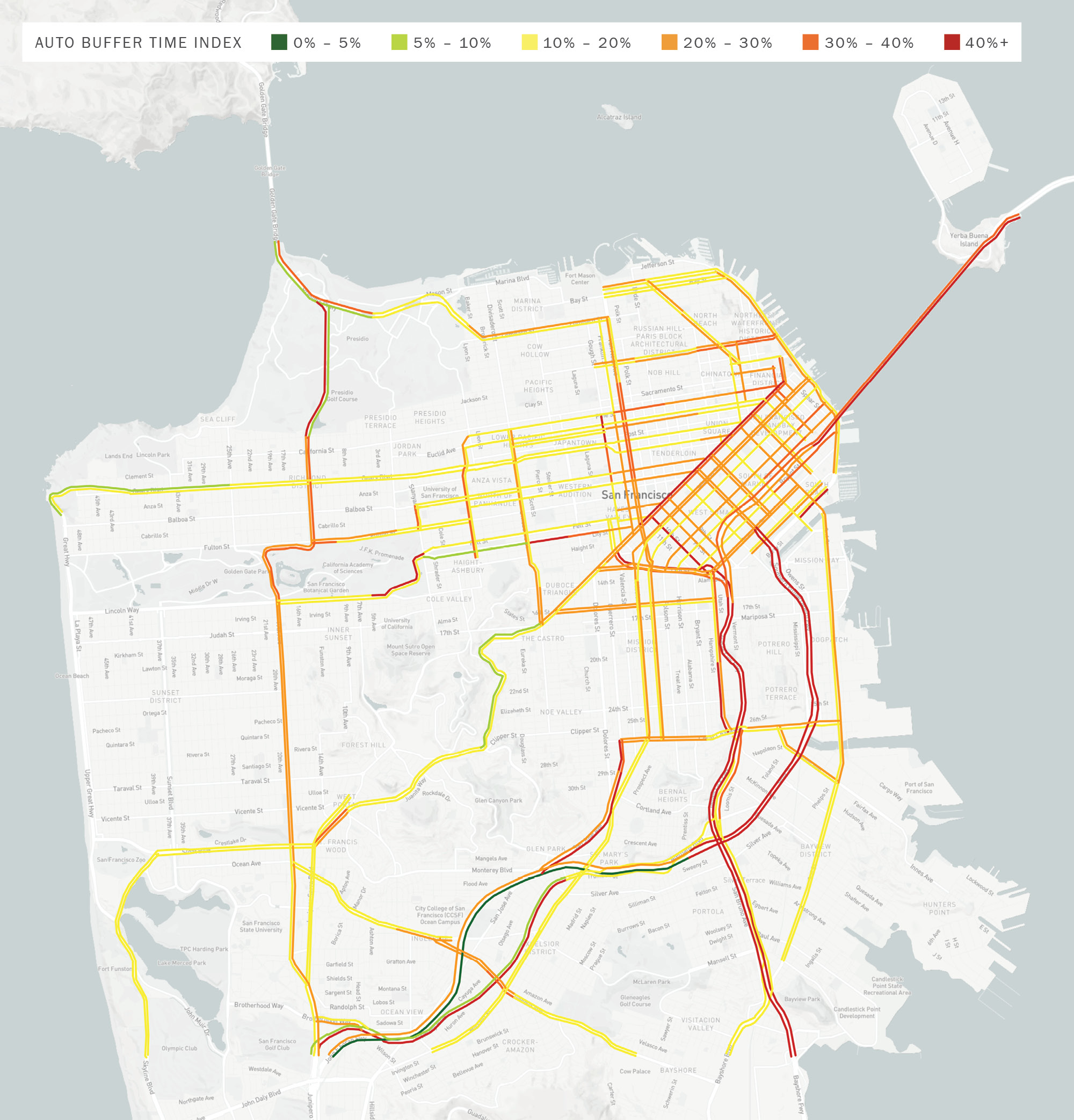

While the average travel speeds and LOS provide useful insights into congestion, they do not capture a critical aspect of peoples’ perception of congestion, which is the reliability of travel times. For example, a traveler is likely to perceive the congestion on a roadway where the travel is always 15 minutes differently that they perceive the congestion on a roadway where half the time the travel time is 5 minutes and the other half the time the travel time is 25 minutes. The unreliability of the travel time on this second roadway is onerous because it forces travelers to change their schedule so as to ensure that they aren’t late to their destinations.

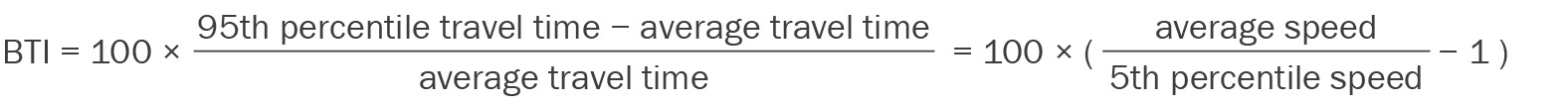

The Buffer Time Index (BTI) is a measure of the unreliability of vehicular travel time, and is calculated as the percent of average additional travel time that the travelers need to budget so that they have a 95% chance of arriving on time. In other words, it is the extra time needed if one does not want to be late more than once a month, and a lower value of BTI indicates higher reliability (see below for a parallel measure for transit travel). For example, a BTI of 20% for a 10 minute trip requires a traveler to budget an extra 2 minutes to not be late more than once a month.

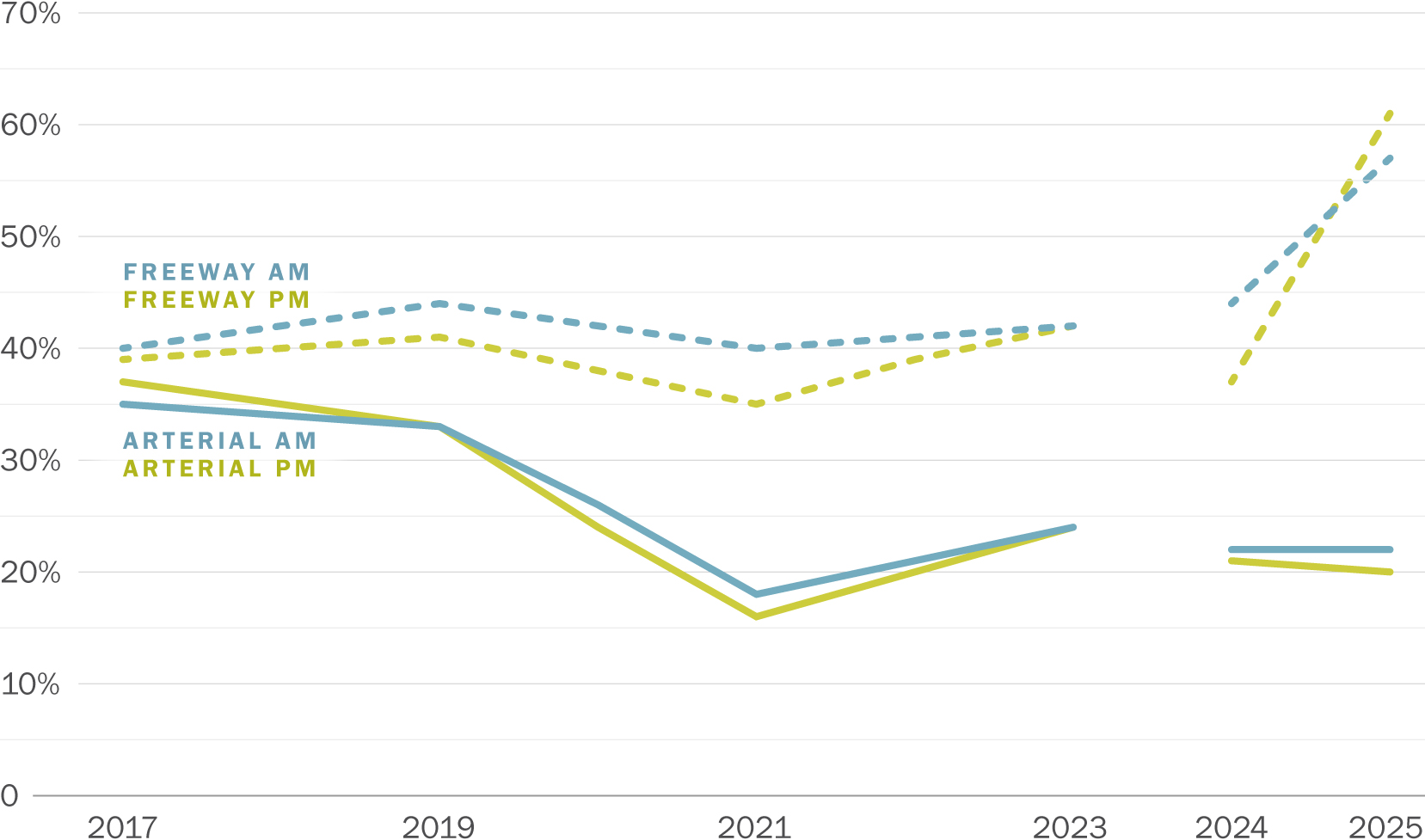

Between 2024 and 2025 reliability remained flat on CMP network arterials, with the BTI remaining at 22% in the AM Peak and decreasing 21% to 20% in the PM Peak (a slight improvement in reliability). In contrast, freeway travel time reliability worsened significantly over the same period from 44% to 57% in the AM Peak and from 37% to 61% in the PM Peak (Figure 0-6), indicating a rising need to manage freeway demand (see San Francisco Freeway Management Study, underway).

Note: data collected April – May each year

Download chart data (CSV)

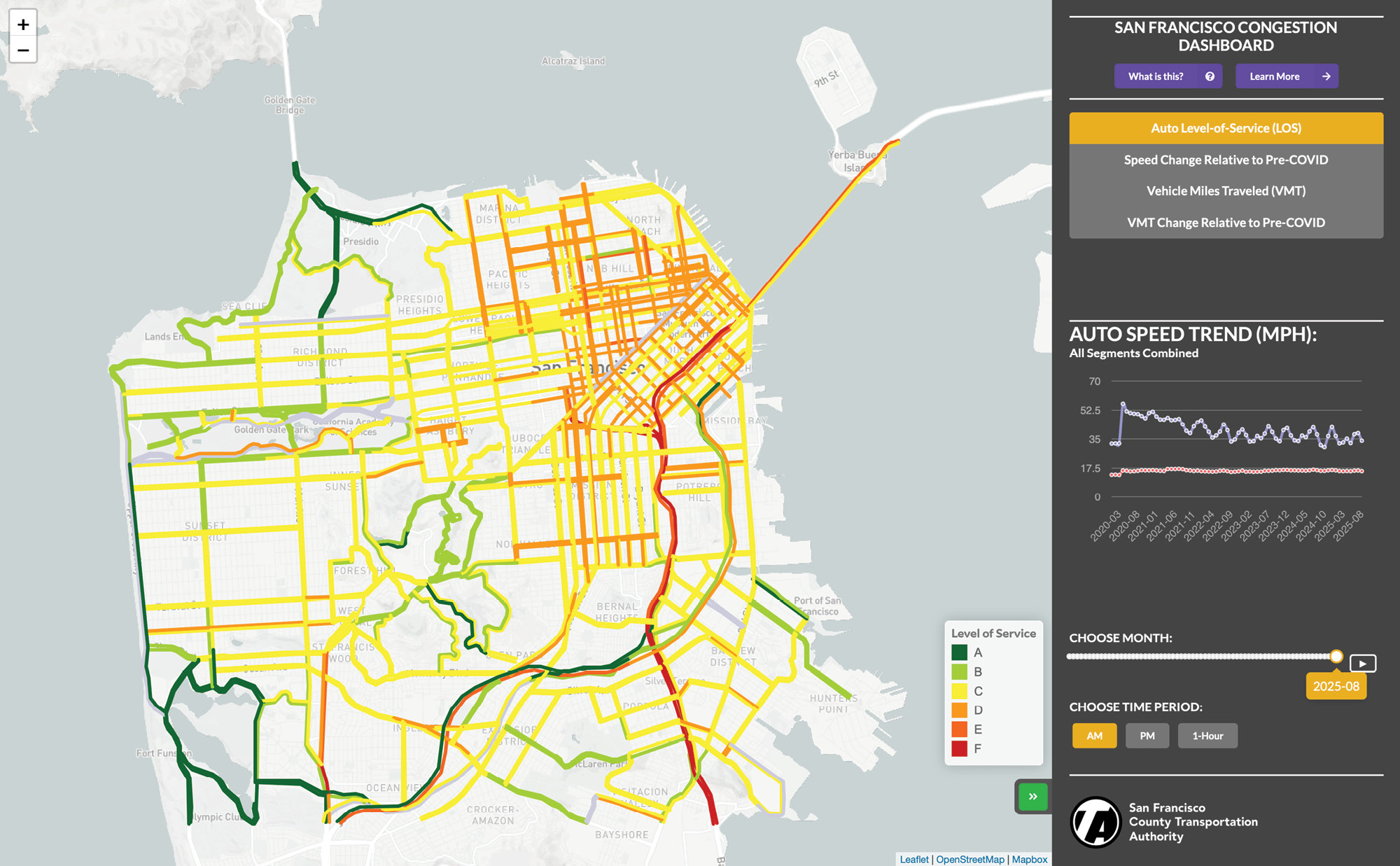

San Francisco Congestion Dashboard

The Transportation Authority maintains the San Francisco Congestion Dashboard (congestion.sfcta.org), shown in Figure 0-7. This tool reports many of the same roadway performance metrics as reported the CMP congestion visualization, but with a much greater frequency (monthly instead of biennially), for a larger set of roadway segments, and at an hourly level as well as for the AM Peak and PM Peak periods starting in January 2020.

Transit Monitoring Results

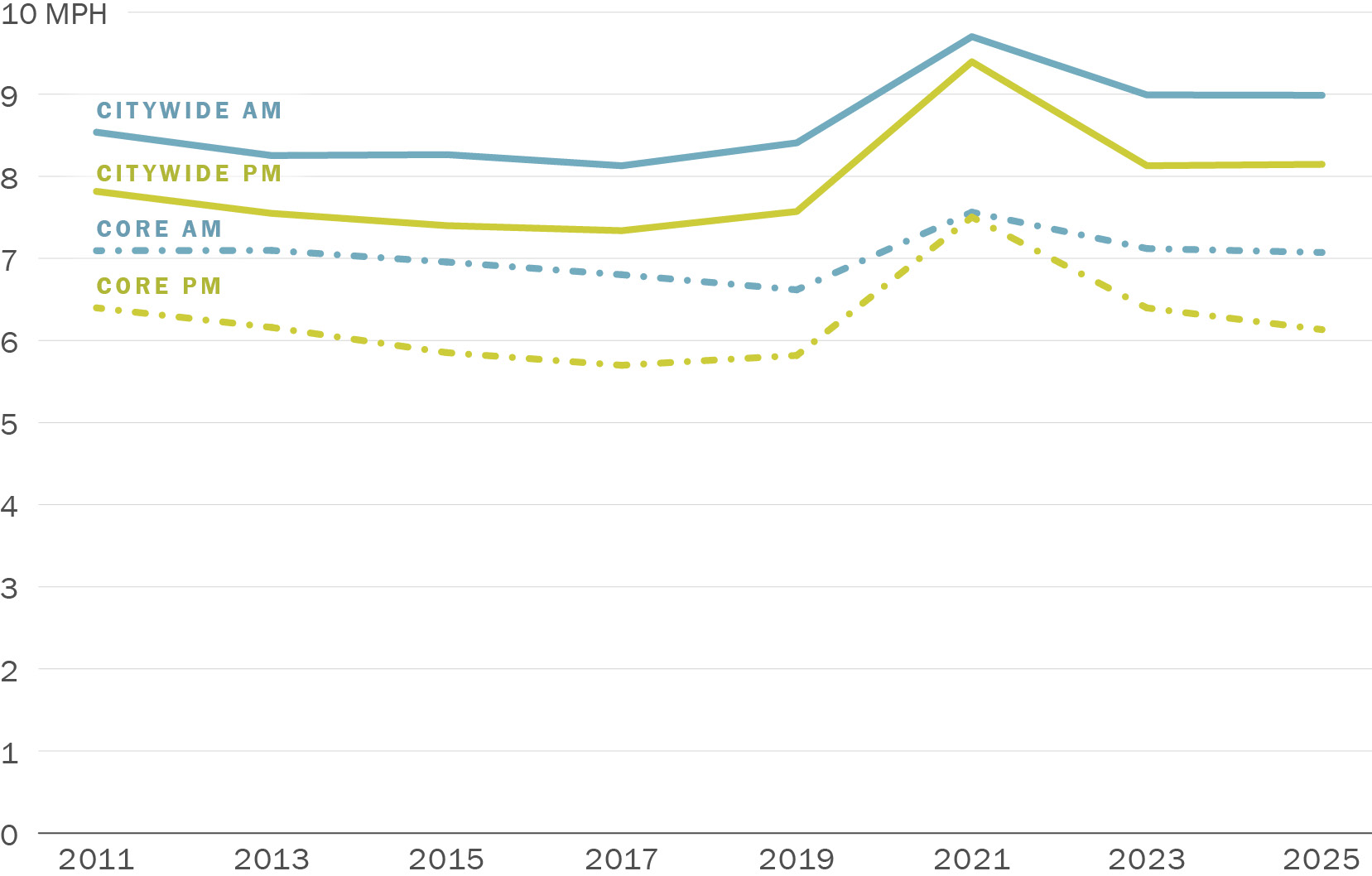

Transit Speeds (Muni bus)

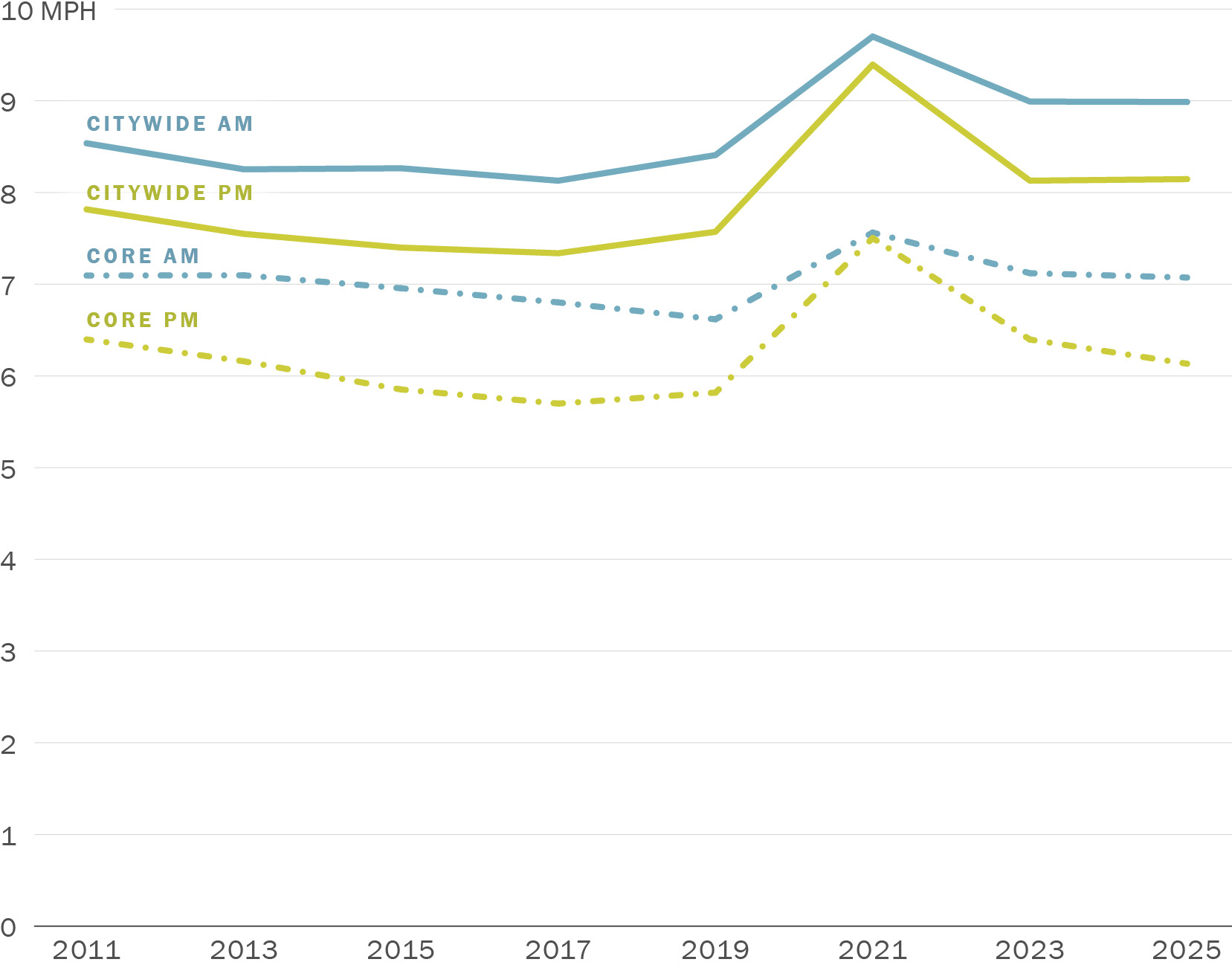

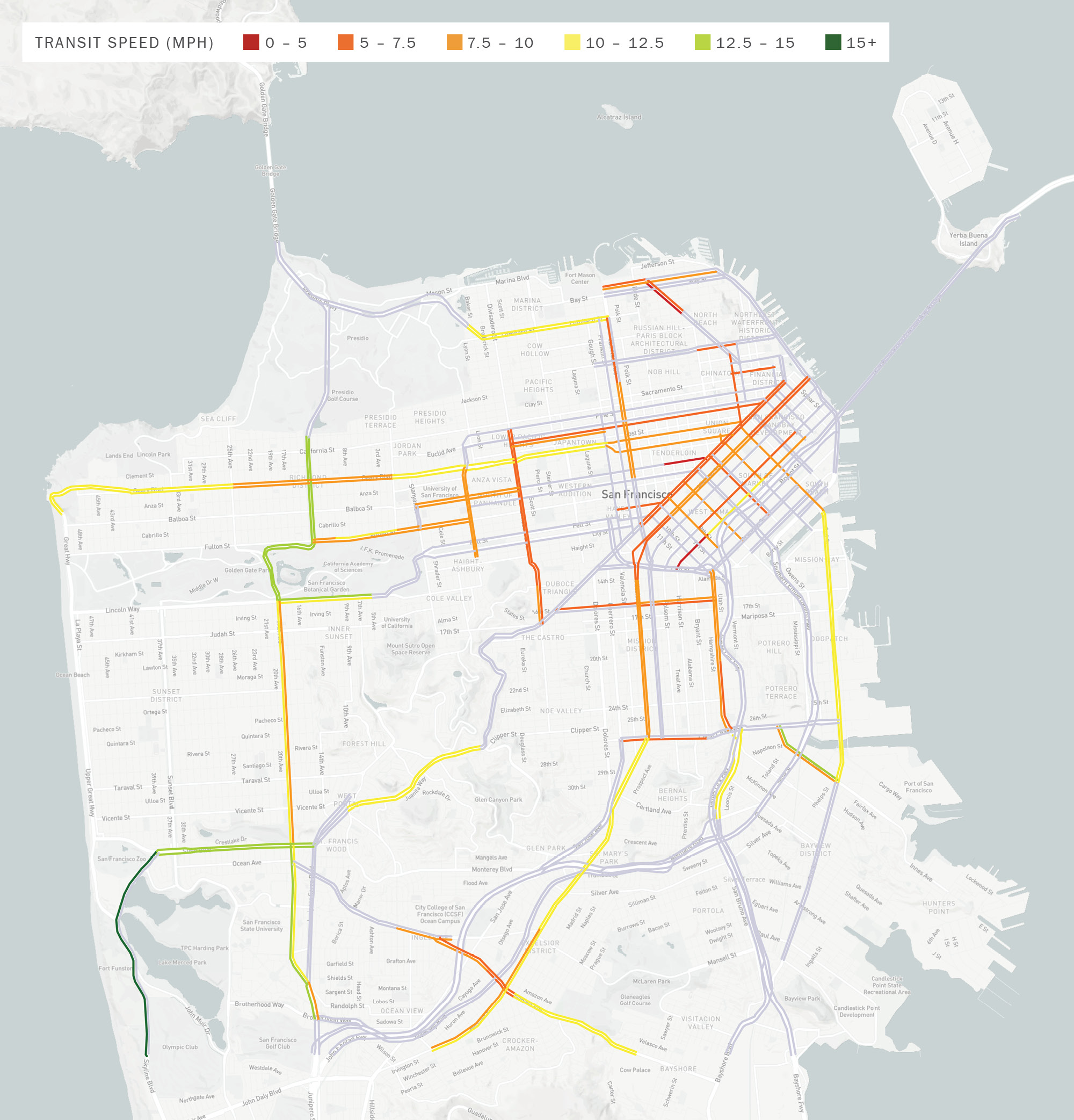

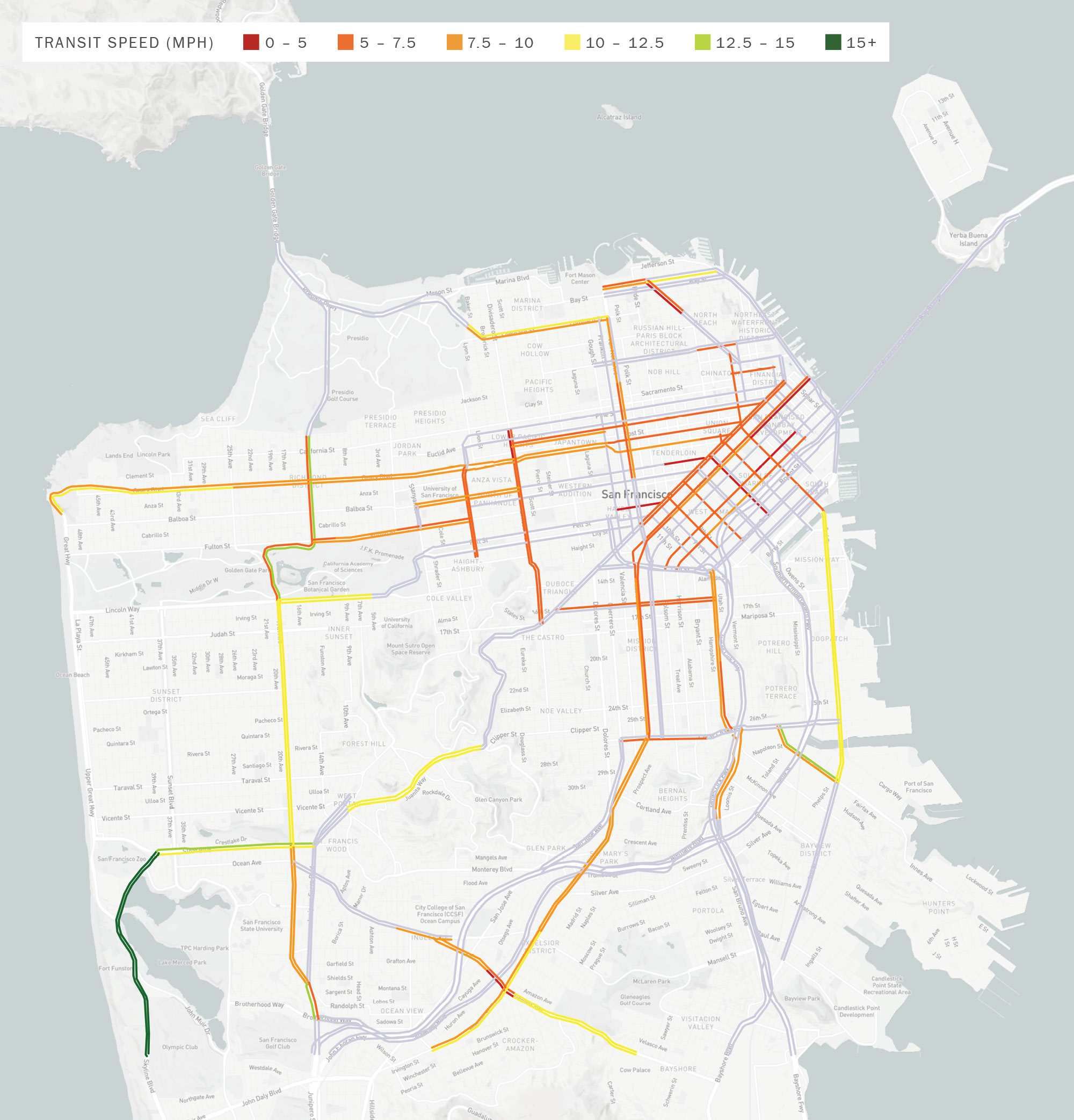

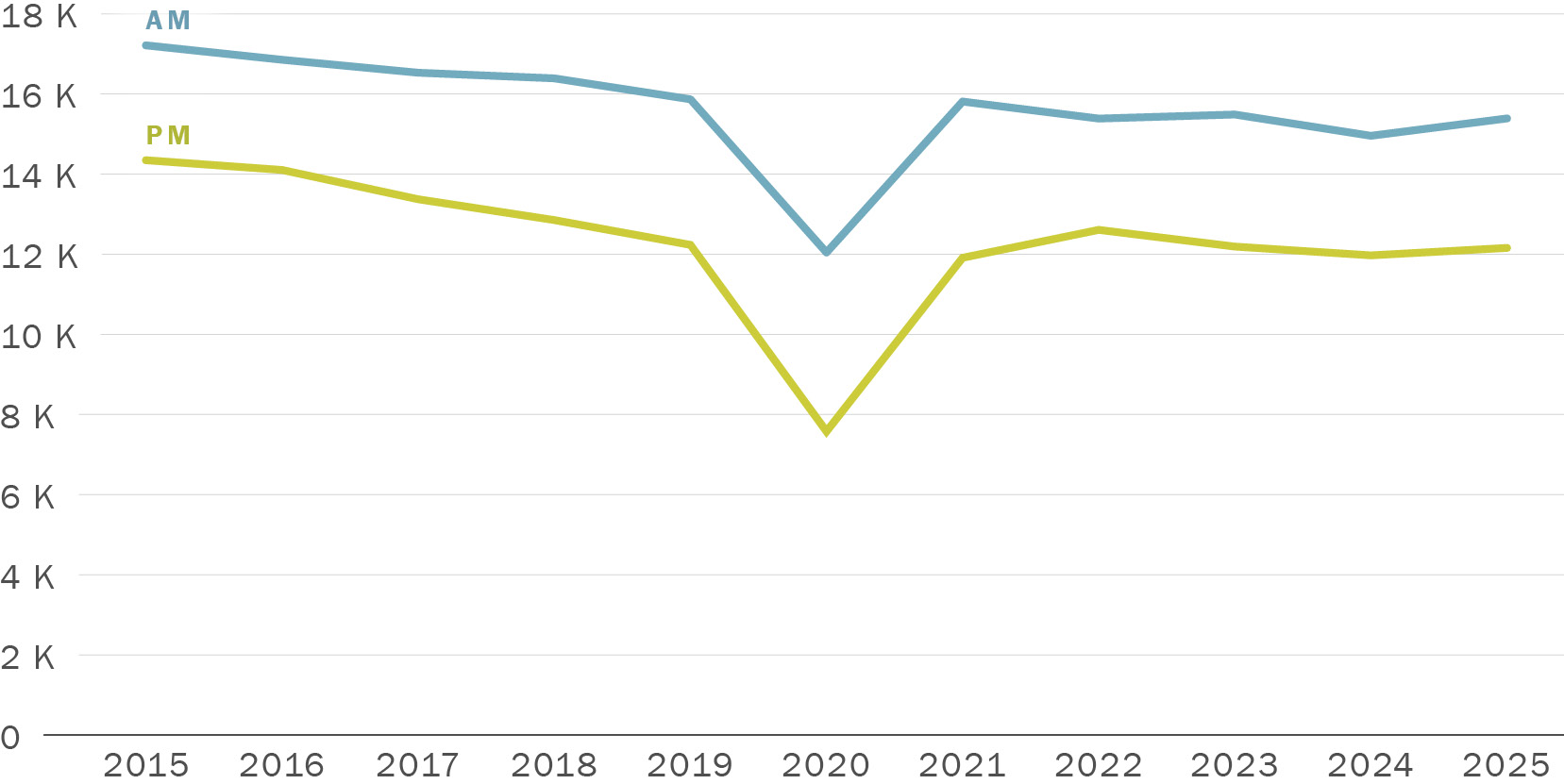

Average transit travel speeds on the CMP network for both the AM Peak and PM Peak stayed constant between 2023 and 2025, a positive outcome, given the rise in vehicle traffic and multimodal activity over this period. Transit speeds in 2025 are still higher than that during pre-COVID (Figure 0-8).

Note: Downtown Core in this figure is defined to include streets east of Franklin/Gough Streets, and north of the Central Freeway and Mission Creek. It also includes the streets immediately surrounding the Octavia Boulevard entrance/exit of the Central Freeway

Download chart data (CSV)

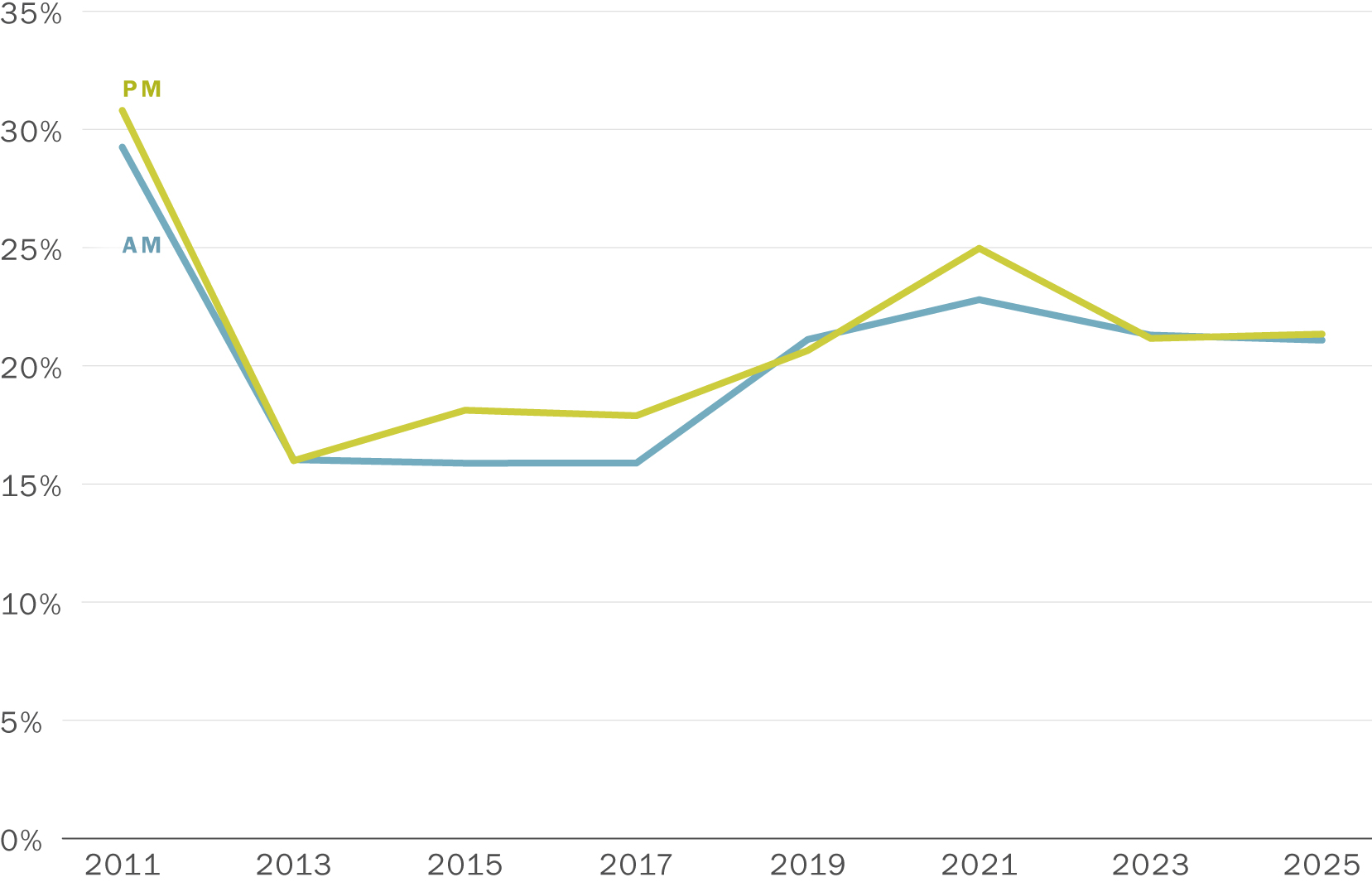

Transit Speed Reliability (Muni bus)

Transit (Muni bus) speed information is also used to calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) of speed as a measure of transit speed reliability. The coefficient of variation is calculated by dividing the standard deviation of the speed by the average speed, thereby normalizing the results to compare relative variability between faster and slower segments. The CV is expressed as a percentage of the mean speed. A lower percentage indicates more reliable transit speeds.

Transit reliability has stabilized (i.e. variability stayed the same) since 2023, staying at the same levels (21%) observed in 2019 and 2023 for both the AM Peak and PM Peak (Figure 0-9). With the average transit speeds in 2025 at 9.0 MPH (AM Peak) and 8.1 MPH (PM Peak), a CV of 21% means that approximately 70% of the time, a 3 mile transit trip would take between 15.8 and 24.2 minutes for the AM Peak, and between 17.6 and 26.9 minutes for the PM Peak. As with transit travel times, this is a positive trend and may reflect benefits from a variety of transit priority investments and traffic management strategies that were implemented during this time.

Download chart data (CSV)

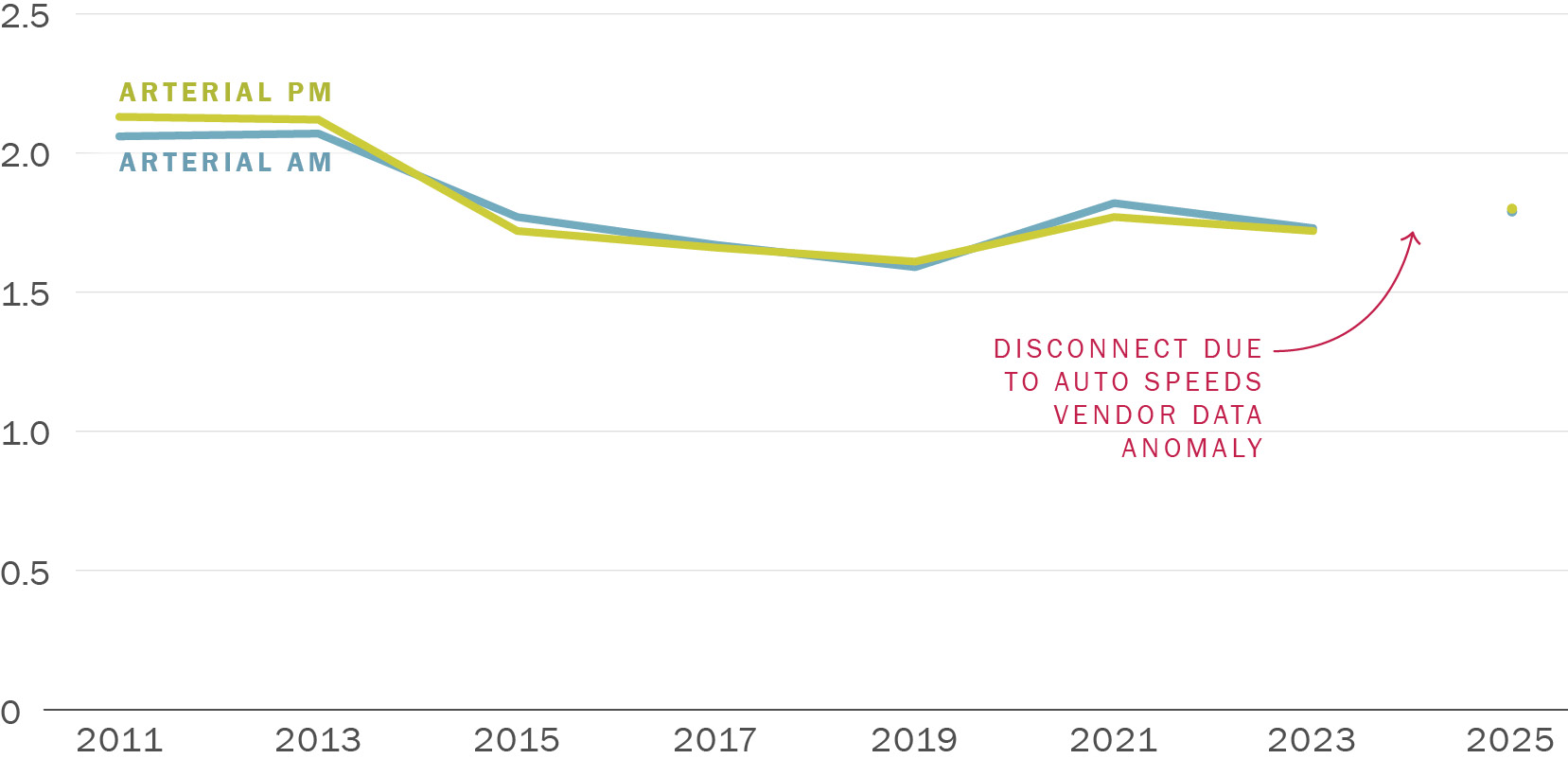

Auto-Transit Speed Ratio

In order to assess the competitiveness of transit with driving, the ratio of auto to transit speeds is calculated by comparing auto to transit speeds on the portions of the CMP network for which Muni bus data is available. A ratio of 2 would indicate that, for a particular segment, auto speeds are twice as fast as transit speeds. The ratio had been improving between 2013 and 2019, worsened during the COVID pandemic and has been hovering around 1.7 – 1.8 since 2021. In 2025, the auto-to-transit speed ratio was 1.8 in the AM Peak and PM Peak periods. Due to the Fall 2023 data anomaly, the auto-to-transit speed ratio for 2025 cannot be directly compared to 2023.

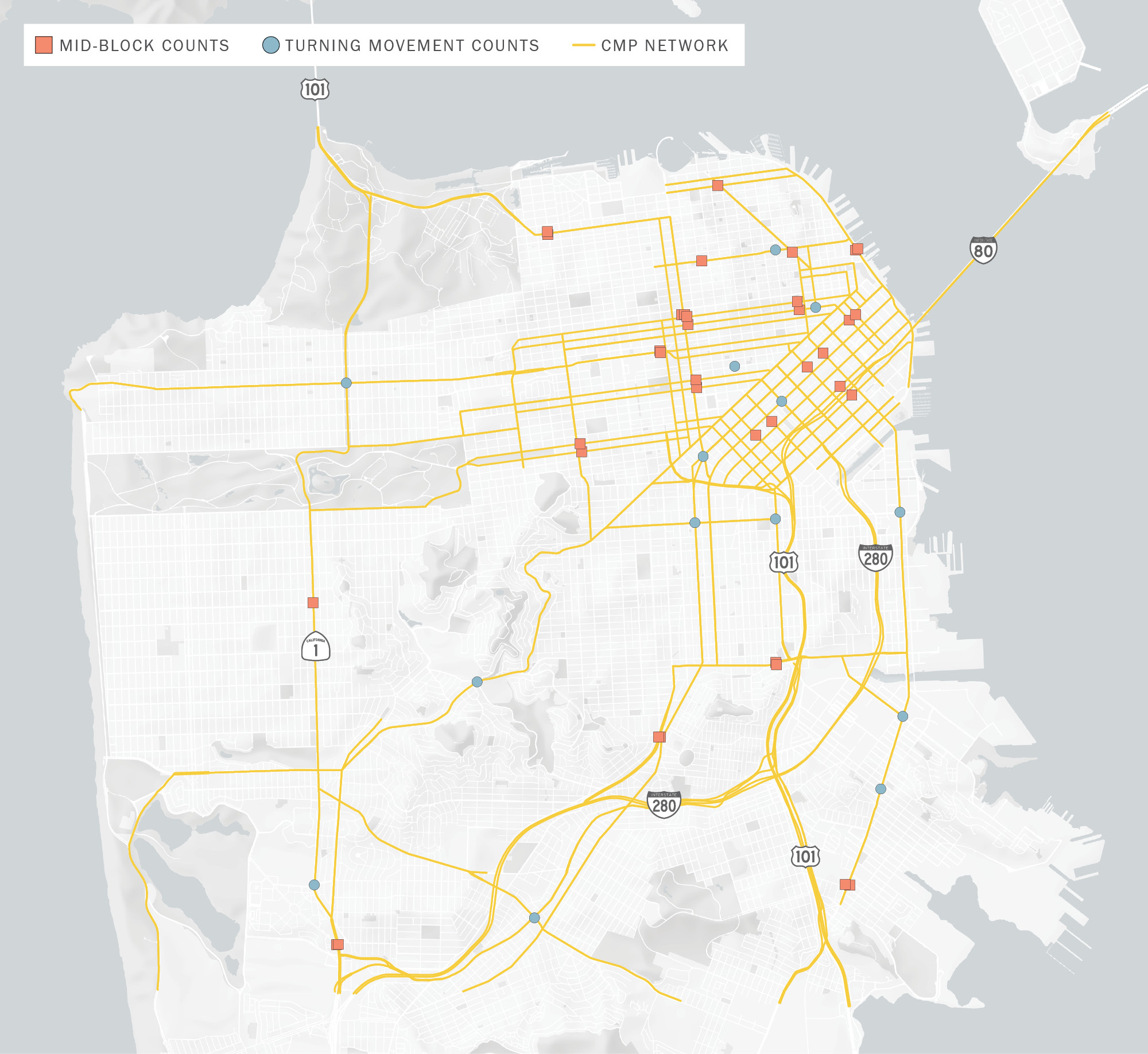

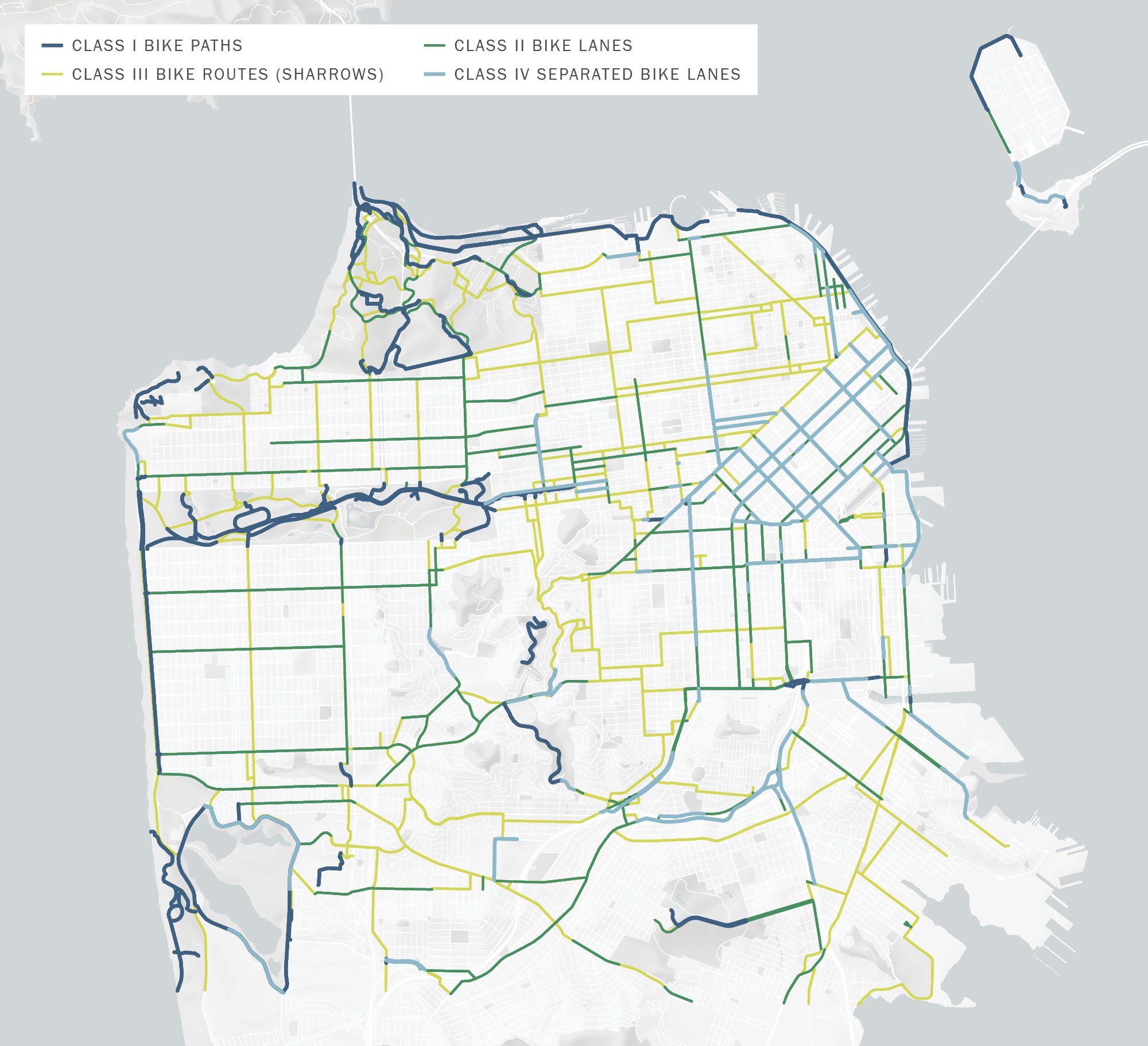

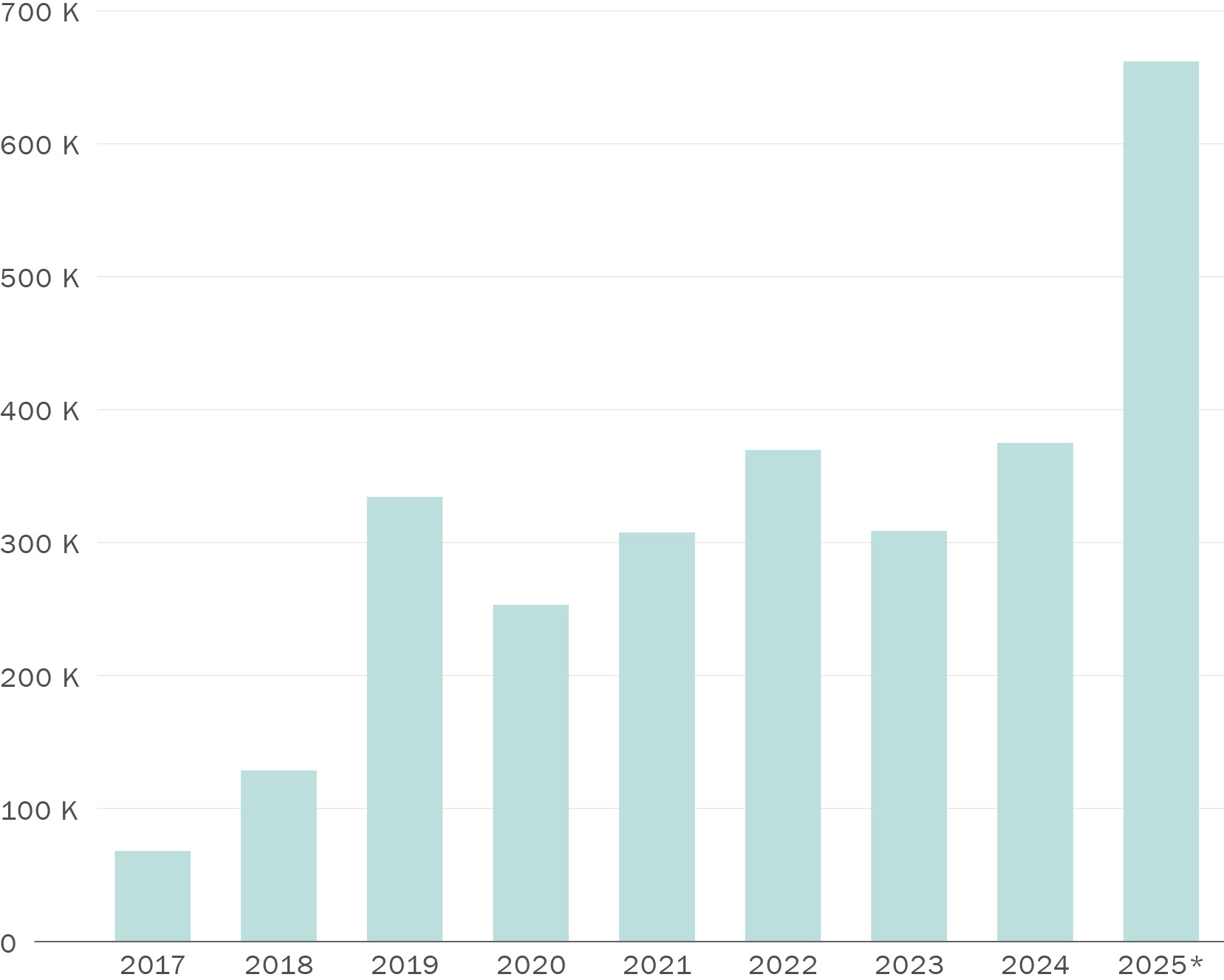

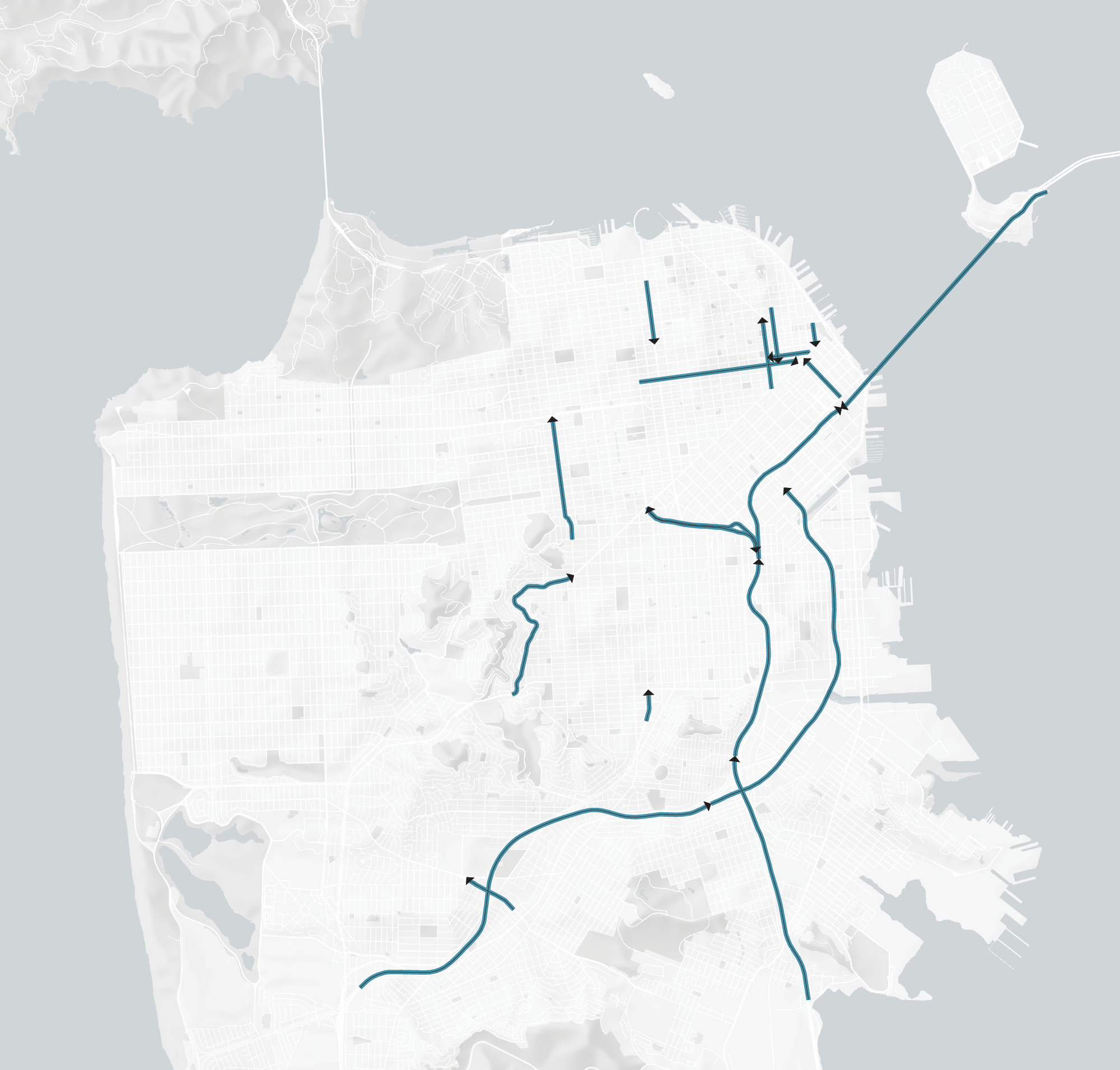

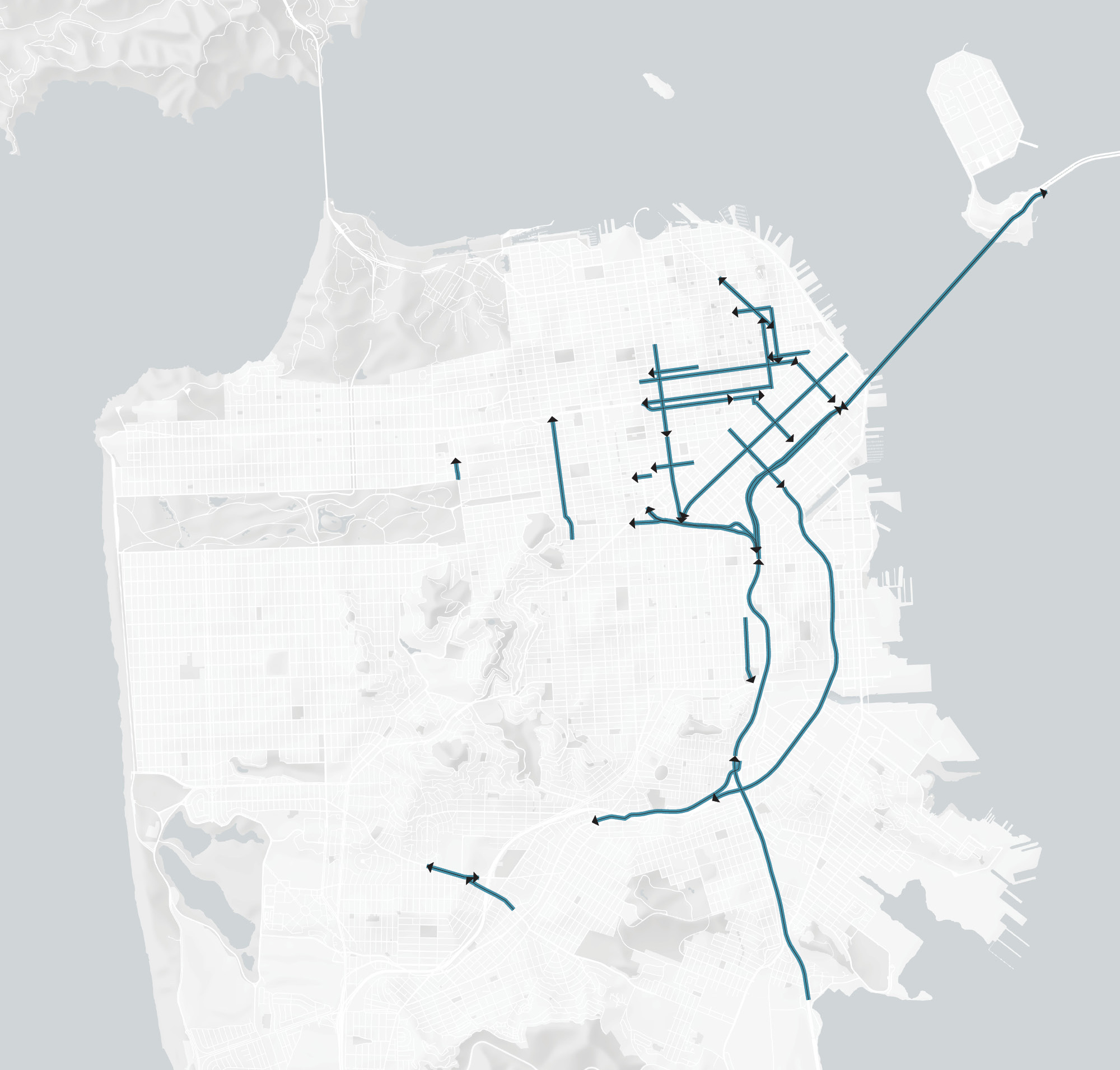

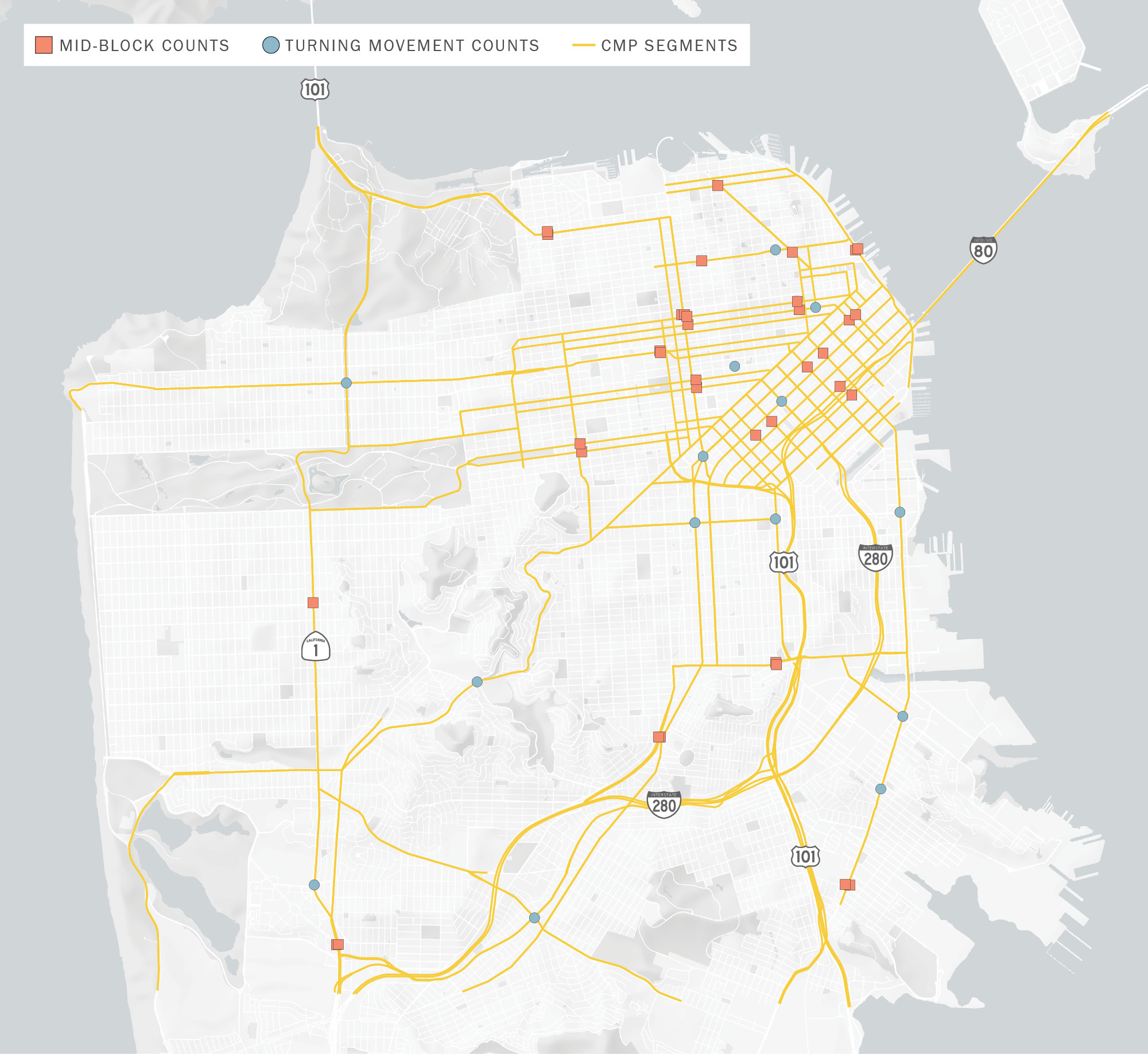

Multimodal Counts

The City and County of San Francisco has placed a high priority on supporting walking and cycling/rolling modes (including bicycling, bike share and shuttles) to facilitate active and affordable means of travel. Multimodal counts have been collected at 29 mid-block locations (vehicle only) (Figure 0-10 and Figure 0-11) and 14 intersections (vehicle, bicycle (Figure 0-12), and pedestrian (Figure 0-13) since 2015.

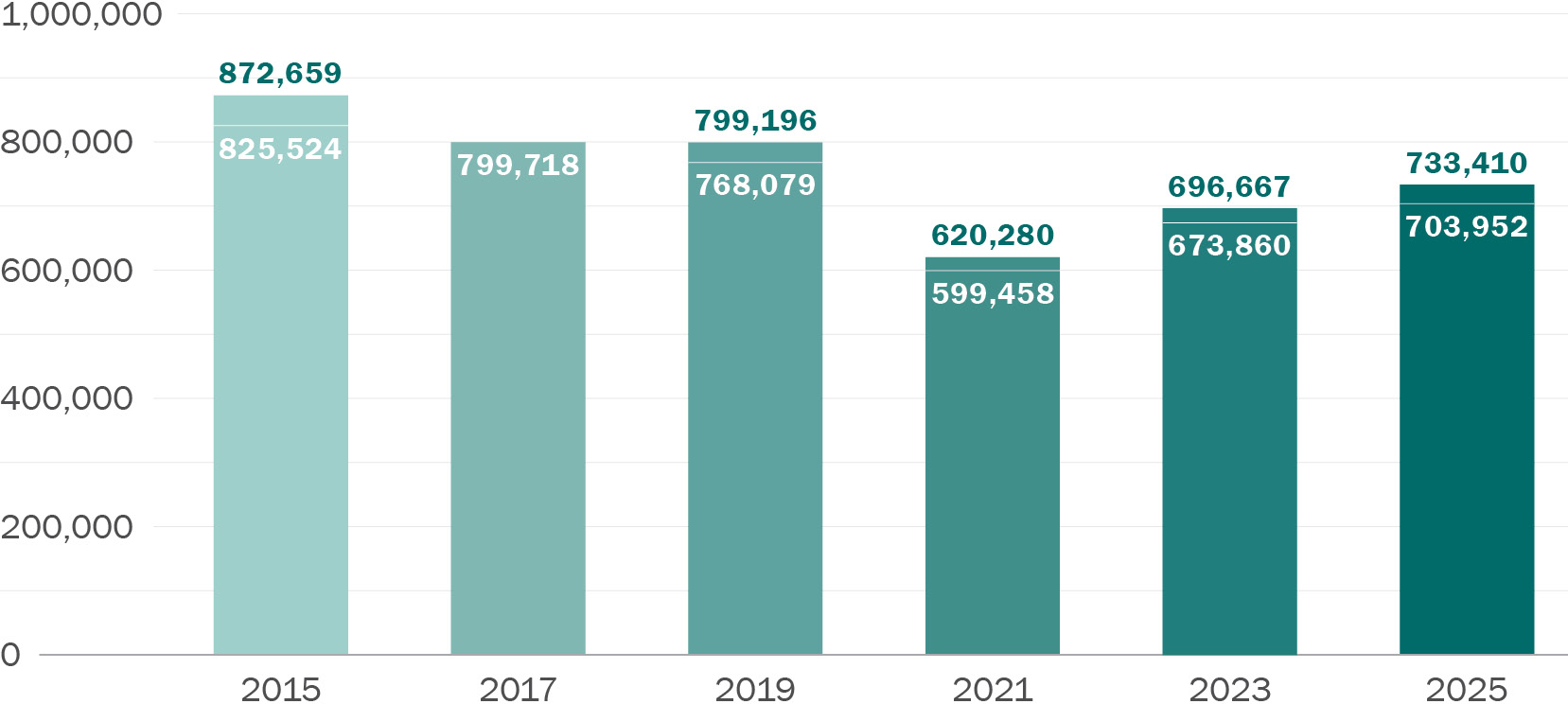

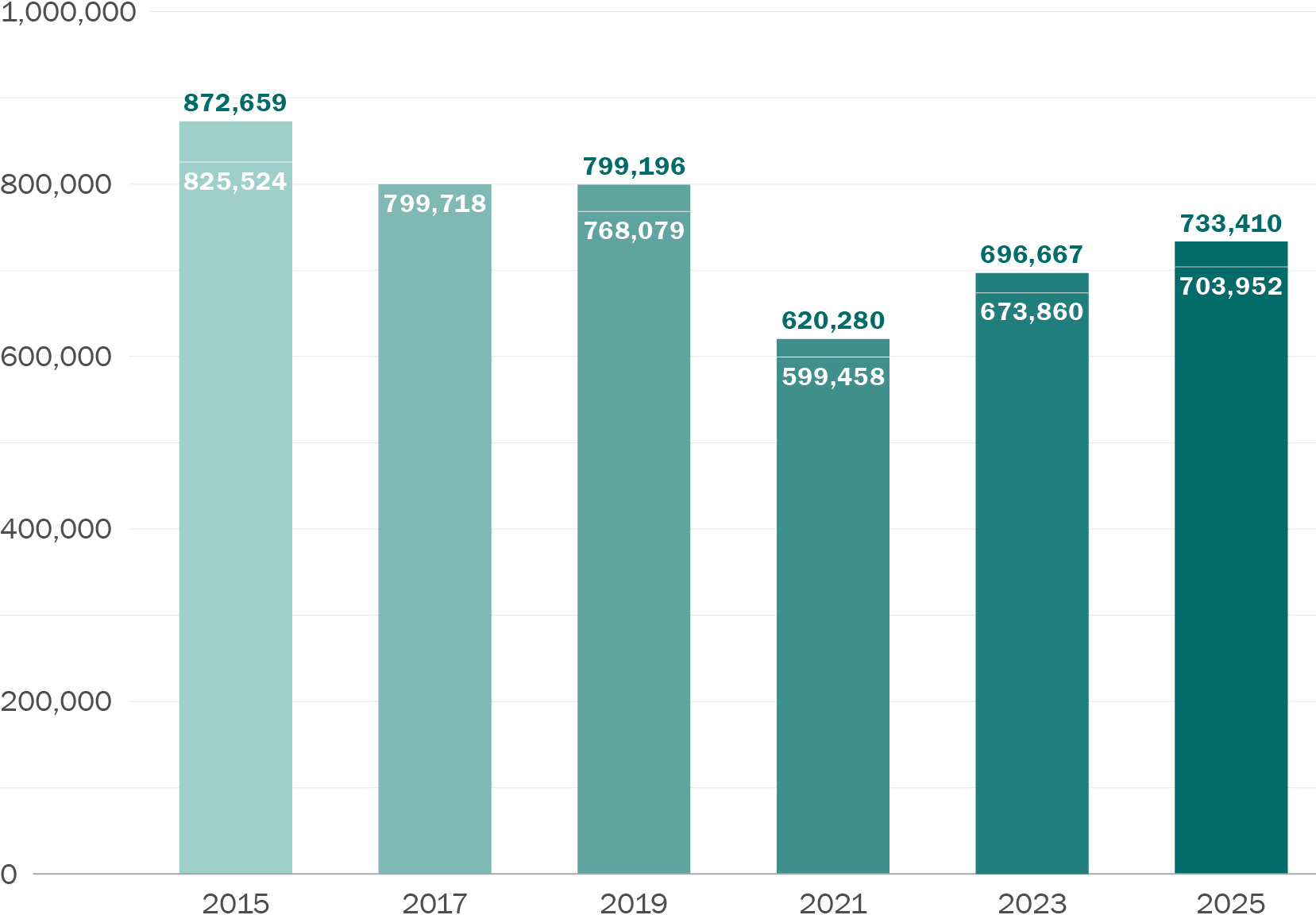

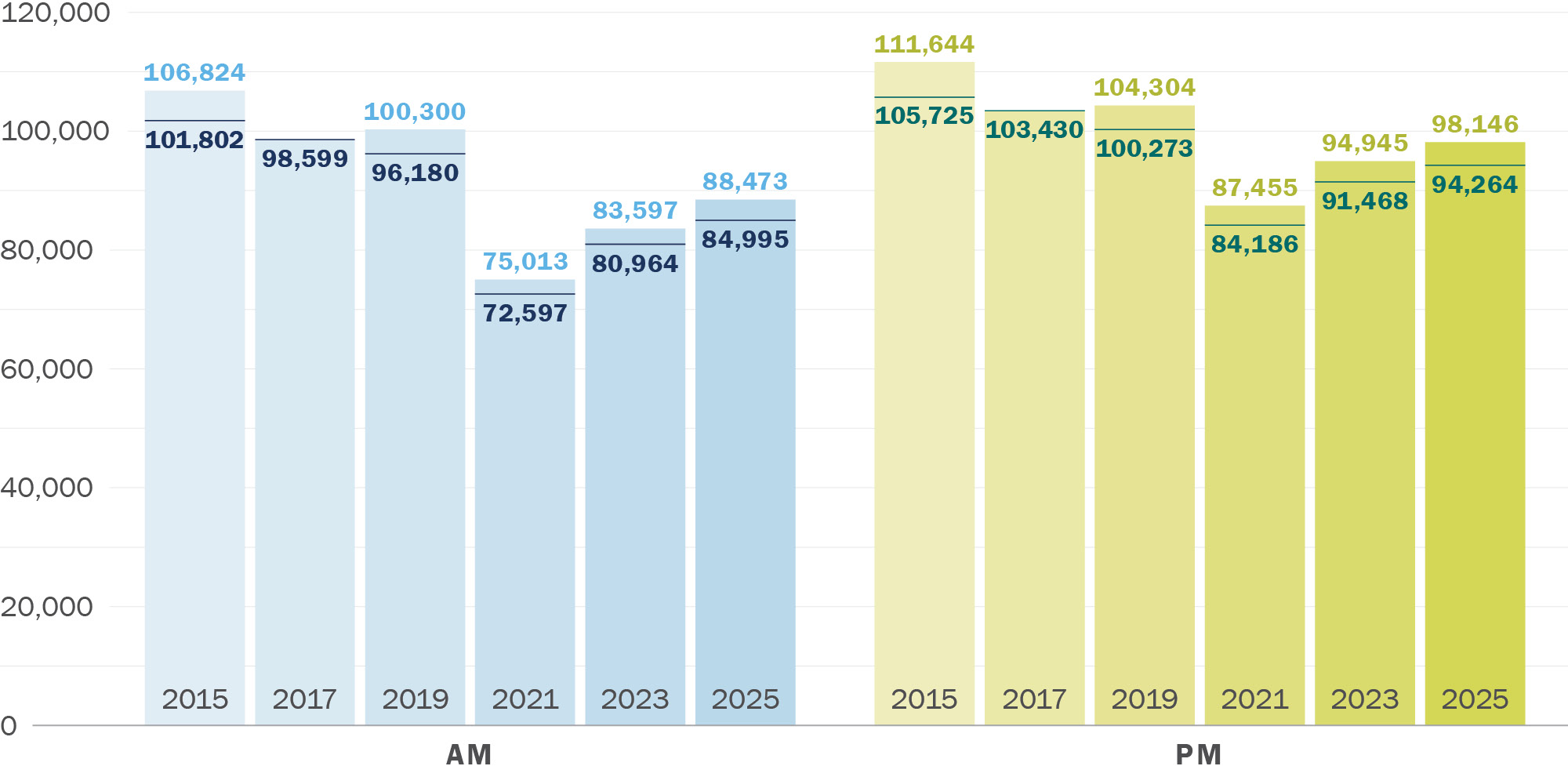

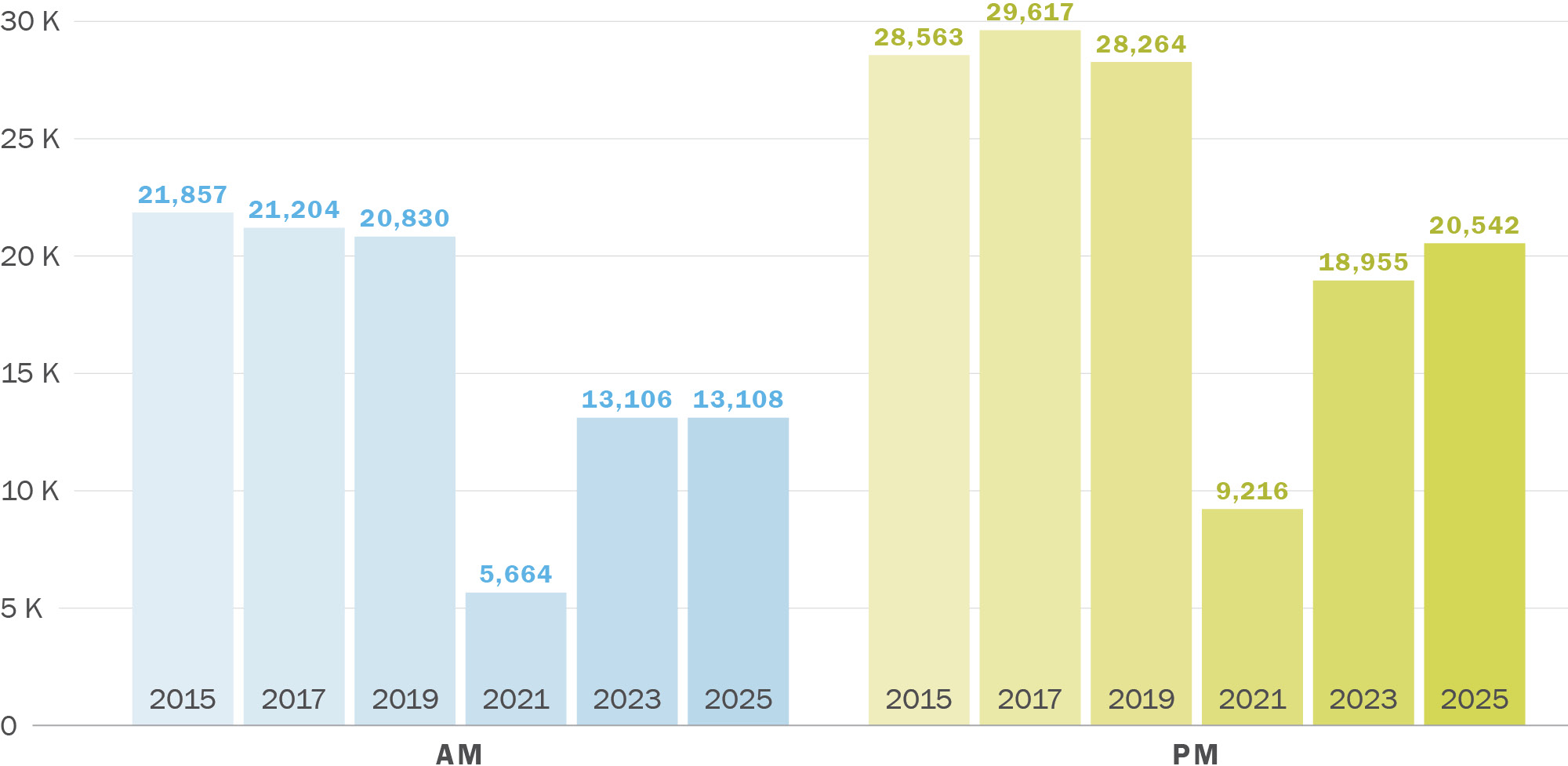

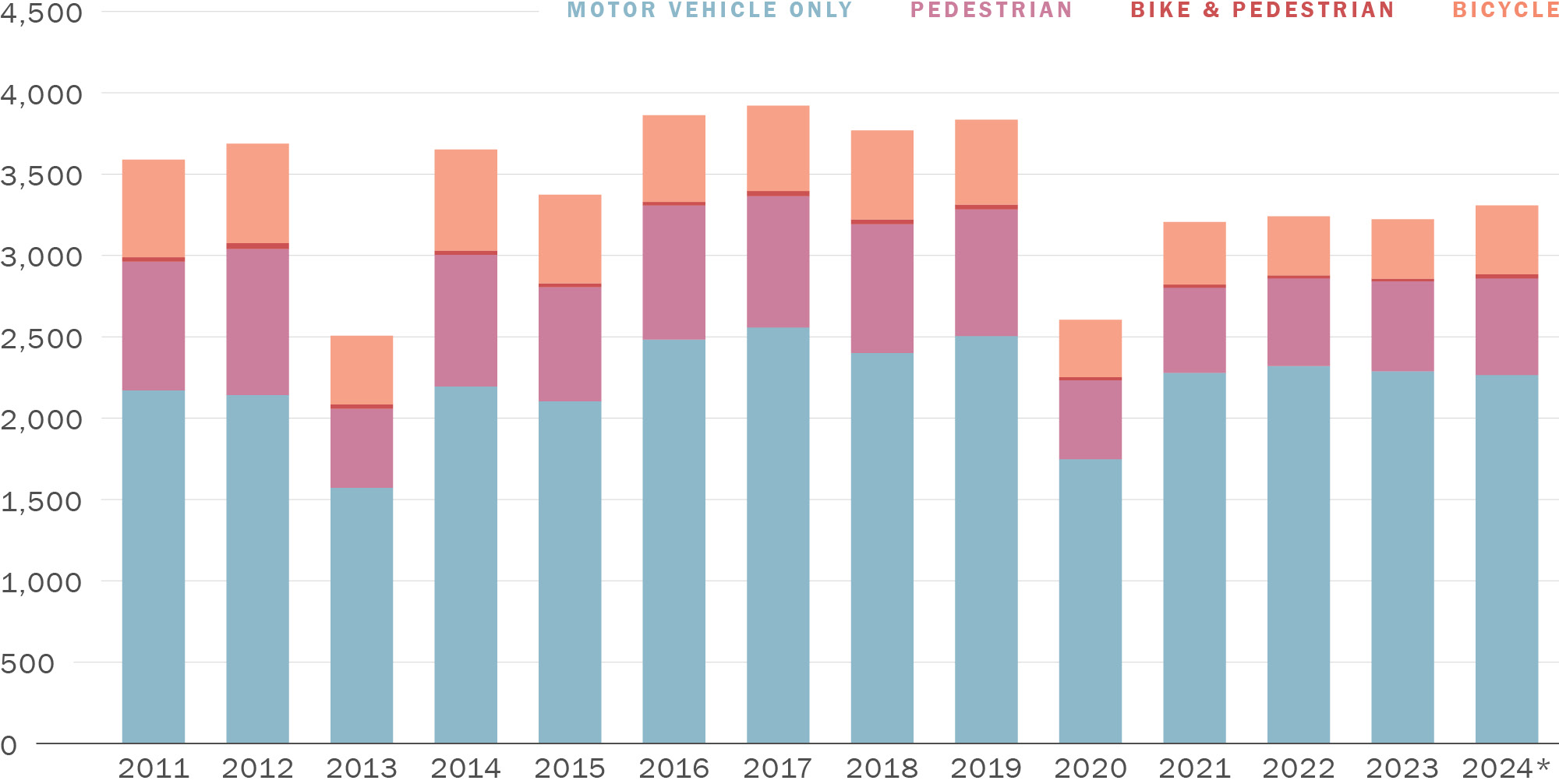

Vehicle Volumes

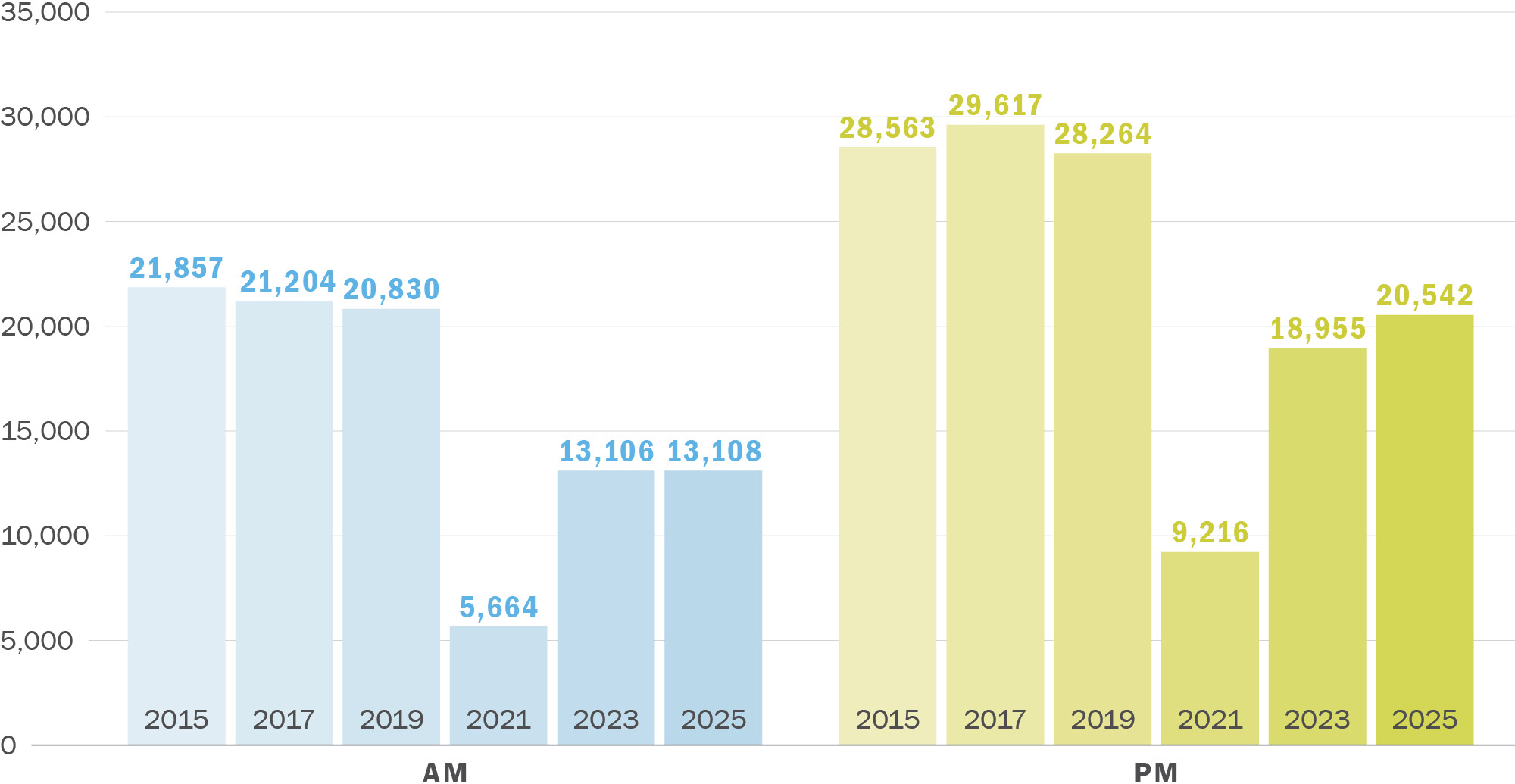

Mid-block mid-week average daily traffic continued to increase between 2023 and 2025 (+4%), reaching 92% of pre-COVID pandemic (2019) levels (Figure 0-10). The 2025 AM Peak and PM Peak mid-block mid-week vehicle counts stand at 88% and 92% of 2019 (pre-COVID pandemic) levels, respectively. The trendlines may also suggest that the ongoing vehicular traffic decrease observed from 2015 to 2019 is continuing past the COVID pandemic.A data error in 2023 midblock traffic counts was discovered that resulted in lower AM Peak period counts. This error is corrected in the 2025 CMP.

Note: Data collected April – May biennially at the same locations, counts shown for the bars are summed over all 29 locations and directions, whereas the white line within each bar only shows counts summed over 28 locations and directions (excluding counts from Van Ness between California and Pine, where no data were collected in 2017).

Download chart data (CSV)

Note: Data collected April – May biennially at the same locations, counts shown for the columns are summed over all 29 locations and directions, whereas the line within each column only shows counts summed over 28 locations and directions (excluding counts from Van Ness between California and Pine, where no data were collected in 2017).

Download chart data (CSV)

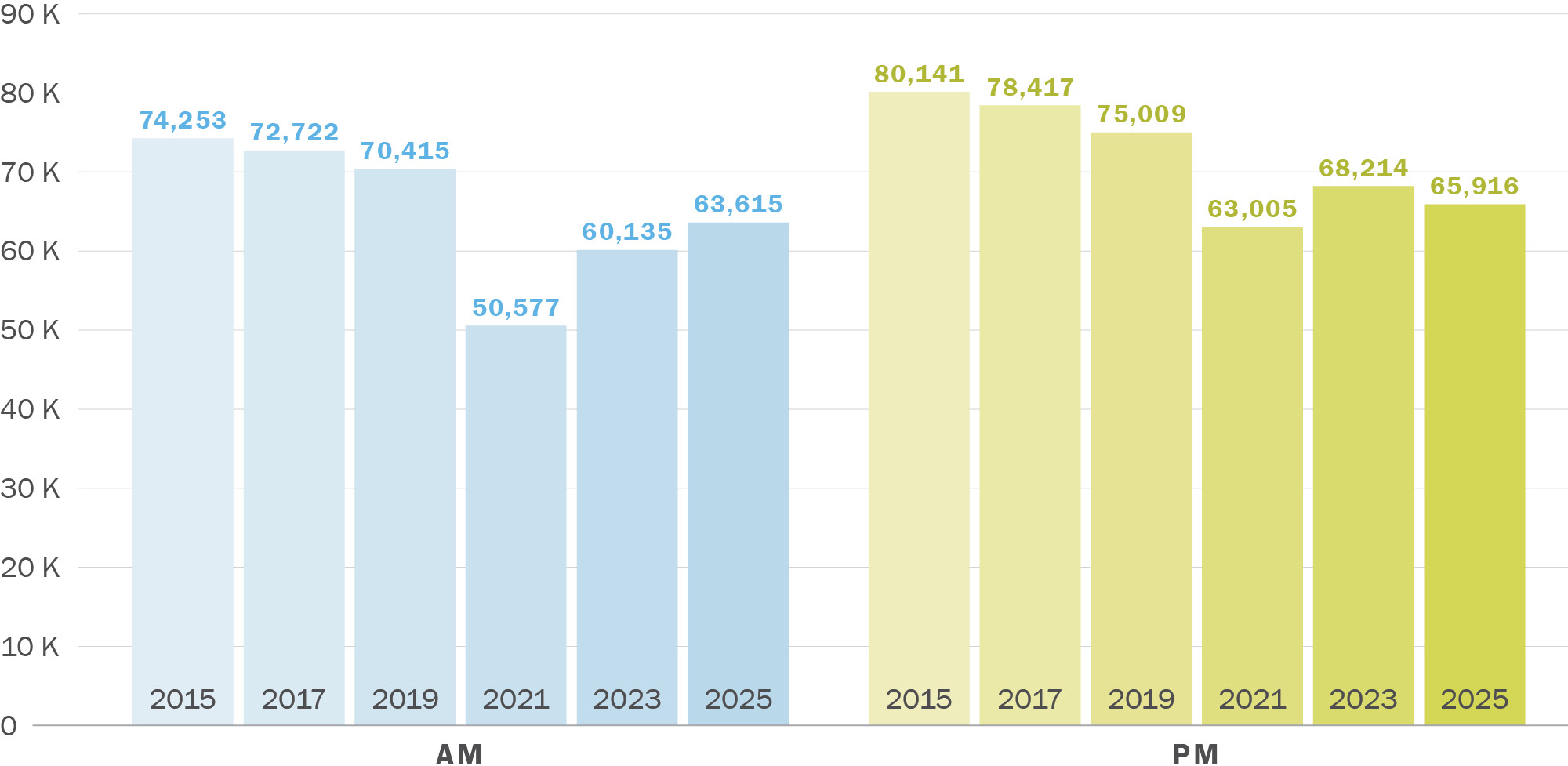

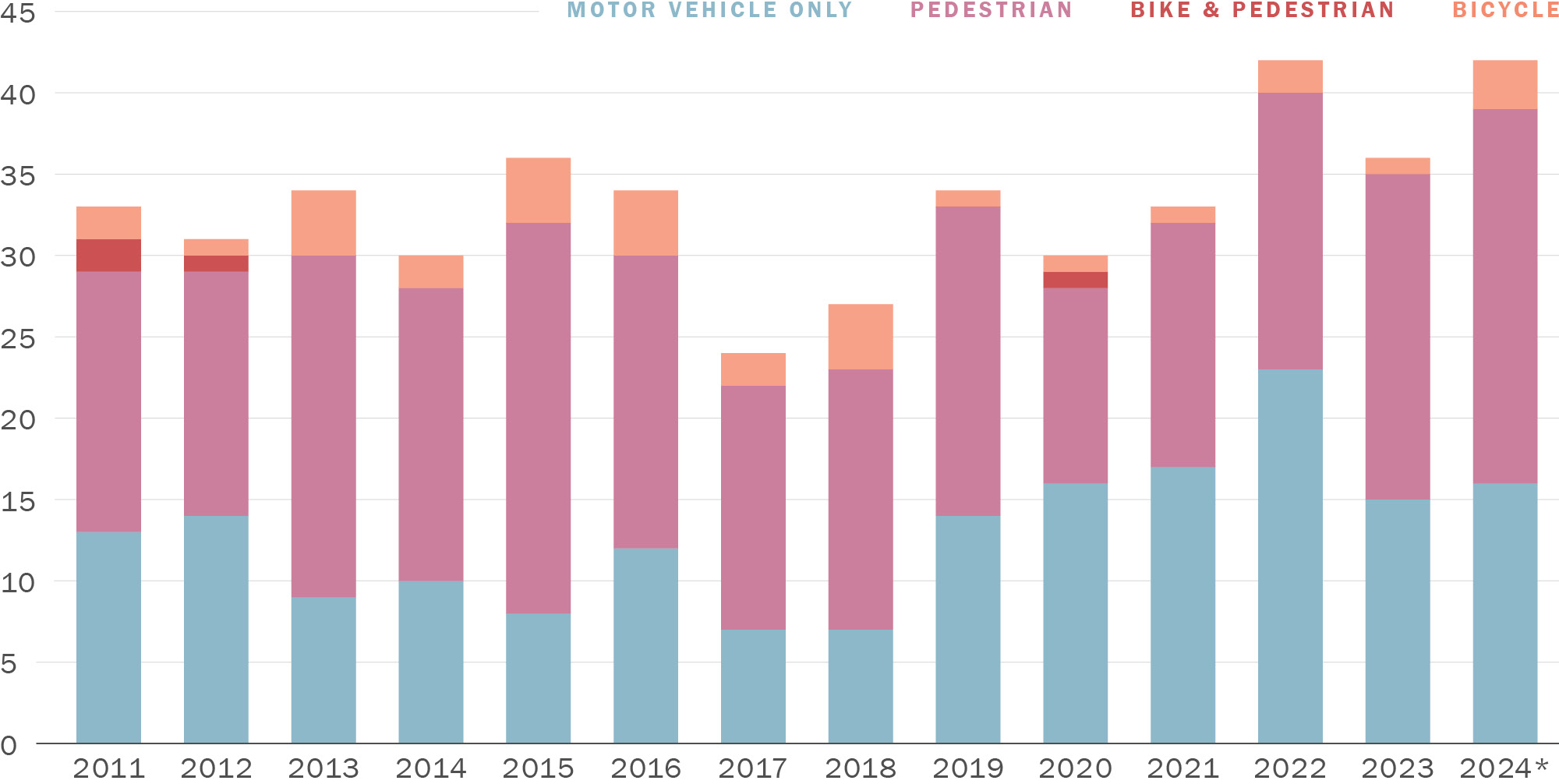

Bicycle and Pedestrian Volumes

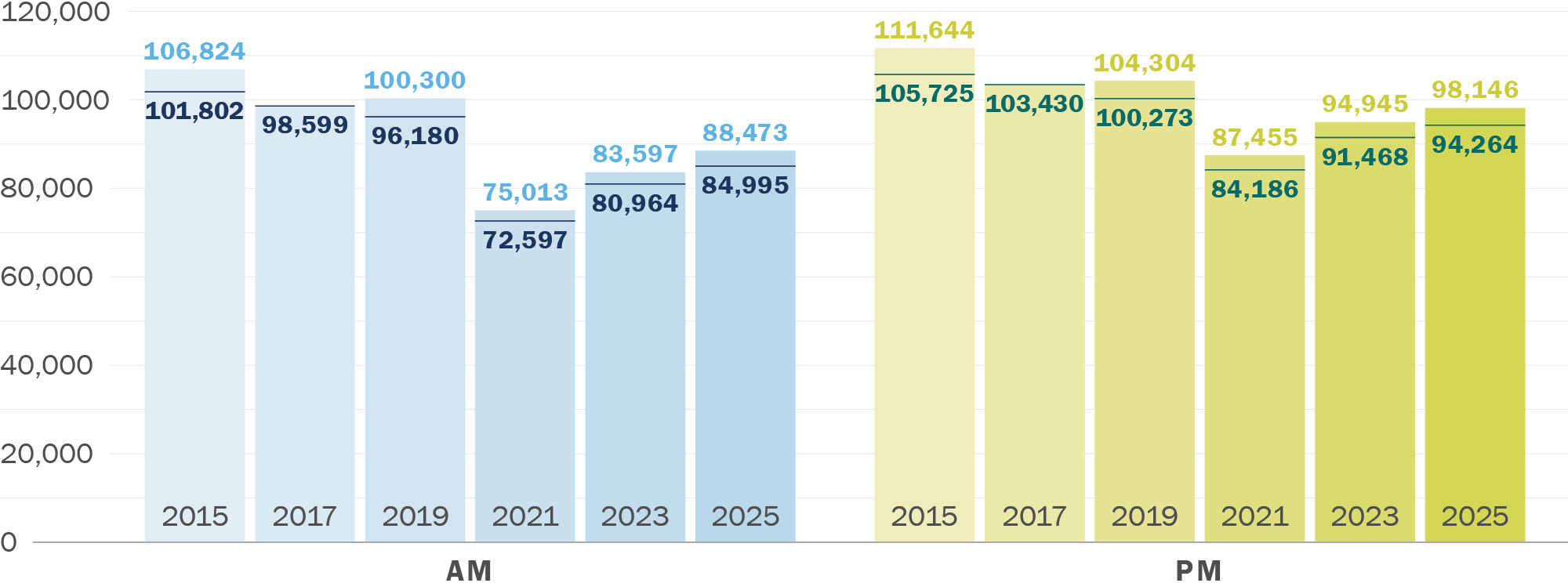

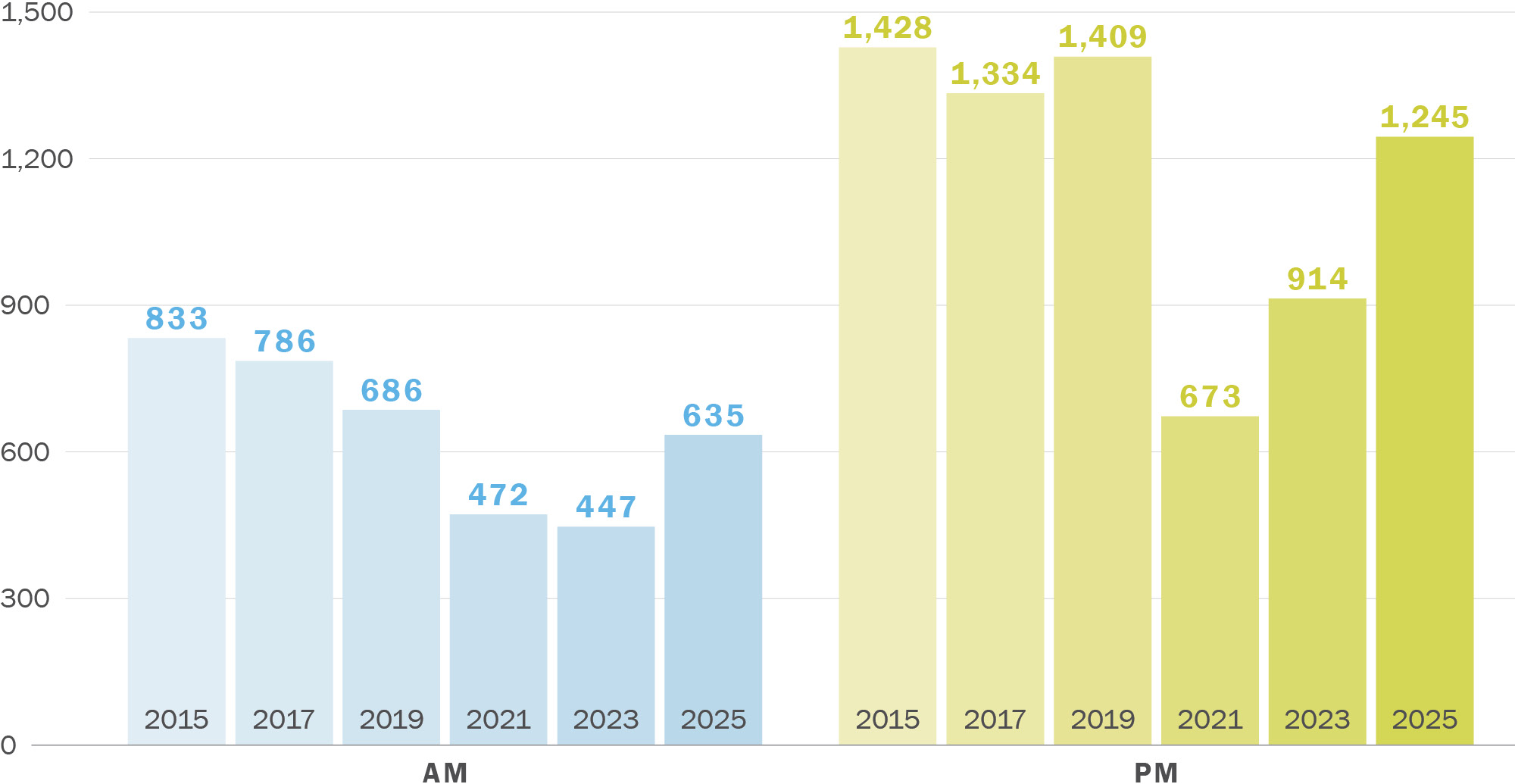

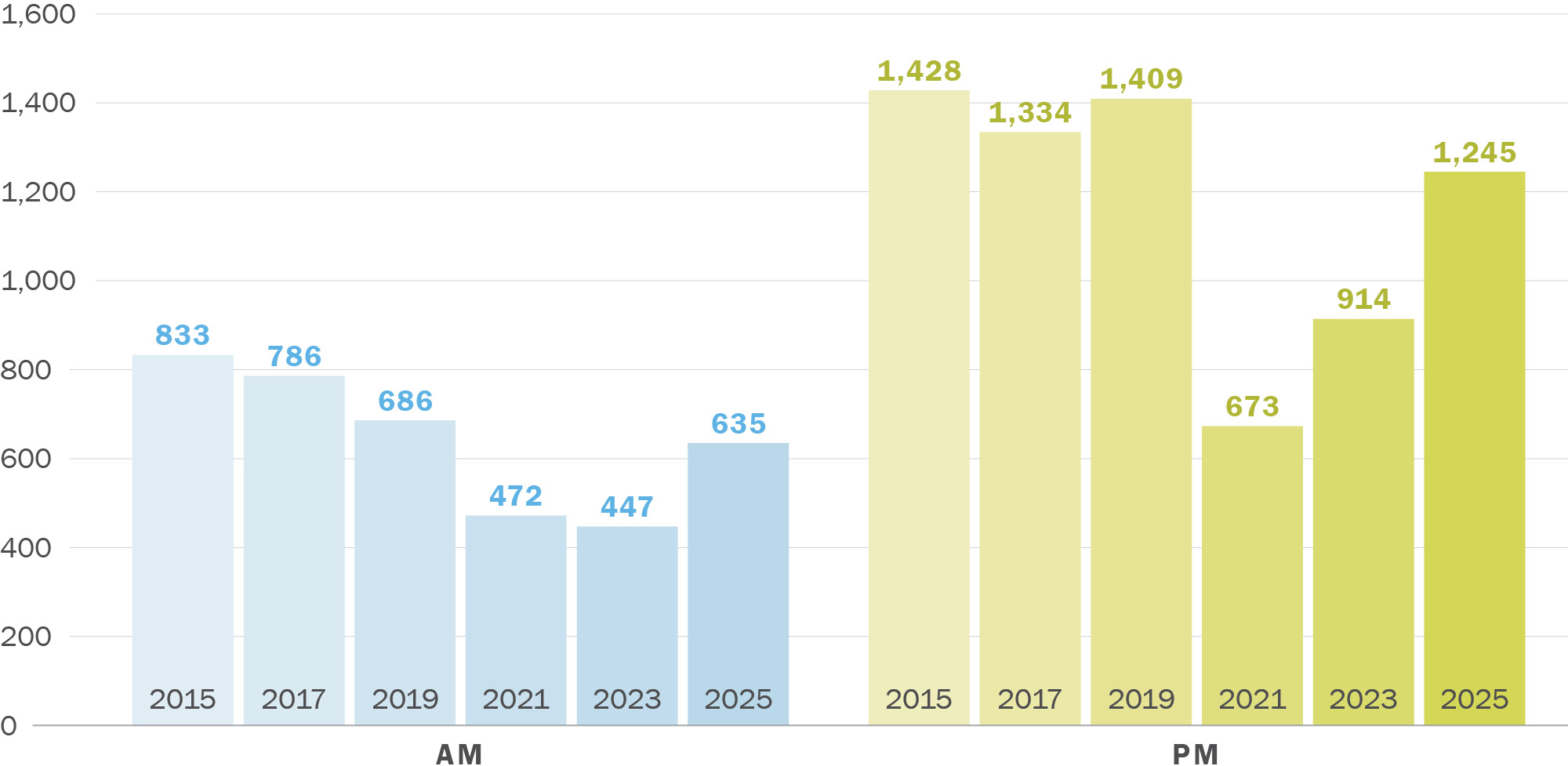

Figure 0-12 and Figure 0-13 respectively show bicycle and pedestrian counts collected by SFCTA between 2015 and 2025 throughout the city. In contrast to vehicle counts, bicycle and pedestrian intersection counts show a stronger recovery in the PM Peak than the AM Peak. Bicycle counts showed a particularly strong increase between 2023 and 2025 of +42% for the AM Peak and +36% for the PM Peak. Pedestrian counts saw more modest changes between 2023 and 2025, with AM Peak counts basically unchanged (+0%), and PM Peak counts increasing +8%.

AM Peak vs PM Peak Travel

Taken together, travel in the PM Peak (4:30 – 6:30 p.m.) seems to show a slight mode shift from automobiles to bicycles and walking. This shift away from automobiles is not observed in the AM Peak (7:00 – 0 a.m.) however.

Note: Data collected April – May biennially at the same locations, counts shown are summed over all locations.

Download chart data (CSV)

Note: Data collected April – May biennially at the same locations, counts shown are summed over all locations.

Download chart data (CSV)

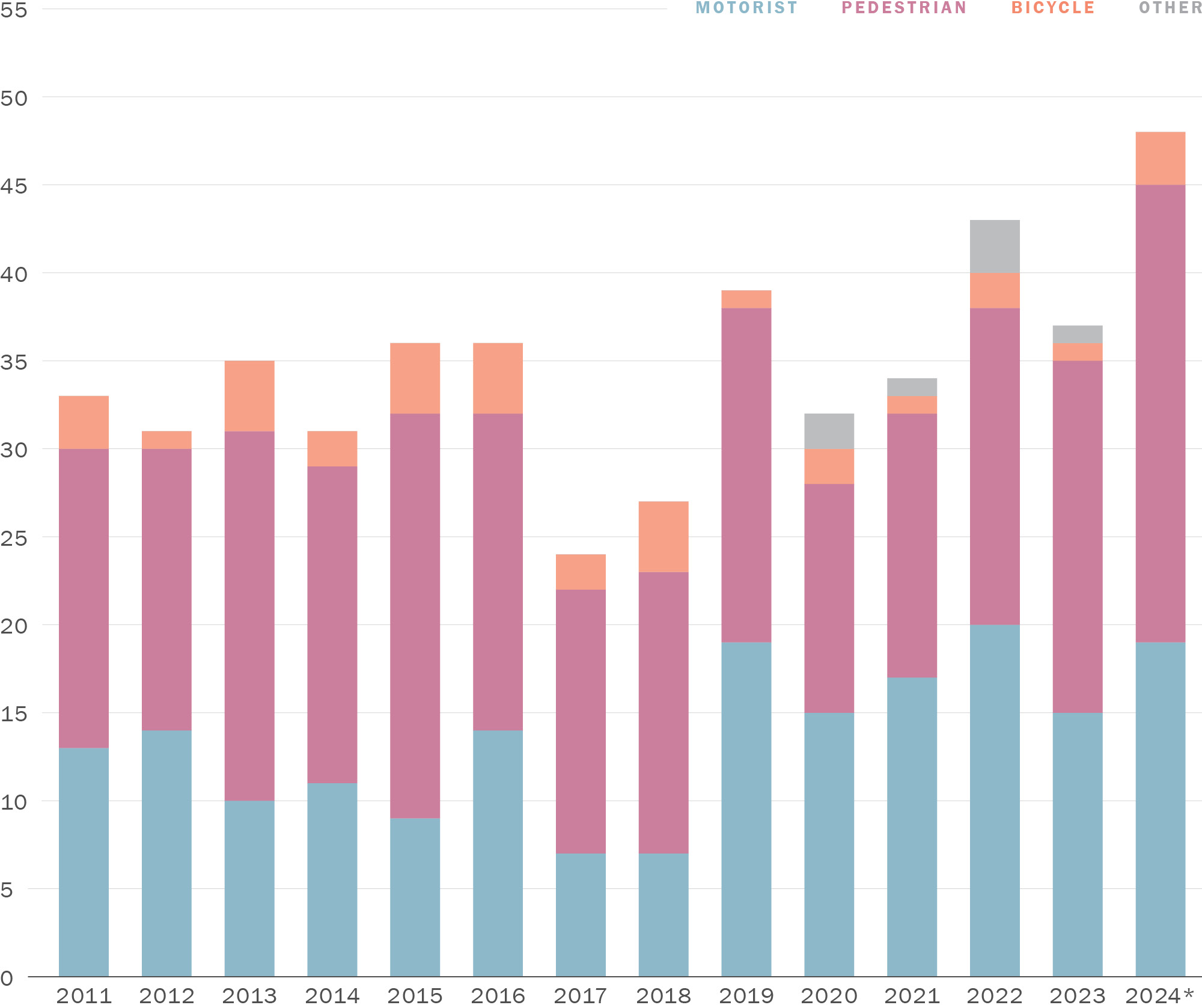

Traffic Safety

Safety for road users, including those walking or biking, are key measures of transportation performance, and a critical policy priority for San Francisco. The City and County of San Francisco adopted Vision Zero as a policy in 2014, committing to build better and safer streets, educate the public on traffic safety, enforce traffic laws, and adopt policy changes that save lives. The San Francisco Street Safety Act (July 2025) re-affirmed San Francisco’s commitment to traffic safety and identified specific activities across city agencies to advance the city’s goals.

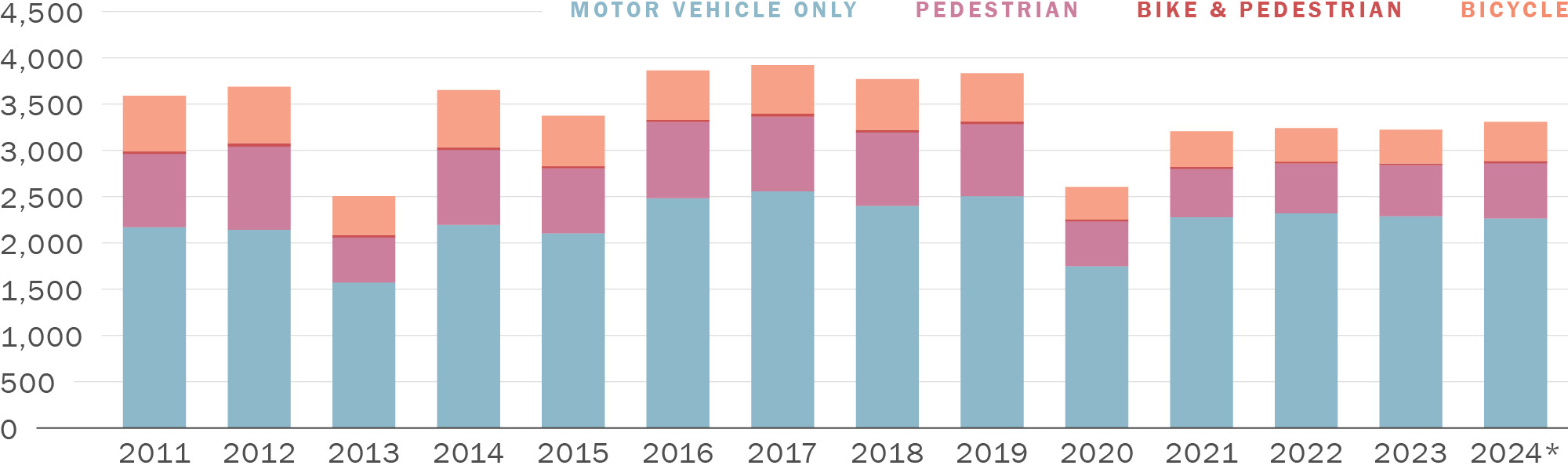

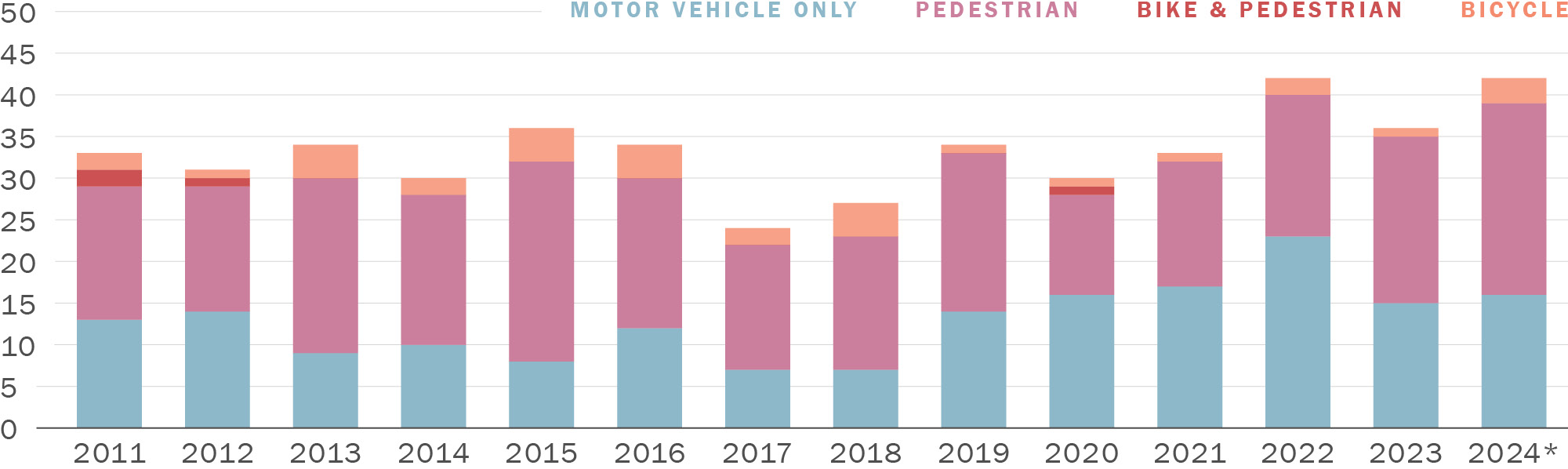

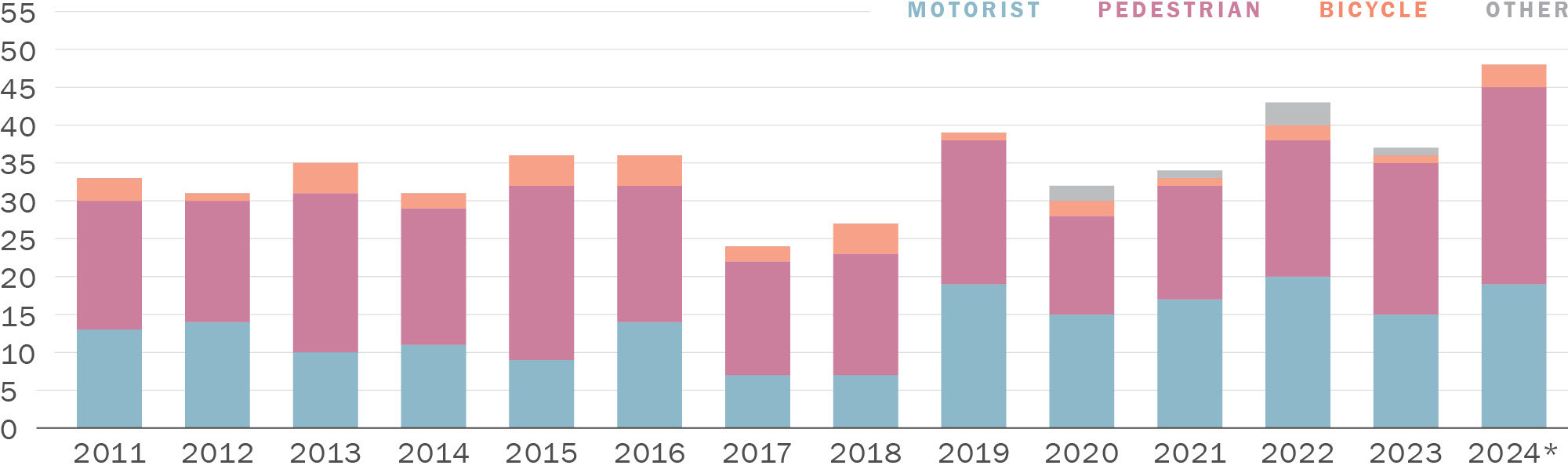

The number of injury collisions (involving people walking or biking) dropped significantly in 2020, probably due to the substantial reduction in vehicle and non-motorized volumes in 2020 due to the COVID pandemic. Speeding remains a top collision factor and concern during this time, among the “Focus on the 5” priorities for SFMTA counter-measure and San Francisco Police Department traffic enforcement efforts. The number of property-damage only (PDO) collisions, non-severe injury collisions, and severe injury collisions have increased from 2020 lows, but remain mostly stable below pre-pandemic highs as of 2024 (Figure 0-14). The total number of fatal collisions in 2024 at 42 (of which 23 and 3 involved people walking and biking, respectively), however, is the highest observed since 2011 (other than 2022 which has the same number of fatal collisions) (Figure 0-15). Total fatalities also increased to their highest level observed since 2011, reaching 48 (Figure 0-16). These totals are higher than those reported through San Francisco’s Vision Zero program, which exclude fatalities that occur on freeways.

* provisional data.

Download chart data (CSV)

* provisional data.

Download chart data (CSV)

* provisional data.

Download chart data (CSV)

Mode Share

Mode share describes the mix of modes, such as transit, biking, walking, and driving used to travel to, from, and within San Francisco. Figure 0-17, Figure 0-18, and Figure 0-19 summarize the share of trips by mode for trips in San Francisco broken down into three different travel markets: all trips to/from/within San Francisco, regional trips to/from San Francisco (trips where one of the trip ends is in San Francisco and the other is not), and trips within San Francisco (trips that both start and end in San Francisco). Driving (alone, sharing a ride, or using a TNC) is the most prevalent mode to both get around within San Francisco (43.9%) and to travel to/from San Francisco (76.3%). For travel within San Francisco, walking is the next most prevalent mode (41.0%). There is also a significant transit share for both travel markets (11.8% for trips within San Francisco, and 21.9% for trips to/from San Francisco).

Download chart data (CSV)

Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT)

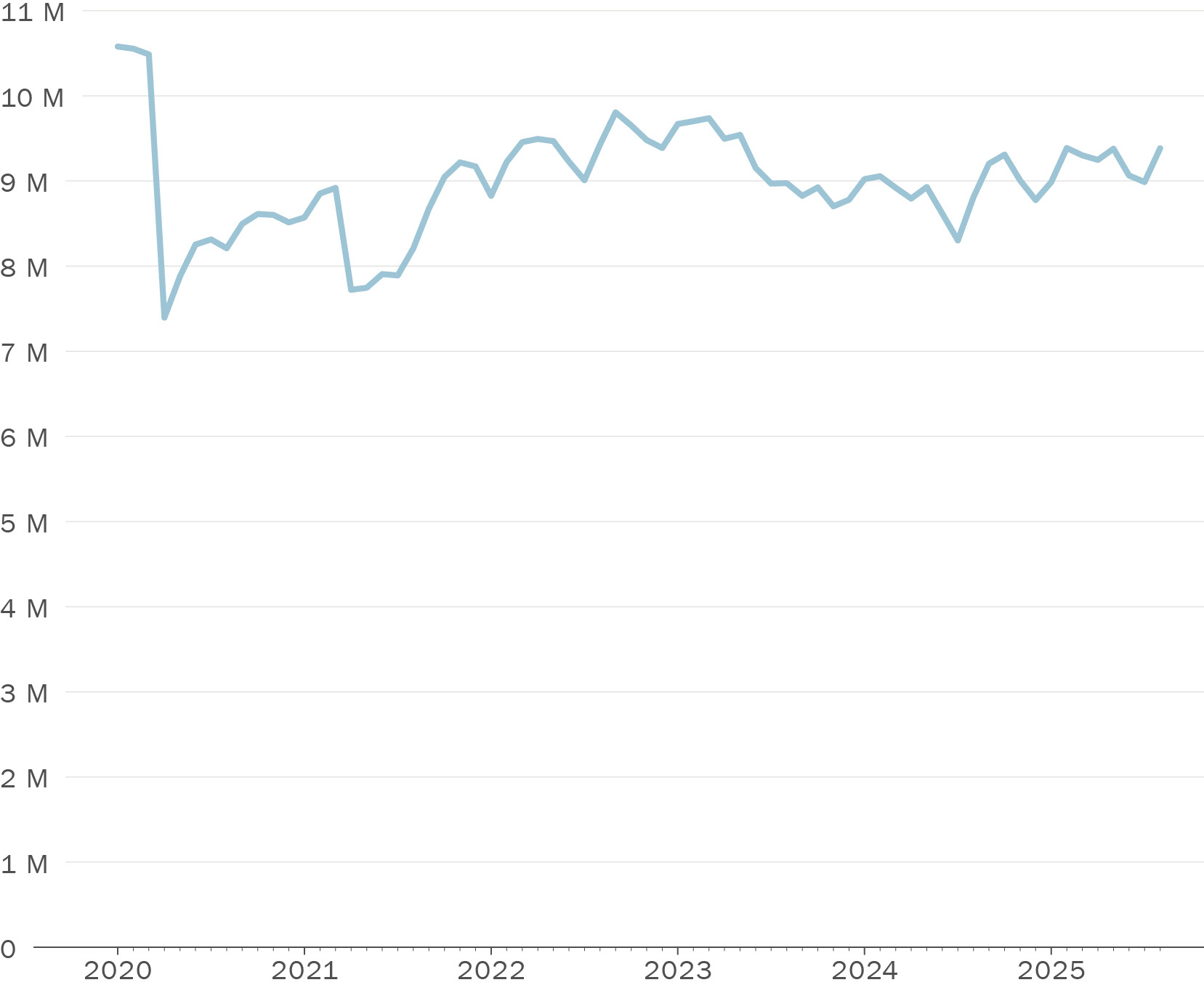

In 2016, the San Francisco Planning Commission adopted new guidelines for evaluating the transportation impacts of new projects. Critically, environmental impact determinations locally and statewide are now based on vehicle miles traveled (VMT) rather than additional automobile delay as measured by level-of-service (LOS). VMT decreased by 20 – 30% in the first 1.5 years of the COVID pandemic. As of 2025, VMT is hovering at around 10% below pre-COVID levels (Figure 0-20).

Source: The Transportation Authority, based on INRIX automobile speed data

Download chart data (CSV)

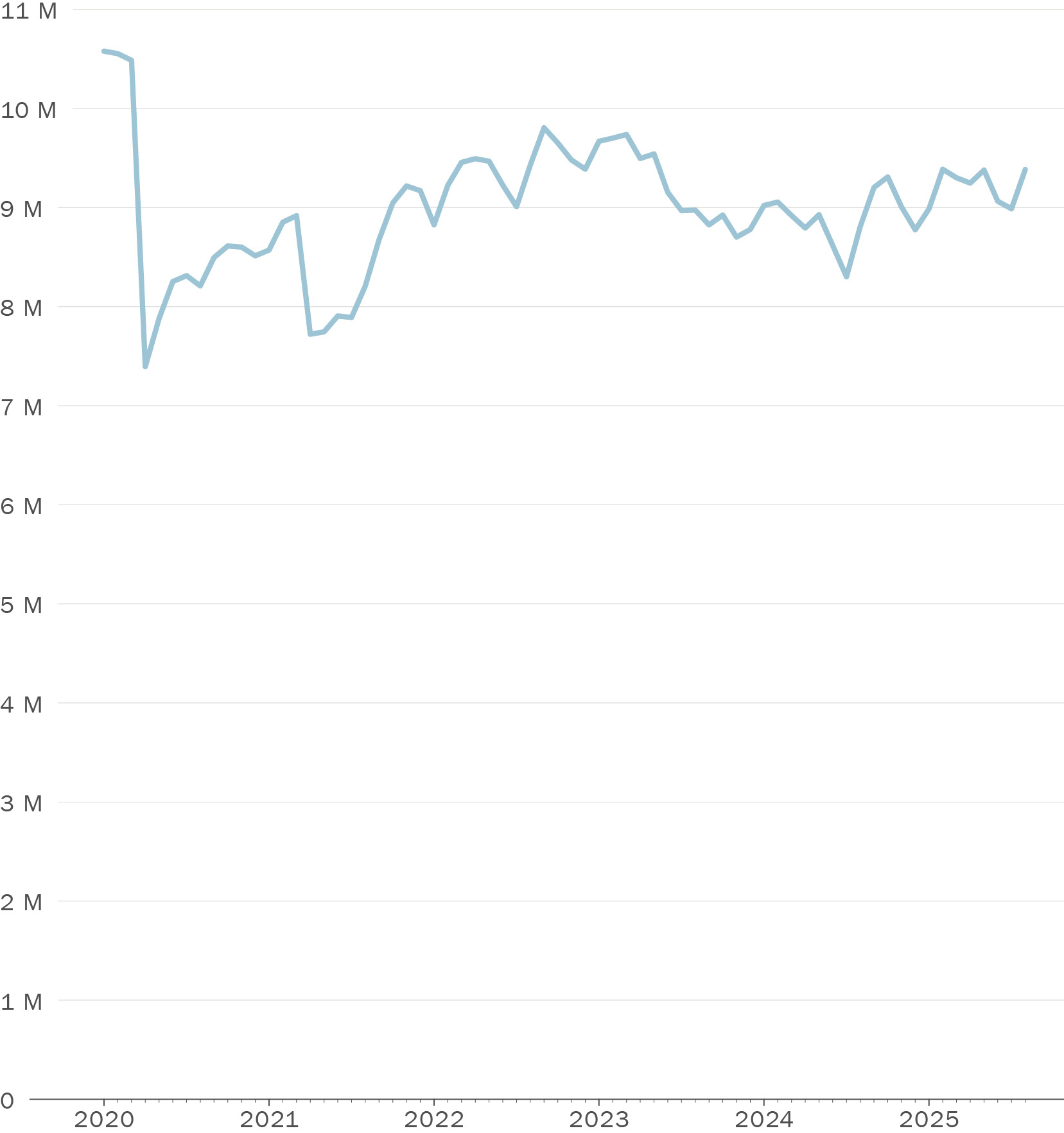

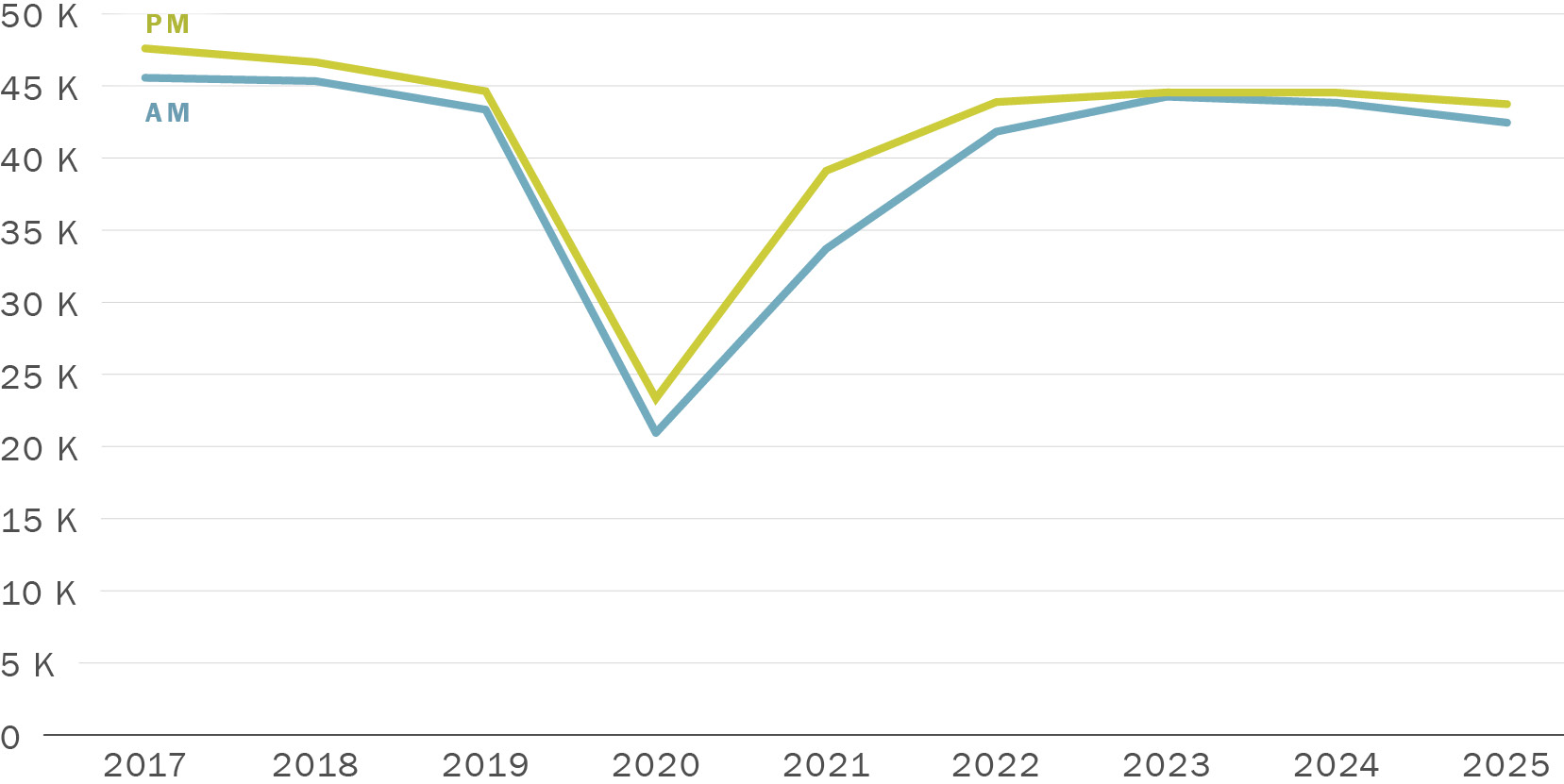

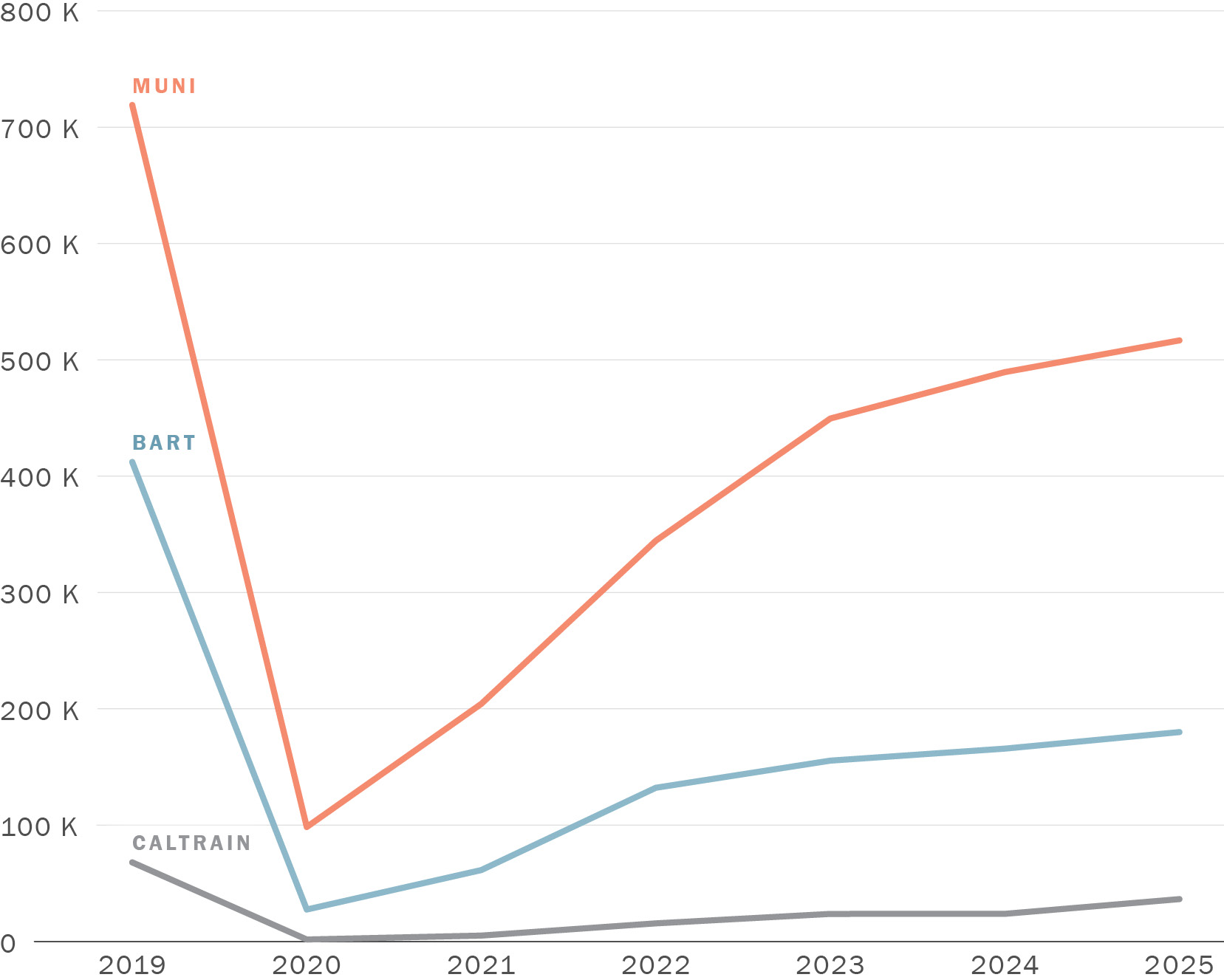

Transit Ridership

San Francisco’s strong backbone of local and regional transit has been key to our ability to manage congestion. Muni, BART, Caltrain, and commuter bus lines help move people into, out of, and around the city efficiently. Figure 0-21 shows recent ridership trends for the three largest transit systems serving San Francisco. Muni carries the greatest number of trips in San Francisco, with over 500,000 trips on a typical April – May weekday in 2025. Ridership on all three operators declined significantly with the spread of COVID in 2020. Since then, ridership has been gradually increasing every year, but in Apr – May 2025 ridership is still lower than pre-COVID pandemic levels, with Muni, BART, and Caltrain at 72%, 44%, and 54% of 2019 (pre-COVID pandemic) ridership respectively. As of October 2025 (for Muni and Caltrain) and June 2025 (for BART), ridership has further recovered to 82%, 48%, and 62% of pre-pandemic ridership for Muni, BART, and Caltrain, respectively.

Source: SFMTA/BART/Caltrain

Note: data collected April – May each year except for Caltrain it is February

Download chart data (CSV)

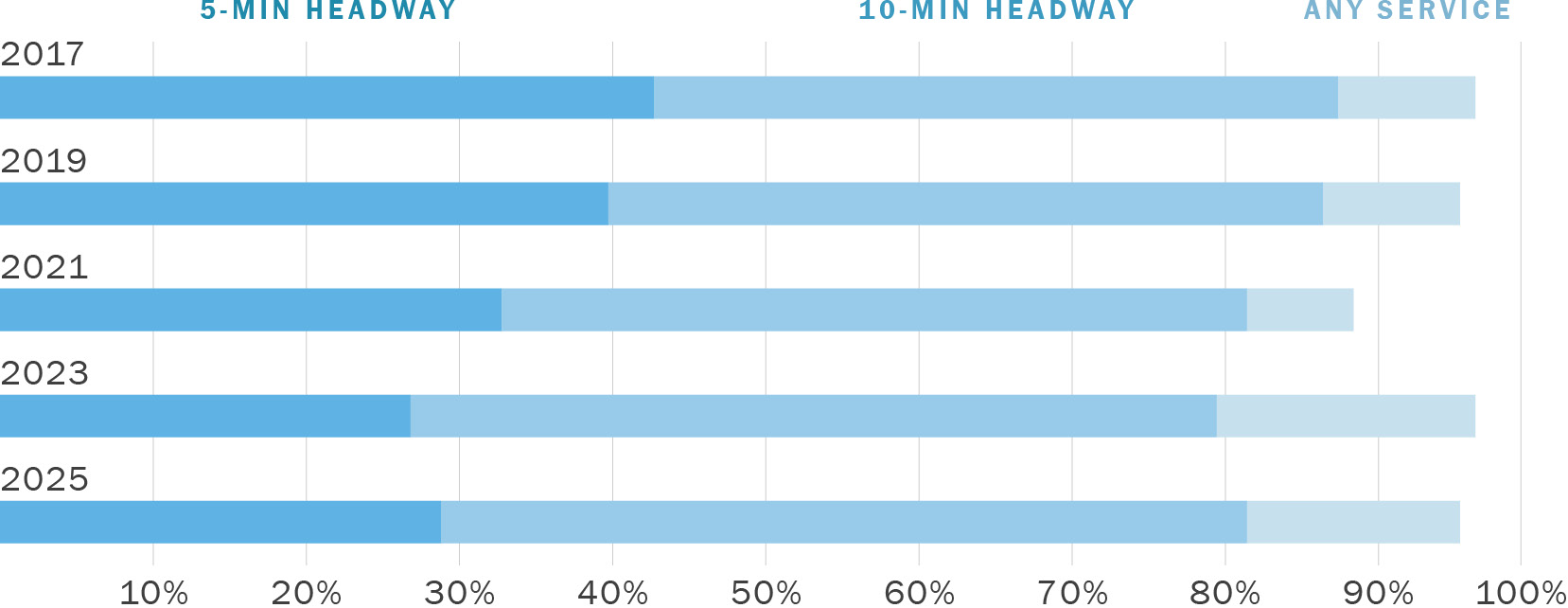

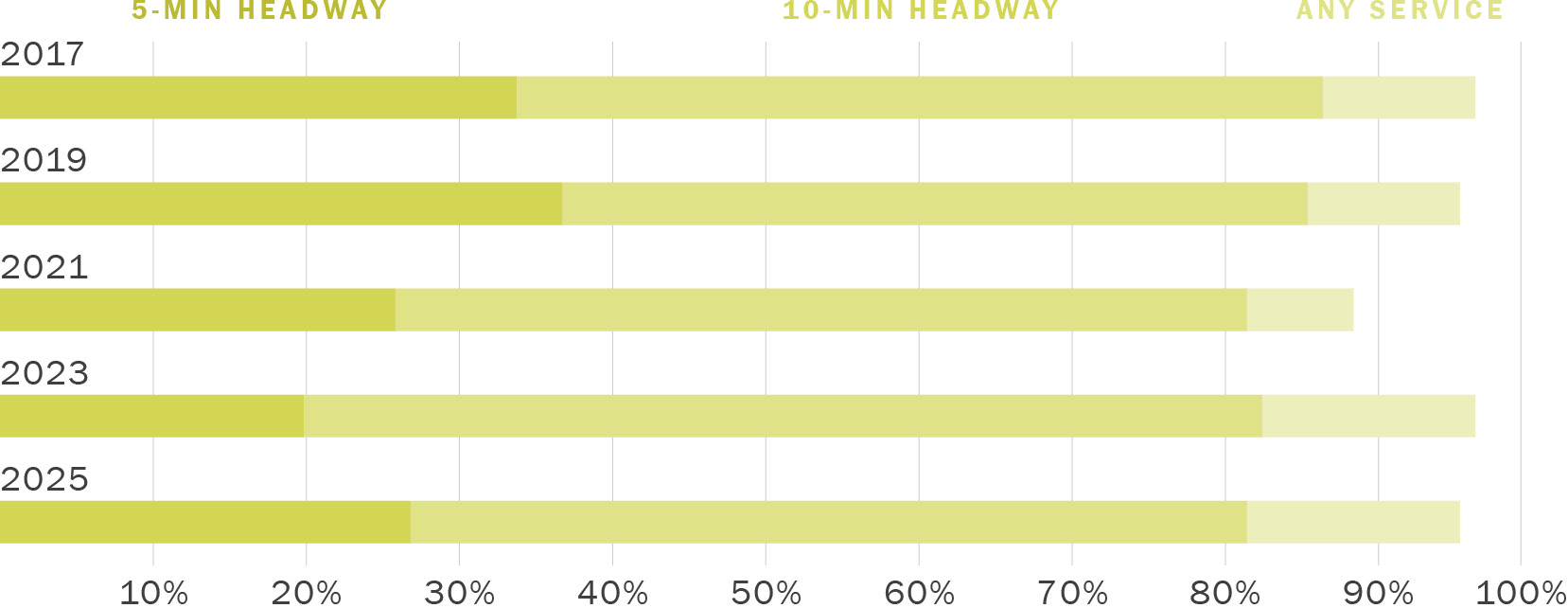

Transit Coverage

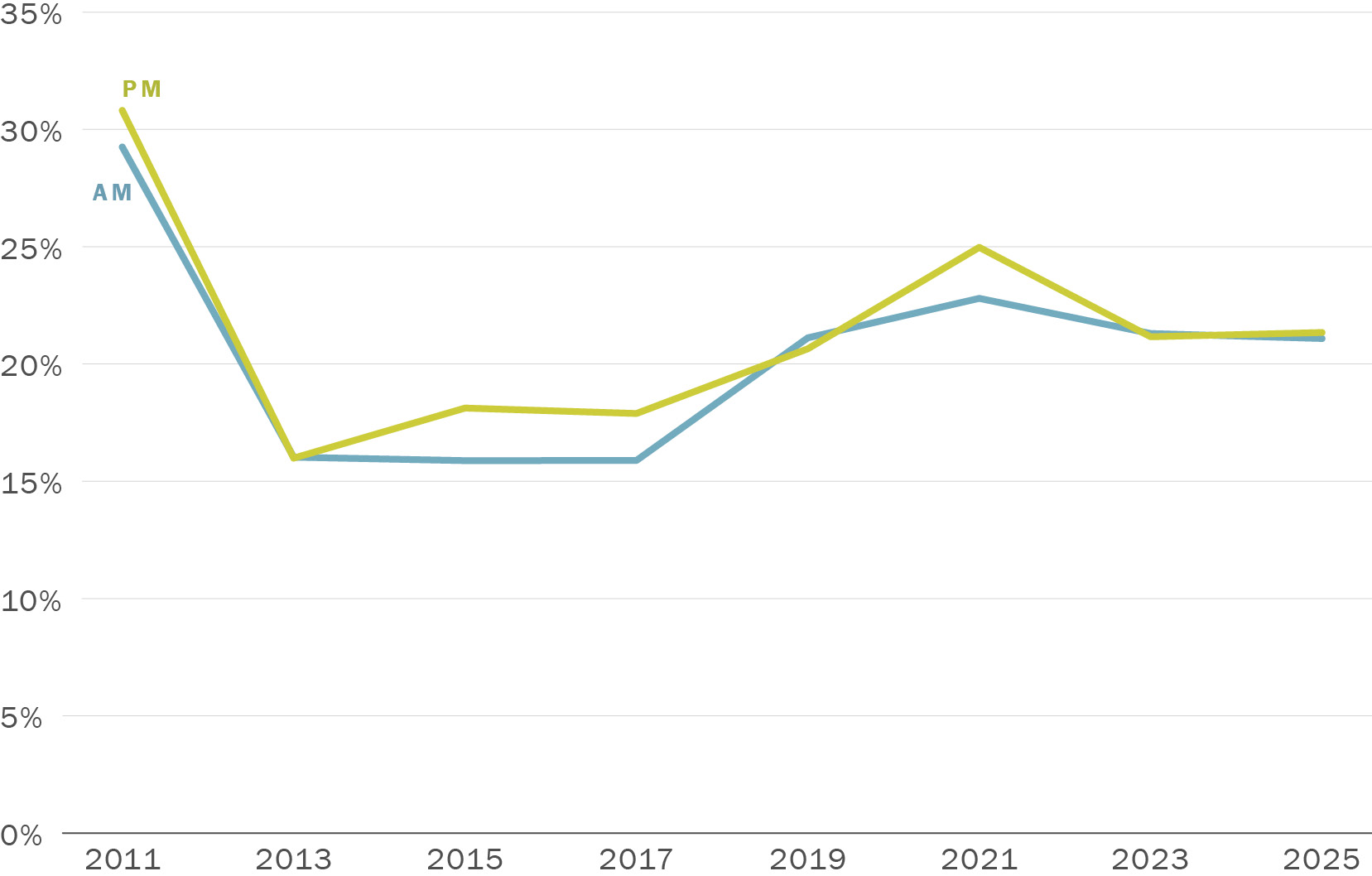

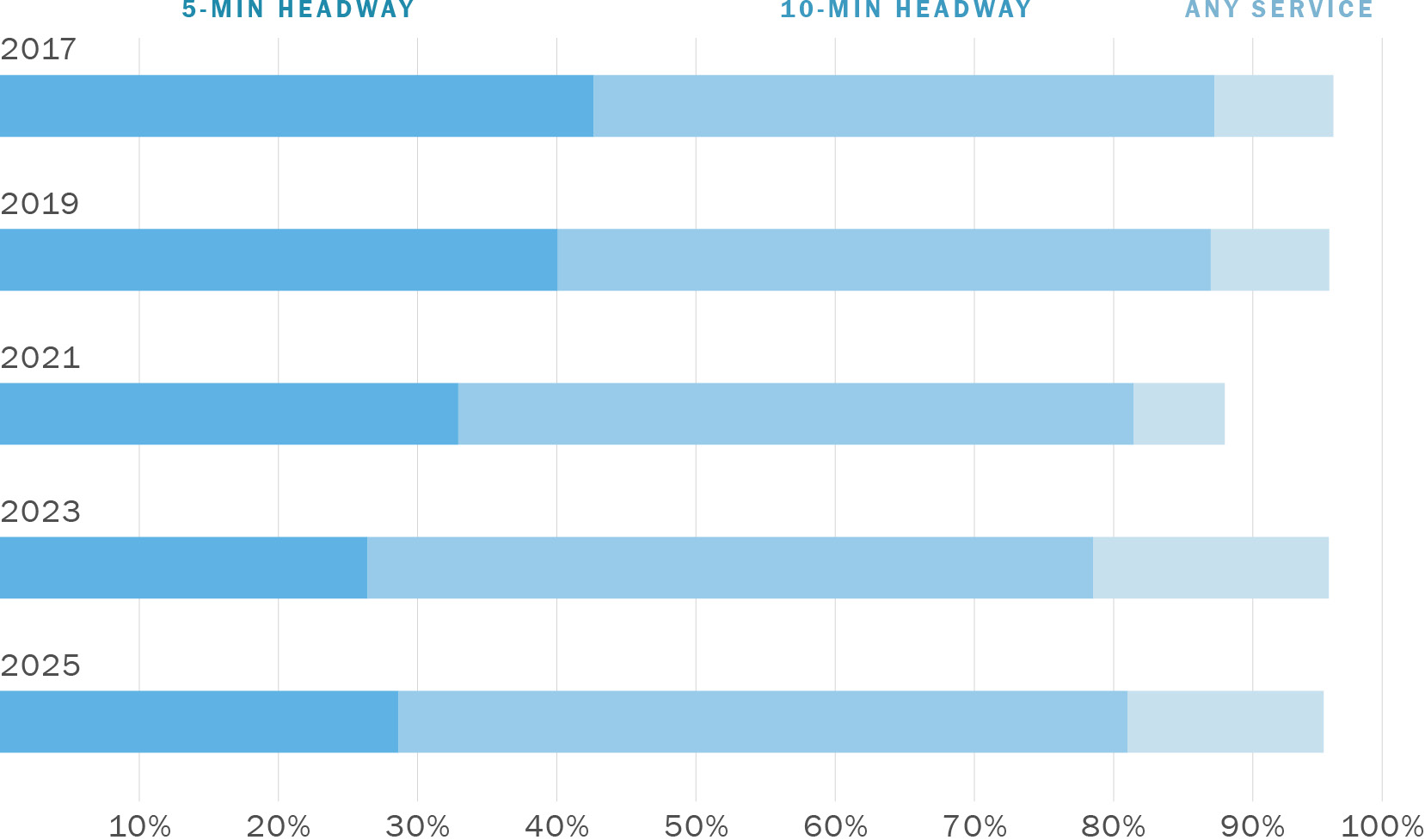

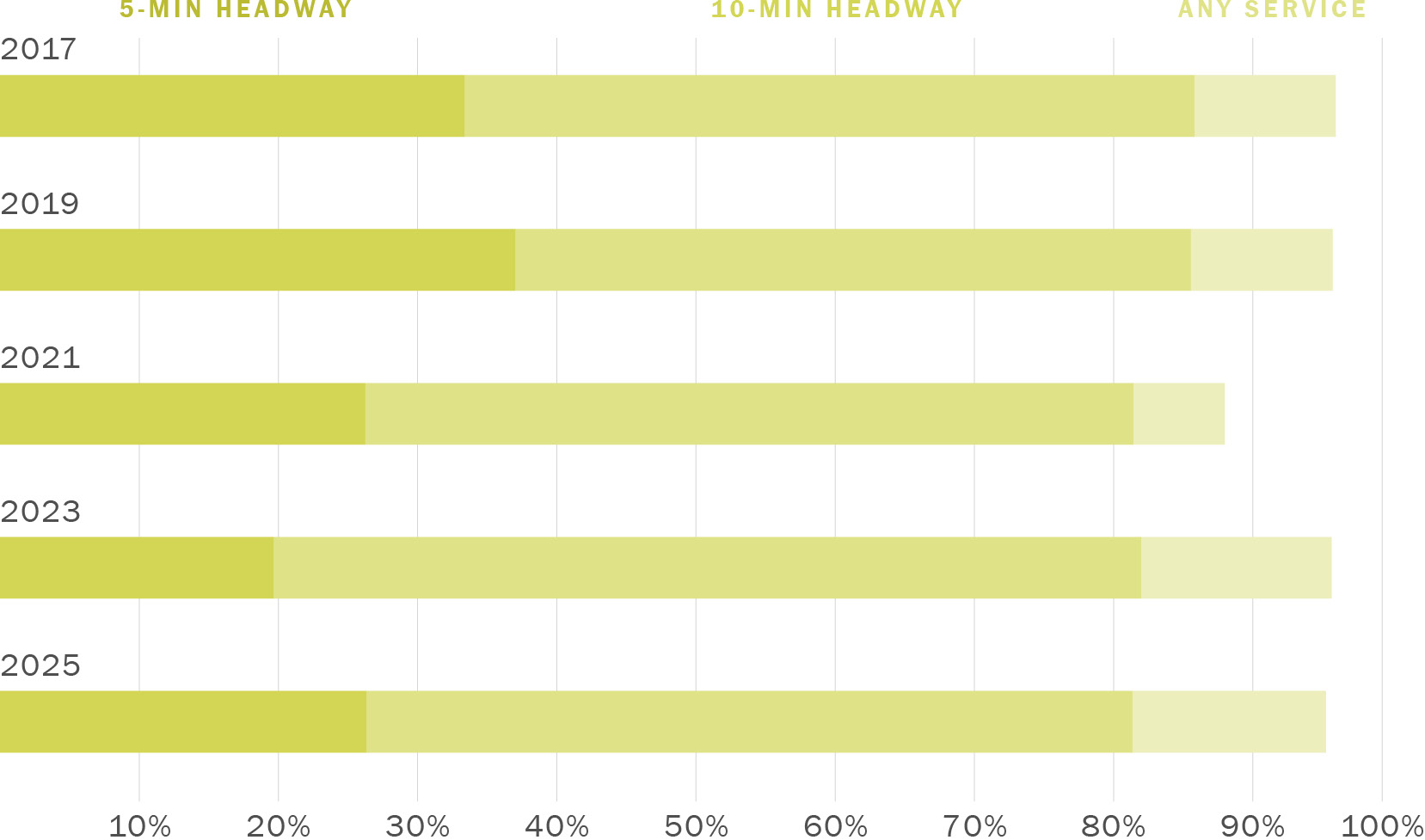

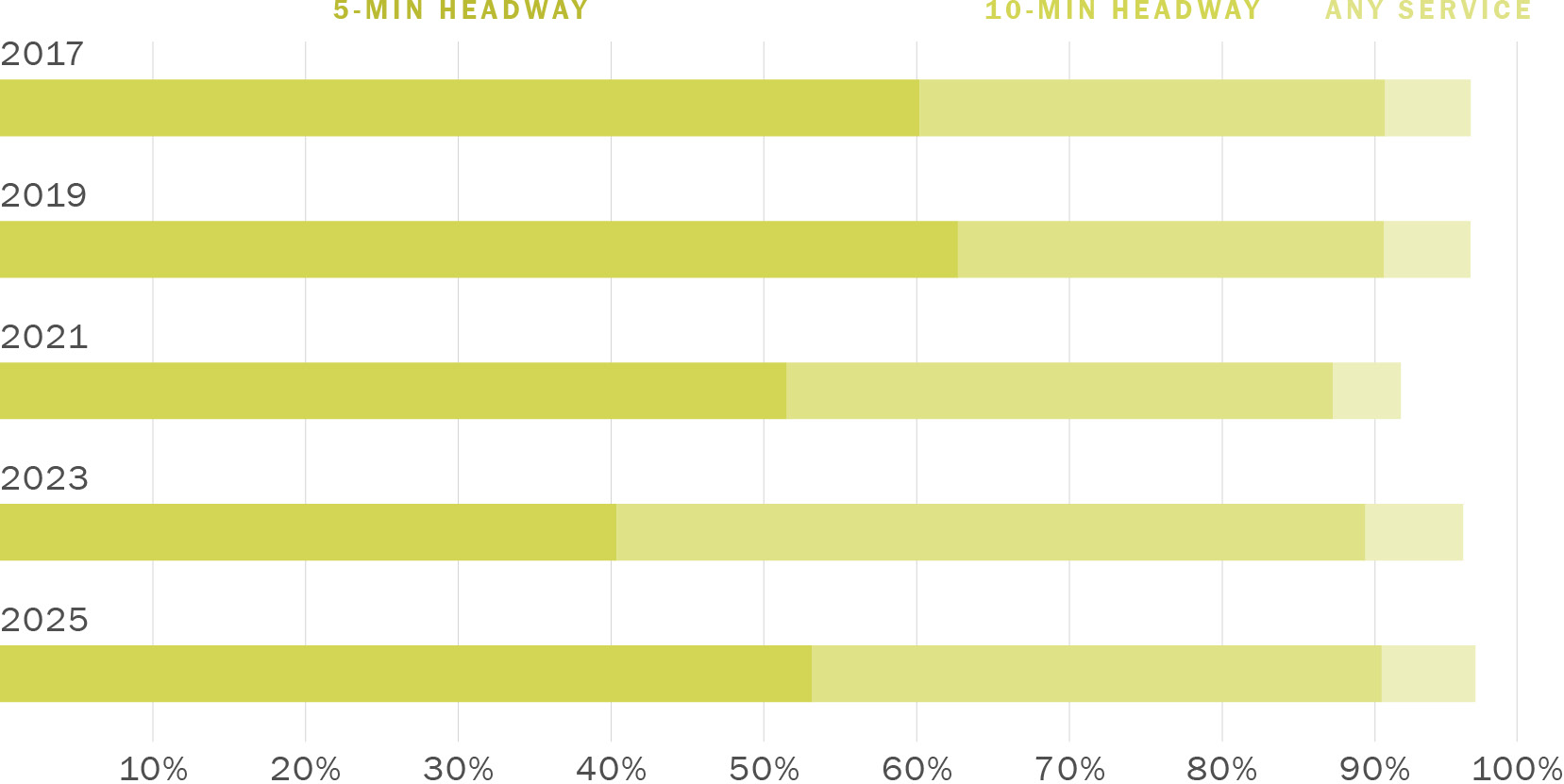

The transit coverage metric reports the percent of San Francisco’s total population and total jobs that are within a five-minute walk of Muni transit service. Since 2023, more than 95% of San Francisco residents live within a five-minute walk of Muni service. Moreover, the share of the population within a five-minute walk of a Muni route with a five-minute headway increased from 27% in 2023 to 29% in 2025 for the AM Peak and from 20% in 2023 to 27% in 2025 for the PM Peak, though this is still lower than the pre-COVID population share within a five-minute walk of a Muni route with a five-minute headway (Figure 0-22 and Figure 0-23). Transit coverage in terms of jobs for both the AM Peak and PM Peak periods show trends similar to those observed in population transit coverage.

Download chart data (CSV)

Download chart data (CSV)

What are we doing to manage congestion?

The Transportation Authority is analyzing current conditions and conducting long-range planning to manage congestion. The Downtown Travel Study analyzed post-COVID residential travel trends (March 2025) and the countywide transportation plan update is occurring through the San Francisco Transportation Plan 2050+ study process. Planning, funding, project delivery and policy research efforts are described further below:

Travel Demand Management (TDM)

The San Francisco Transportation Plan 2050 (SFTP2050) recommends TDM to maximize our countywide infrastructure investment priorities and to reduce congestion by shifting more trips from driving alone to walking, bicycling/rolling, transit, or carpooling. TDM may include policies, low-cost capital improvements, regulations (e.g., requirements on new development), and programs (e.g., information/outreach) designed to facilitate the use of sustainable transportation options.

San Francisco has identified a travel demand management (TDM) policy framework, strategy, and programs to systematically shift how, when, and where people travel, as documented in the 2017 San Francisco TDM Strategy. The Transportation Authority, in partnership with SFMTA and other local and regional agencies involved in TDM, is revising the 2017 TDM Strategy for the post-COVID era. This revision will build off of the Travel Demand Management (TDM) Market Analysis project that SFCTA is currently leading.

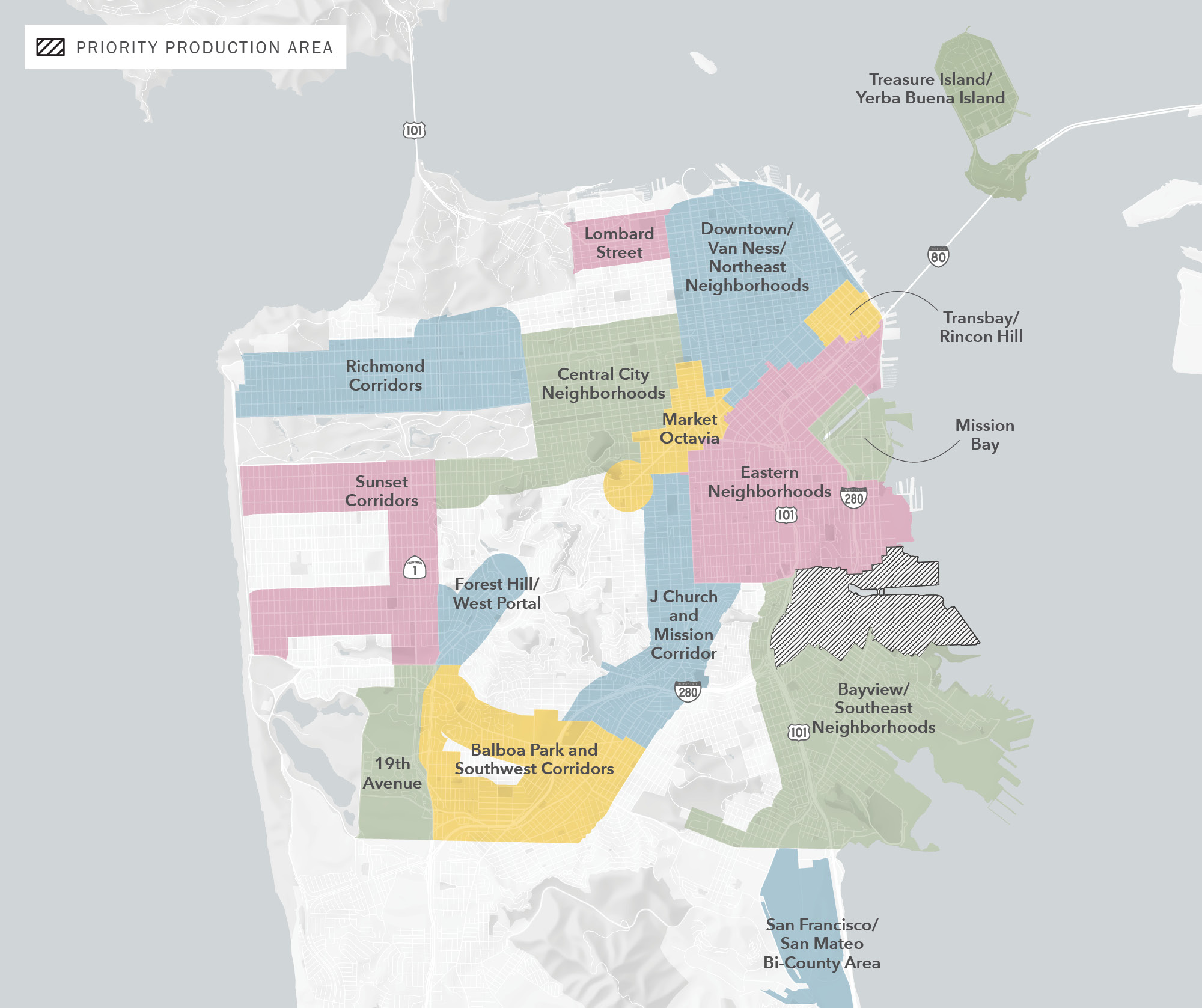

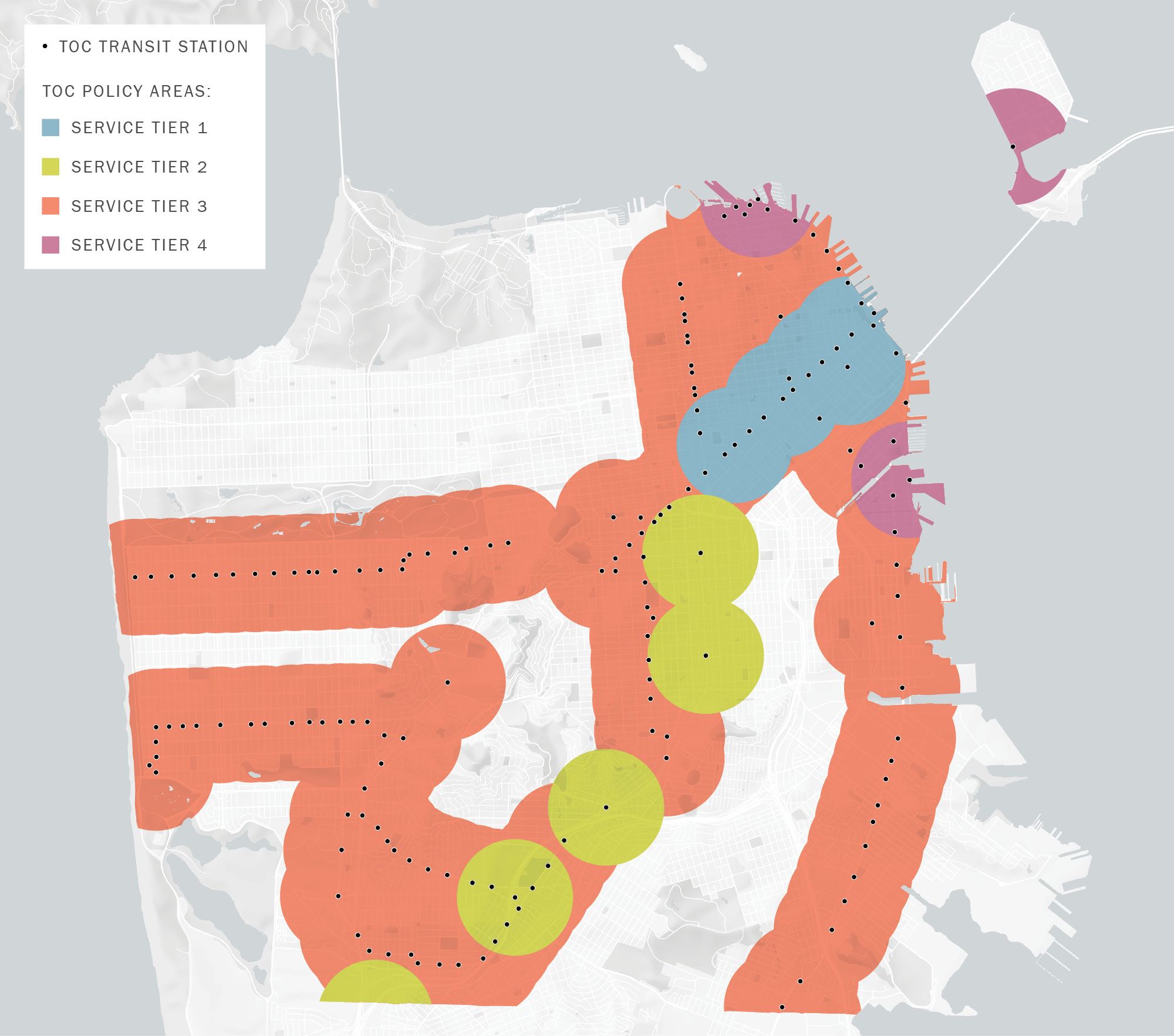

As the Treasure Island Mobility Management Agency, the Transportation Authority is leading a comprehensive mobility management program that encompasses new transit service and robust transportation demand management programs. Furthermore, San Francisco is encouraging efficient land use planning by supporting development at higher densities in areas that are mixed-use (closer to jobs and retail) and are well served by transit. Plan Bay Area 2050 identifies Priority Development Areas (PDAs) where densities and transit levels can more readily support transit-oriented development.

Planning Projects

From 2016 – 2022, Connect SF was a multiagency collaborative process to build an effective, safe, equitable, and sustainable transportation system for San Francisco’s future. ConnectSF developed a long-range vision for 2065 that serves as the underpinning of Plan Bay Area 2050+ and SFTP 2050+. The Transportation Authority is also coordinating with numerous local, regional state and Federal agencies and with the private sector to address congestion. Key initiatives include:

- San Francisco Transportation Plan, currently undergoing a minor update expected 2026 (SFTP+)

- San Francisco Freeway Management Study (Phase 1 anticipated Summer 2026)

- Treasure Island Mobility Management Program

- Inner Sunset Transportation Study

- D2 Safety Study

- D4 Microtransit Study and Business Plan

- Bayview Caltrain Station Location Study

- Westside Network Study

- Brotherhood Way Safety and Circulation Plan

- Geary/19th Subway and Regional Connections Study

Funding and Delivering Projects

The Transportation Authority is addressing near- and long-term transportation needs for San Francisco by funding projects and programs — mainly capital infrastructure, through grant programs such as the Proposition L transportation sales tax, Proposition AA vehicle registration fee, Prop D Traffic Congestion Mitigation Tax (TNC Tax), Transportation Fund for Clean Air, and One Bay Area Grants (OBAG) programs, as well as coordinating with other local and regional agencies to apply for State and Federal funding to match local investments. Below are a few signature projects supported with Transportation Authority funds:

- Muni New and Renovated Vehicles

- The Portal / Caltrain Downtown Extension to Salesforce Transit Center

- Peninsula Corridor Electrification Project

- BART and Muni core capacity

- Vision Zero / Safety Projects

The Transportation Authority is also overseeing and leading the delivery of key projects, many of which support infill transit-oriented development, including serving as co-sponsor or lead agency for the construction of:

- Bay Skyway/Yerba Buena Island Multi-Use Pathway (lead)

- I-280 Southbound Ocean Avenue Off-Ramp Realignment (lead)

- Hillcrest Road Improvement Project (lead)

- West Side Bridges Retrofit (lead)

Autonomous Vehicles

While the CMP’s focus is primarily on monitoring multimodal system performance and managing current congestion, the City must also plan for future system performance and congestion. San Francisco is a dense urban environment, and a critical challenge is how we manage our limited public right-of-way in order to maximize the movement of people and goods. While technologies such as web conferencing enabled increased levels of working from home which may help reduce peak period congestion, other emerging technologies and mobility services may lead to increased congestion.

Over the past few years, the California Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) have approved numerous permits for autonomous vehicles (AVs) to operate on San Francisco roadways, culminating in an August 2023 decision by the CPUC to allow two AV companies (Waymo and Cruise) to offer fared ride hailing services at all times of day across the entire City, with no limits on fleet size, not unlike the ride hailing services provided by Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) such as Uber and Lyft. Prior work by the Transportation Authority documented that ride hailing was responsible for approximately 50% of the increase in congestion between 2010 and 2016. As AVs scale up and become more widely deployed, it is reasonable to expect that AV ridehail services may similarly be generating vehicle miles traveled on San Francisco’s roadways and contributing to congestion in San Francisco.

The Transportation Authority, in coordination with other San Francisco agencies, have identified the need for the CPUC to move towards a performance-based incremental permitting of AVs. Such performance-based regulation, as well as the Transportation Authority’s responsibility to monitor transportation system performance and the potential impact of TNCs and AVs on congestion and other performance metrics such as safety, requires that agencies such as the CPUC and the Transportation Authority have access to useful, timely, reliable, and unredacted data. Unfortunately, at present, the data reported to the DMV and CPUC under a variety of testing, pilot, deployment, drivered and driverless permits is too incomplete, inconsistent, and redacted to provide policy-makers with the knowledge they need to make informed decisions. Without reliable data, it is challenging to facilitate safe, equitable, and sustainable integration of AVs into the City’s transportation ecosystem.

What are we doing to improve safety?

The City and County of San Francisco adopted Vision Zero as a policy in 2014, committing to build better and safer streets, educate the public on traffic safety, enforce traffic laws, and adopt policy changes that save lives. The goal is to eliminate traffic fatalities and to create a culture that prioritizes traffic safety. In July 2025, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed the San Francisco Street Safety Act, re-affirming the city’s commitments and describing a shared work program toward achievement of city goals. The Transportation Authority and the Controller’s Office were charged with monitoring these actions and assessing progress on an annual basis.

A significant portion of San Francisco’s arterial CMP network overlaps with its Vision Zero High Injury Network. In 2025, the Board of Supervisors adopted the San Francisco Street Safety Act, directing a multiagency coordinated approach to ending severe and fatal traffic crashes. The act directs agencies to pursue strategies to identify and implement infrastructure improvements, improve traffic enforcement, pursue electronic enforcement technologies like red light and speed cameras, establish procedures to implement solutions more efficiently, and prioritize solutions where they are needed most.

The Transportation Authority advances safety by:

- Integrating safety into planning work

- Prioritizing safety for funding programs, particularly for vulnerable and disadvantaged communities

- Advocating for policies and legislation that advance San Francisco’s safety goals

- Advocated for legislation enabling use of speed cameras

- Provided input on AV legislation and regulatory policies at state and federal level

- Recommend and implementing proven solutions

- Yerba Buena Island Ramps program

- Vision Zero ramps Phase 1, 2 and 3 (forthcoming)

Chapter 1

Background and Program Overview

KEY TOPICS

- CMP Background

- Legislative Requirements, Intent, and Application to San Francisco

- Congestion Management in San Francisco

1.1 Background

1.1.1 Purpose of the CMP

As the Congestion Management Agency (CMA) for San Francisco, the San Francisco County Transportation Authority (the Transportation Authority) is responsible for preparing a Congestion Management Program (CMP) update biennially. As mandated by state law, the purposes of the CMP are to:

- Define San Francisco’s performance measures for congestion management;

- Report congestion monitoring data for San Francisco county to the public and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC);

- Describe San Francisco’s congestion management strategies and efforts; and

- Outline the congestion management work program for the two upcoming fiscal years.

1.1.2 Organization and Approach

This document follows MTC’s Guidance for Consistency of Congestion Management Programs with the Regional Transportation Plan, per MTC Resolution 3000.

Each element required by the CMP legislation is discussed in a separate chapter. Each chapter describes the element’s context in San Francisco, the work plan, and implementation guidance. The Transportation Authority Board will adopt any revisions developed during the two upcoming fiscal years as amendments to the current cycle San Francisco CMP.

In preparing the CMP update, the Transportation Authority has consulted with the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) and other partner agencies to update policies and compile system performance data.

1.1.3 Origins and Intent of the CMP Legislation

CMP requirements were established in 1989 as part of a bi-partisan state legislative package, known as the Katz-Kopp-Baker-Campbell Transportation Blueprint for the Twenty-First Century (AB 471). These requirements became effective when voters approved Proposition 111 on June 5, 1990. AB 1963 (Katz) in September 1994 and AB 2419 (Bowler) in July 1996 further modified CMP law. The passage of AB 298 (Rainey), effective January 1, 1997, made the CMP exempt from the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). SB 1636 (Figueroa 2002) amended CMP requirements to allow local jurisdictions to designate Infill Opportunity Zones (IOZs). SB 743 (Steinberg 2013) further revises the definition of “IOZ” to generally encompass a larger area than that allowed in SB 1636.

The 1989 state legislation directs the regional agency (MTC) to not program any surface transportation program funds and congestion mitigation and air quality funds for a project in a local jurisdiction that has been found to be in nonconformance with a congestion management program unless the project is found to be of regional significance. The goal of the legislation is to strengthen and coordinate local transportation funding and land use decisions by requiring preparation of long-range countywide transportation every four years, and monitoring of local transportation conditions every two years.

The CMP legislation aims to increase the productivity of existing transportation infrastructure and encourage more efficient use of scarce new dollars for transportation investments, in order to effectively manage congestion, improve air quality, and ultimately allow continued development. To achieve this, the CMP law is based on five mandates:

- Require more coordination between federal, state, regional, and local agencies involved in the planning, programming, and delivery of transportation projects and services;

- Favor transportation investments that provide measurable and quick congestion relief;

- Link local land use decisions with their effect on the transportation system;

- Favor multimodal transportation solutions that improve air quality; and

- Emphasize local responsibility by requiring a Congestion Management Agency (CMA) in each urban county in the state.

1.2 Legislative Requirements, Intent, and Application to San Francisco

The Congestion Management Program is prepared pursuant to the requirements in California Government Code section 65088 – 65089.10. One of the main objectives of the CMP legislation is to foster coordination of local land use and transportation investment decisions at the county or subregional level. To ensure local involvement in this process the CMP law vests significant authority and responsibility in the Congestion Management Agencies (CMAs). CMAs therefore act as a policy forum and technical resource to guide and help coordinate local and regional congestion management efforts.

1.3 Congestion Management in San Francisco

1.3.1 Applicability of the Concept

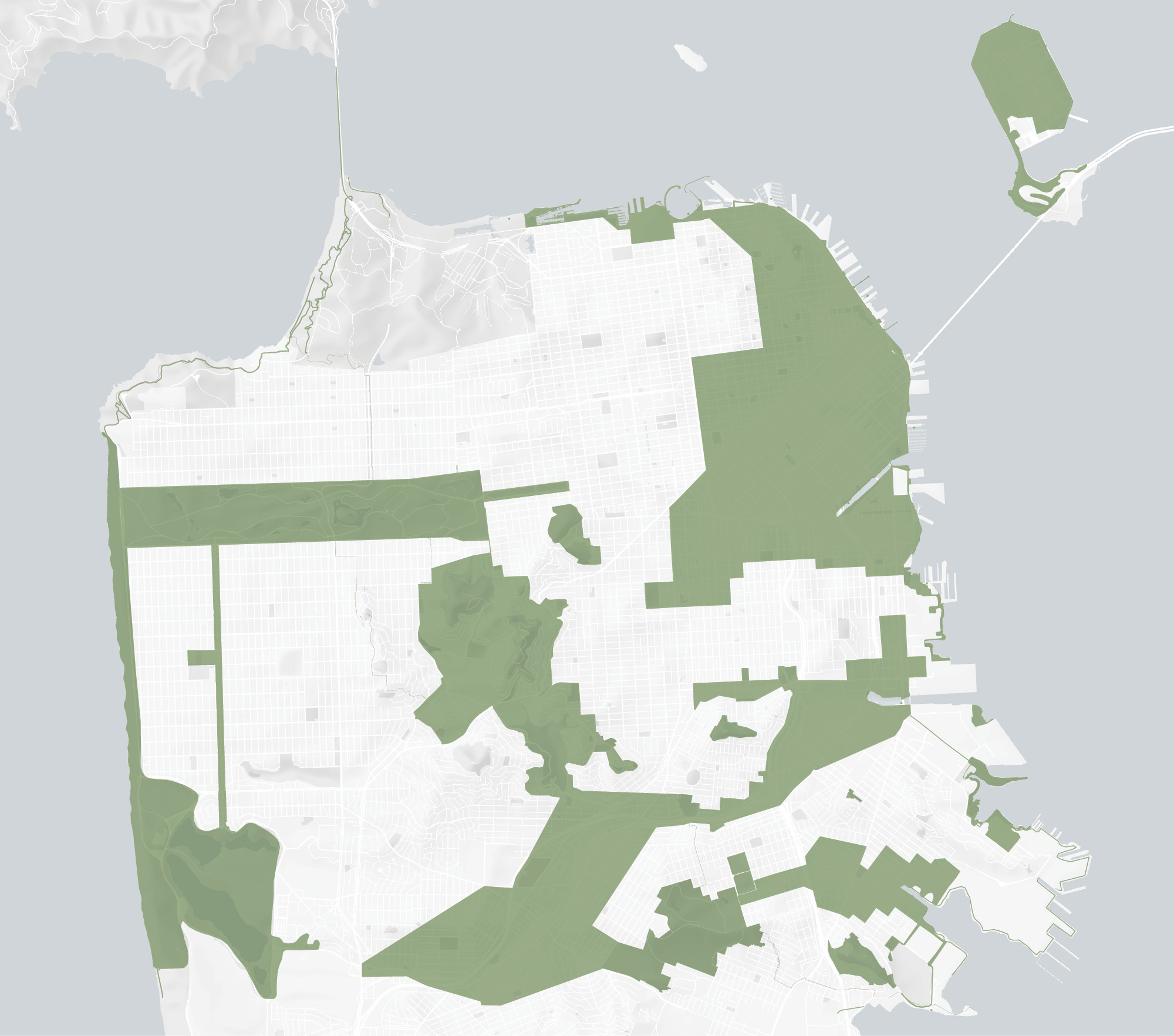

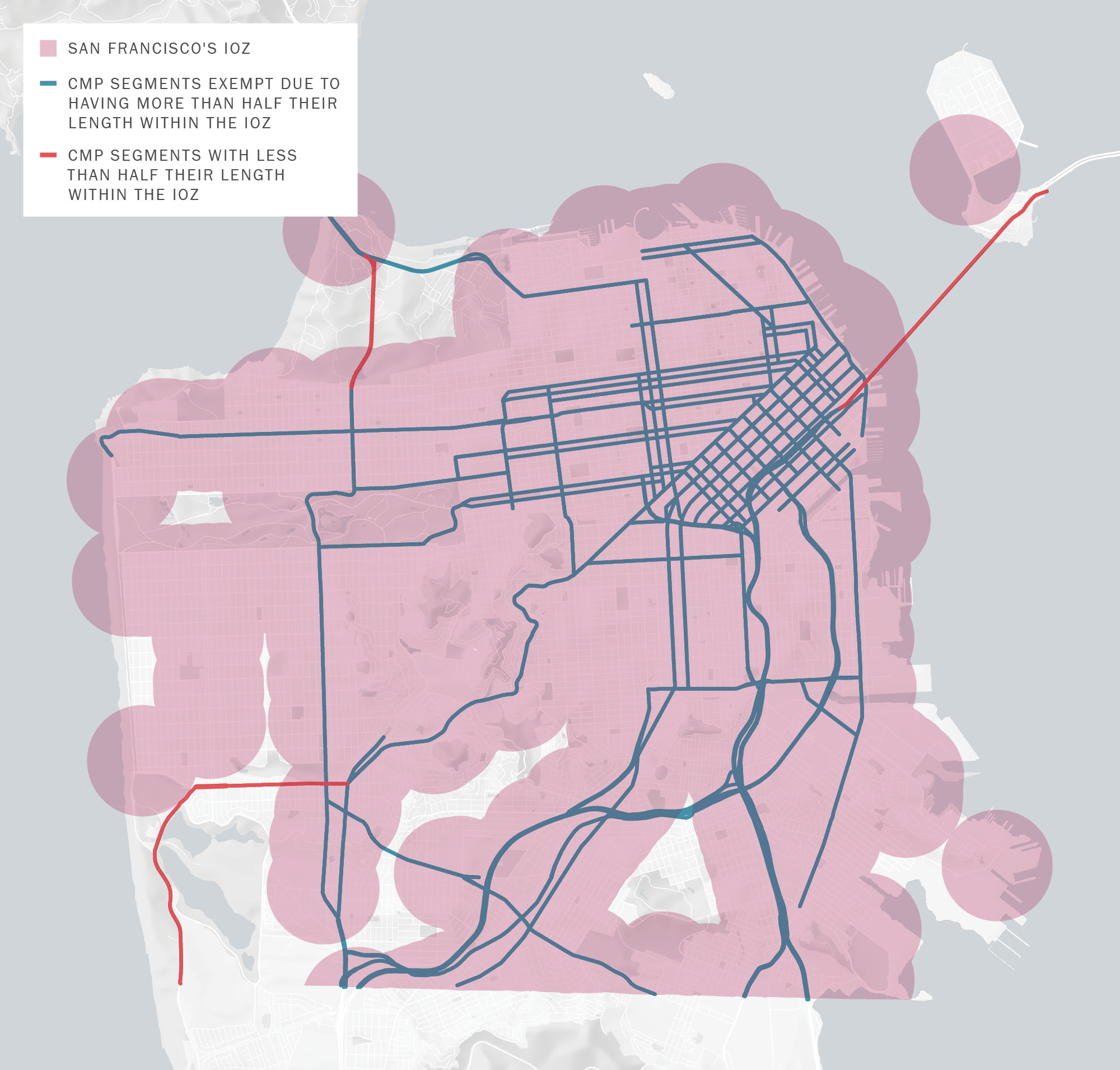

By statute, congestion management agencies must report on the roadway level of service (LOS) for its countywide network of regionally significant streets and highways (the Metropolitan Transportation System) outside of an infill opportunity zone (IOZ). However, SB 1636 enabled congestion management agencies to consider alternative metrics to LOS for measuring and mitigating roadway congestion within IOZs. To better align San Francisco’s CMP with its longstanding Transit First policy, San Francisco designated an IOZ in 2009 and, pursuant to SB 743 which expanded IOZ criteria, expanded the IOZ designation in 2024. Also pursuant to SB743, in 2016, the San Francisco Planning Commission formally replaced LOS with Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) as San Francisco’s measure of local traffic impacts under CEQA.

1.3.2 Mandated Program Components

The following statutory requirements of CMP legislation are mandated for all urban counties in the state:

- A CMP updated biennially. The CMP must contain the following:

- A designated CMP roadway network

- A multimodal performance element that includes traffic level-of-service (LOS) standards and a methodology for monitoring LOS on the designated CMP roadway network, as well as transit service standards

- A travel demand element that promotes alternative transportation methods

- A land use impact analysis methodology

- A seven-year multimodal Capital Improvement Program (CIP);

- A common database and method to analyze impacts of local land use decisions on the CMP network; and

- A designated CMA for the county.

1.3.3 Key Changes from the 2023 CMP

The following sections highlight the most significant updates included in the 2025 CMP.

Infill Opportunity Zone (IOZ) update: The Board of Supervisors passed a resolution in September 2024 updating the area designated as an IOZ in San Francisco to an area that is on the whole larger than the previously designated (in 2009) IOZ. This IOZ update is reflected throughout the report.

- Chapter 4: This chapter presents the latest multimodal performance monitoring data along with updated long-term trends.

- Chapter 5: The Transportation Demand Management (TDM) Element has been updated to reflect recent changes to planning code requirements, advancements to San Francisco TDM strategies, including new policies requiring TDM measures.

- Chapter 7: This chapter reflects amendments made to the CIP.

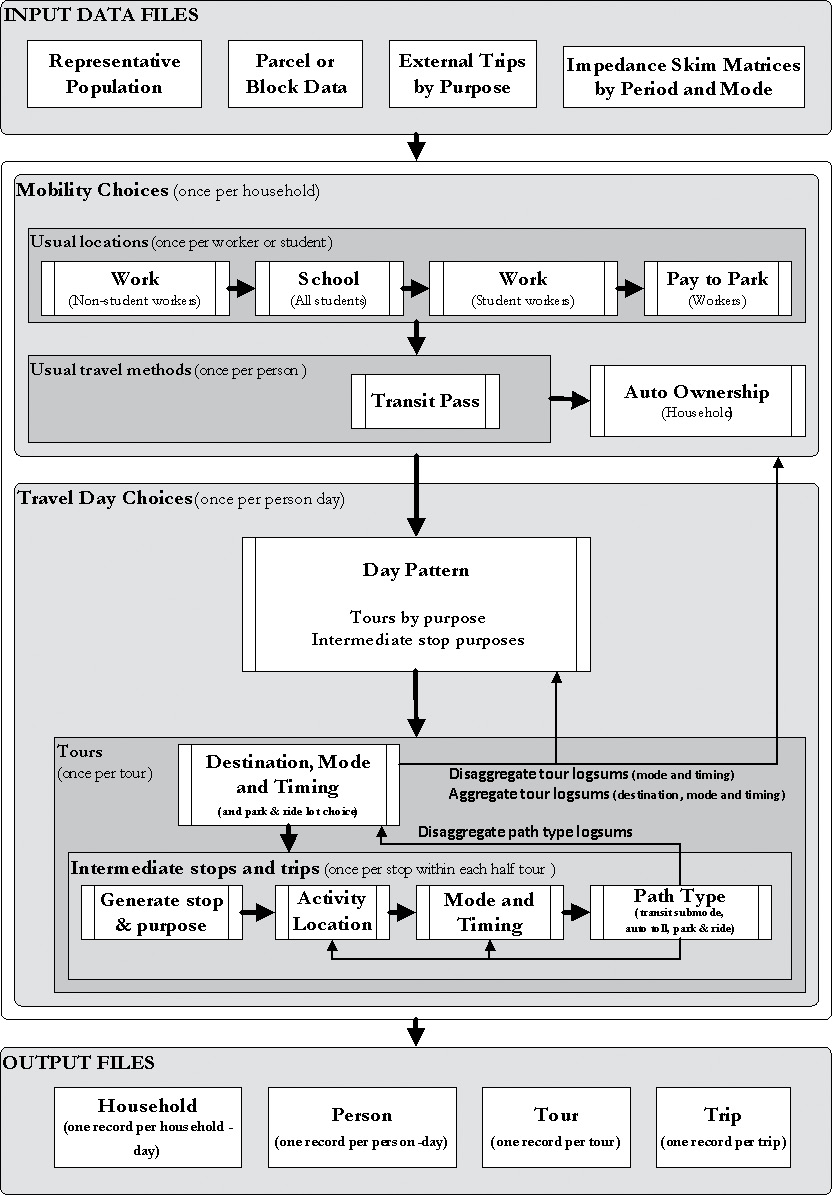

- Chapter 8: The Transportation Authority’s San Francisco Travel Demand Forecasting Model has undergone improvements since 2023, which are discussed in this chapter.

- Appendices: Posted former appendices for CMP Roadway Network Segmentation and Changes, Infill Opportunity Zone Resolution, and Deficiency Plans directly to the Transportation Authority's CMP reports & documents webpage and removed from the report. Replaced former appendix Transit Frequency and Coverage Service Levels with links to transit agency standards in the Bibliography.

1.3.4 Public Input

The Draft 2025 San Francisco CMP has undergone public review at the November 19, 2025 meeting of the Transportation Authority’s Citizens Advisory Committee. The Transportation Authority Board also approved the 2025 CMP on December 9 and 16, 2025.

Chapter 2

Congestion Management Agency Role & Responsibilities

KEY TOPICS

- San Francisco County Transportation Authority

2.1 The San Francisco County Transportation Authority

2.1.1 Designation and Composition

On November 6, 1990, the Board of Supervisors designated the San Francisco County Transportation Authority (the Transportation Authority) as the CMA for the County. The Transportation Authority Board of Commissioners consists of the eleven members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, acting as Transportation Authority Commissioners.

2.1.2 Roles and Responsibilities

The Transportation Authority is a special-purpose government agency, created on November 7, 1989, when San Francisco voters passed Proposition B. Proposition B increased the local sales tax by ½ cent for a period of 20 years, to fund San Francisco transportation projects and services. Prop B was superseded by Prop K in 2003, which is in turn superseded by Prop L in 2022, which extends the ½ cent sales tax for 30 years. The Transportation Authority administers, prioritizes, and programs Proposition L revenues. These revenues also leverage large amounts of State and Federal funds for transportation investments in San Francisco.

On November 2, 2010 San Francisco voters approved Proposition AA, authorizing collection of an additional $10 fee annually on motor vehicles registered in San Francisco and approving an Expenditure Plan for the new funds. The fee funds local street repair, improvements to pedestrian and bicycle conditions, and public transit enhancements. As with Prop L, the Transportation Authority administers, prioritizes, and programs Prop AA funds.

The Proposition D Traffic Congestion Mitigation Tax was passed by San Francisco voters in November 2019. The measure is a surcharge on commercial ride-hail trips, including those provided by autonomous vehicles, that originate in San Francisco, for the portion of the trip within the city. The TNC Tax program seeks to mitigate the effects of increased congestion due to ride-hail trips by directing funds to deliver improvements to transit reliability and safety on San Francisco’s roadways.

In its capacity as the CMA for San Francisco, the Transportation Authority has primary responsibilities in the following areas:

- Develop and adopt the biennial CMP and related implementation guidance;

- Monitor City agencies’ compliance with CMP requirements;

- Program Federal, State, and regional transportation funds;

- Review the programming of all transportation funds for San Francisco;

- Provide policy input into the regional transportation planning and programming process; and

- Develop and periodically update the long-range countywide transportation plan, the San Francisco Transportation Plan (SFTP), for San Francisco.

The Transportation Authority’s dual responsibilities — administering the local half-cent transportation sales tax and prioritizing and programming of State and Federal funds through the CMP and SFTP process — are an opportunity to coordinate San Francisco’s transportation planning decisions and optimize the City’s investments in transportation infrastructure and services. The SFTP links transportation objectives and policies to a specific list of transportation investments, prioritized across a long-range planning horizon. The CMP’s seven-year CIP and the Transportation Authority’s Prop L Five-Year Prioritization Programs serve as the main implementation tools for the San Francisco Transportation Plan.

As the CMA, the Transportation Authority serves as the lead coordinator for San Francisco involvement in the regional process to develop a Sustainable Communities Strategy (SCS) and update the Regional Transportation Plan (RTP). Plan Bay Area 2050, which integrates the SCS and RTP into a single regional plan, was recently updated and adopted by MTC and ABAG in October 2021 and amended in November 2024. As required by SB 375 (Steinberg), passed in 2008, Plan Bay Area integrates long-range land use, housing, and transportation planning in the region to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from motor vehicles. An update to the plan, Plan Bay Area 2050+, is expected to be considered for adoption in 2026.

In 2011, the Transportation Authority deepened our role in congestion management on Treasure Island by being designated as the Treasure Island Mobility Management Agency (TIMMA). Subsequent resolutions tasked the Transportation Authority with advancing agency formation documents, planning, and tolling.

In addition, acting as the CMA, the Transportation Authority plays a key role in reviewing and supporting transportation analyses for major local transportation projects and land use policies that may affect the performance of the transportation system.

2.1.3 Relationship to City Agencies

State law mandates that the Transportation Authority, acting as CMA, biennially determines if the City is in conformance with the adopted Congestion Management Program. A finding of non-conformance has potentially significant consequences for transportation funding in the City. Also, according to state law, it is the City’s responsibility to ensure that transportation projects, programs, and services are put in place, through its implementing departments, to maintain conformance with the CMP.

In fulfilling its CMA mandate, the Transportation Authority must assess City departments’ transportation-related actions at least biennially relative to their congestion management impacts. In doing this, maximizing coordination with the City departments responsible for planning and implementation of transportation actions, so that such actions may be evaluated for congestion management impacts before they are put in place.

2.1.4 Relationship to Regional Planning/Programming Agencies

As the Congestion Management Agency for San Francisco, the Transportation Authority plays a key sub-regional planning and funding role with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), the Bay Area’s regional transportation planning agency, and with the Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD), the agency responsible for implementation and monitoring of the region’s Clean Air Plan. The Transportation Authority coordinates local input into MTC’s Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) through the development of the San Francisco Transportation Plan, which establishes the overall vision and priorities for long-range transportation development and funding for San Francisco, and through San Francisco’s portion of the Regional Transportation Improvement Program (RTIP). In these ways, San Francisco influences the vision and goals for transportation and land use planning in the Bay Area.

Chapter 3

CMP-Designated Roadway Network

KEY TOPICS

- Legislative Requirements

- San Francisco CMP Roadways

3.1 Legislative Requirements

California Government Code Section 65089(b)(1)(A) requires that performance standards be established for a system of highways and roadways designated by the agency, and that this designated Congestion Management Network include at least all state highways and principal arterials. No highway or roadway designated as part of the system may be removed from the system. The statutes do not define ‘principal arterial.’

The statutes also refer to regional transportation systems as part of the required land use impacts analysis program, California Government Code Section 65089(b)(4). In 1991, the Bay Area’s Congestion Management Agencies (CMAs) developed Congestion Management Program (CMP) networks in coordination with MTC’s Metropolitan Transportation System (MTS). The MTS network, which includes both highways and transit services, was subsequently designated as the Congestion Management System, as required by the federal Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA) of 1991. The MTC contracted with the congestion management agencies in the Bay Area to help develop the MTS and to use the CMPs to link land use decisions to the MTS.

3.2 San Francisco CMP Roadways

CMP legislation requires that all state highways (including freeways) and principal arterials are included in the CMP network. The network must be useful to track the transportation impacts of land development decisions, as well as to assess the congestion management implications of proposed transportation projects. San Francisco’s network therefore includes numerous local thoroughfares since most urban traffic occurs on city arterials (rather than on the freeways). The next sections document the network selection criteria and process used in the initial San Francisco CMP in 1991 and describe the current network.

3.2.1 Selection Criteria

Consistent with State requirements, the San Francisco CMP roadway network includes all freeways and state highways, as well as principal arterials. San Francisco has defined principal arterials as the Major Arterials designated in the Transportation Element of the City’s General Plan, defined as follows:

“cross-town thoroughfares whose primary function is to link districts within the city and to distribute traffic from and to the freeways; these are routes generally of citywide significance; of varying capacity depending on the travel demand for the specific direction and adjacent land uses.”

Several additional arterials — Market Street, Mission Street, Sutter Street, and West Portal — are also included in the CMP roadway network. These streets experience significant conflicts between auto traffic and transit service.

3.2.2 Segmentation Method

The 1993 CMP documented the criteria used in 1991 to segment the CMP roadway network in San Francisco, including freeway facilities (see the CMP Roadway Network Segmentation and Changes document on the Transportation Authority’s CMP reports & documents page). The following five criteria determined segment limits for the city arterials in the CMP: predominant development patterns (e.g., number of driveways, institutional uses); changes in speed limits; major cross streets; significant changes in traffic volumes; and freeway ramps. These criteria are generally recognized as significant in explaining the operating profile of a roadway.

For freeway facilities the segmentation criteria are simpler. They include major interchange on and off ramps, and points where two freeway facilities merge or bifurcate.

3.2.3 Current Network

The complete CMP roadway network for San Francisco consists of 233 directional miles on both arterials and freeways.

|

ROADWAY TYPE |

TOTAL DIRECTIONAL MILES |

|---|---|

|

Arterial |

198.4 |

|

Freeway |

34.9 |

|

Total |

233.3 |

Performance monitoring was conducted in the current CMP cycle for the entire CMP network.

A complete list and description of all arterial and freeway segments in the CMP network can be found in the CMP Roadway Network Segmentation and Changes document on the Transportation Authority’s CMP reports & documents page.

3.2.4 Network Changes

State law prohibits the removal of roadway facilities from the initially designated CMP network (unless facilities are physically removed from the transportation system, such as the Embarcadero Freeway). New facilities may be added to the CMP network without restrictions, subject to the established criteria for inclusion. No network segmentation changes were made in the current CMP cycle. The CMP Roadway Network Segmentation and Changes document on the Transportation Authority’s CMP reports & documents page lists all CMP arterials where segmentation changes have been made since 1991, including a technical justification.

From time to time the Transportation Authority may also monitor additional segments that are not part of the official CMP network. These do not constitute official changes to the CMP network but may be included to support current planning and system management efforts. The Transportation Authority has not monitored any additional segments in the current CMP cycle.

Download map data (GeoPackage)

Chapter 4

Multimodal Performance

KEY TOPICS

- Legislative Requirements

- Legislative Intent and Application to San Francisco

- Applications of Multimodal Performance Measures

- Legislatively Required Performance Measures (Auto LOS and Transit)

- Local Performance Measures (Transit, Biking, and Walking)

- Work Program Items

This chapter presents the Congestion Management Program (CMP) multimodal performance results, including analyses of traffic congestion, transit, and non-motorized performance measures. It combines the traffic Level of Service (LOS) and multimodal performance elements required under state CMP legislation, reflecting the legislation’s requirement that LOS be included as one of several multimodal performance measures. This approach is also consistent with San Francisco’s urban multimodal environment. Vehicular traffic congestion remains an important metric of transportation performance in San Francisco, but the City and County’s Transit First policy and emphasis on accessibility place higher priority on the performance of alternative modes including transit, biking, and walking than on private vehicle speeds.

4.1 Legislative Requirements

4.1.1 LOS Monitoring

The California Government Code requires that San Francisco use automobile LOS standards to measure the performance of the CMP roadway network, but permits Congestion Management Agencies (CMAs) a choice among the following methodologies for measuring LOS:

- Transportation Research Board Circular 212 (TRC 212);

- Transportation Research Board’s Special Report 209: Highway Capacity Manual (HCM); or

- A uniform methodology adopted by the CMA that is consistent with the Highway Capacity Manual

The CMA is required to biennially determine the City’s conformance with the CMP, including attainment of LOS standards.

In accordance with Congestion Management legislation, county and city governments are required to show that CMP route segments within their jurisdiction are operating at or above the CMP traffic LOS standard for all segments outside of any designated Infill Opportunity Zone (IOZ). CMP route segments located within an IOZ are exempt from the minimum LOS standards and deficiency plan requirements mandated elsewhere by the CMP legislation. (California Government Code, Section 65089(b)(1)(B)) See Chapter 6 for a more detailed description and a map of San Francisco’s IOZ.

4.1.2 Multimodal Performance Monitoring

The CMP legislation also requires a multimodal performance element. AB 1963 in 1994 requires that the CMP shall include “[a] performance element that includes performance measures to evaluate current and future multimodal system performance for the movement of people and goods,” and identifies performance measure requirements.

4.2 Legislative Intent and Application to San Francisco

The original CMP legislation defined performance narrowly as roadway LOS. The amendments to the CMP legislation acknowledged the need for diversified solutions to complex transportation problems in urban areas, and the inadvisability of tackling them with just one mode. Current performance element requirements recognize that the transportation system performance monitoring should be multimodal: automobile, transit, bicycling, walking, and emerging modes such as micromobility, or ride share.

According to the CMP legislation, deficiencies are identified only on the roadway system. The LOS scale focuses only on automobile travel. It does not take into account the person throughput capacity of a roadway, nor does it account for other vital performance measures of roadways such as safety. A city arterial may carry the maximum number of automobiles at an acceptable speed, but if each vehicle carries only the driver, then the throughput of the facility is suboptimal. San Francisco therefore includes performance standards and measurements that evaluate more aspects of the City’s multimodal transportation network. San Francisco’s high transit, walking, and biking mode shares and extensive non-auto mode networks mean that the city benefits from a multimodal approach to system performance monitoring.

Consistent with State law, this report distinguishes between two categories of performance measures. Legislatively required measures include roadway LOS plus three transit service performance measures: routing, frequency, and inter-operator service coordination. These are the elements of congestion and multimodal performance measurement that are explicitly required by State congestion management statutes. San Francisco’s CMP includes one additional roadway performance measure called the Buffer Time Index (BTI), which indicates roadway speed reliability. Section 4.4 provides details on all these metrics.

Local performance measures include multimodal metrics that are not used for determination of CMP conformance under State legislation but reflect performance goals for non-automobile modes in San Francisco. The local measures are used for planning purposes and to track trends over time. Transit measures included in this CMP include transit speeds, transit-to-auto speed ratios, transit speed reliability (variability), and transit accessibility, which tracks the proportion of population and jobs that are within a five-minute walk to a given frequency of transit service. Non-motorized metrics include multimodal volumes, bicycle network completeness, and injury or fatal collisions involving people walking or biking. These measures are discussed in further detail in Section 4.5.

4.3 Applications of Multimodal Performance Measures

State law requires that link (roadway) LOS be used for determining CMP conformance and conducting deficiency planning, except within a designated Infill Opportunity Zone. Multimodal performance measures will be used for the following purposes:

- CMP conformance determinations

- CIP amendments

- Deficiency plans

- Land use impacts analysis

4.4 Legislatively Required Performance Measures

4.4.1 Roadway Speeds Monitoring

The CMP legislation defines roadway performance primarily by using the LOS traffic engineering concept to evaluate operating conditions on a roadway. LOS describes operating conditions on a scale of A to F, with “A” describing free flow, and “F” describing bumper-to-bumper conditions. The CMP-mandated traffic LOS standard for San Francisco was established at E in the initial (1991) CMP network. Facilities that were already operating at LOS F at the time of baseline monitoring, conducted to develop the first CMP in 1991, are legislatively exempt from the LOS standard. In addition, because much of San Francisco is in an Infill Opportunity Zone, most CMP segments in San Francisco are exempt from minimum LOS standards. However, continued monitoring of automobile LOS is useful for a variety of reasons. As the most extensive historical dataset available, LOS allows for the monitoring of traffic conditions over a long period of time. In addition to LOS, travel time reliability is an important measure of roadway congestion. With travelers experiencing a broad range of conditions from day to day, it is not sufficient to understand congestion just in terms of “average” or “typical” conditions (as measured by LOS). The Buffer Time Index (BTI), calculated as the percent of average additional travel time that the travelers need to budget so that they have a 95% chance of arriving on time, was introduced in the CMP 2021 to measure roadway reliability. In other words, it is the extra time needed if one does not want to be late more than once a month.

Congestion is also an important factor affecting the performance of surface-running transit service, especially for transit operating in mixed traffic. Finally, ongoing monitoring of both automobile and transit speeds within the same corridor facilitates the assessment of relative modal performance.

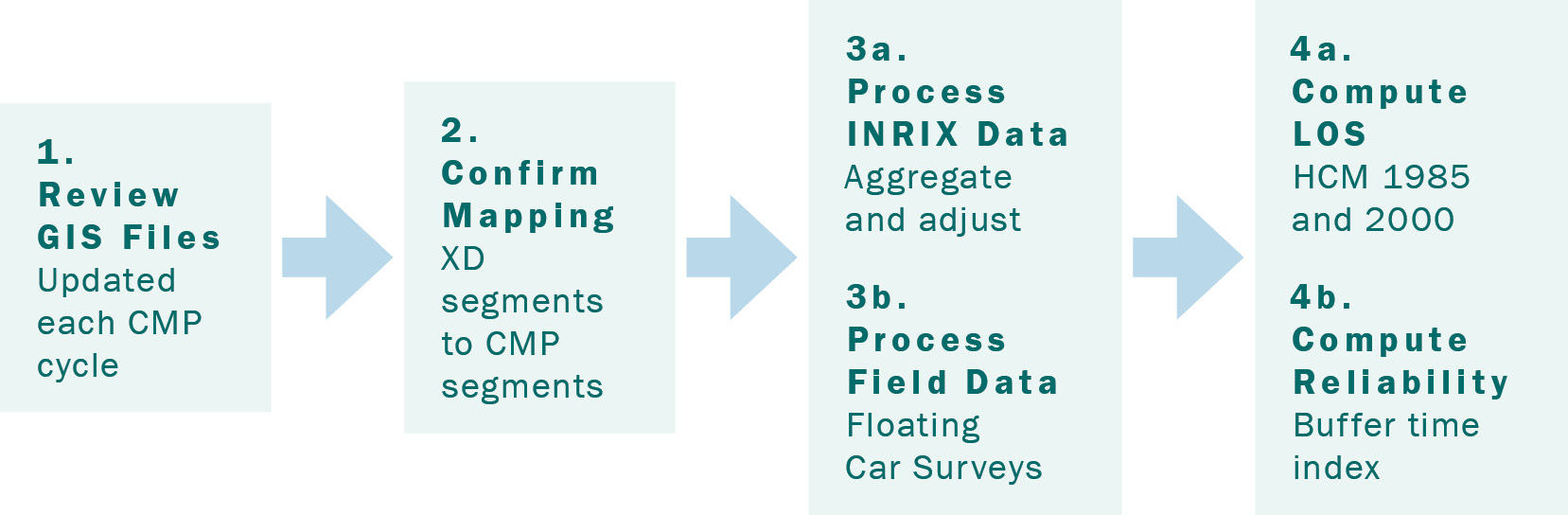

Monitoring Approach

The Transportation Authority uses commercial data from INRIX, which combines several real-time GPS monitoring sources with data from highway performance monitoring systems, as the primary source for speed and LOS calculations. INRIX data is supplemented with floating car data where INRIX data is not available. The INRIX and floating car data were collected in April and May 2025, which is the typical CMP monitoring period for San Francisco. The Buffer Time Index (BTI) for travel time reliability was calculated for CMP segments for which INRIX data were available (244 out of 245 segments). This is because BTI calculation involves deriving the distribution of speeds and travel times during the monitoring period and determining the 95th percentile values. This distribution cannot be calculated for the limited subset of segments for which only floating car run data were available. The methodology and results of the LOS Monitoring effort are detailed in Appendix 1.

Fall 2023 Data Anomaly and Change to Methodology

Traffic speeds vary seasonally, with lower speeds in the spring and fall, and higher speeds in the summer and winter during holidays and school closures. The CMP accounts for this seasonality by monitoring speeds in the same months, April and May, of each year. Speeds during 2020 and 2021 followed unique patterns due to the Covid 19 pandemic, but typical seasonality was evident again in 2022. From 2022 to 2025 so far, each year has exhibited normal seasonal trends. However, in August and September of 2023, when speeds typically decline from summer highs, INRIX data showed speeds continuing to increase. Staff could not identify any events that would explain a significant two-month long deviation in typical seasonal speed trends and believe there is an error in the underlying data or change in data processing methods, although INRIX has not confirmed this. After this unexplained increase in speeds data resumed typical seasonal patterns, although at elevated speeds. This resulted in higher peak period traffic speeds in 2025 than in 2023, which is an unintuitive trend that is not supported by contemporaneous arterial traffic counts in 2023 and 2025. As a result, the following analysis compares 2025 data to 2024 rather than data from the previous 2023 cycle, as would be typical.

Download chart data (CSV)

Summary of 2025 Roadway Monitoring Results

Table 4-1 and Table 4-2 presents the change in CMP network averageAverages are weighted by the length of each CMP segment. travel speeds (calculated as time-mean speed) and travel time reliability, between 2024 and 2025 for the AM Peak (7:00 – 9:00 a.m.) and PM Peak (4:30 – 6:30 p.m.) periods.

|

CATEGORY |

Peak Period |

Buffer Time Index |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 |

2025 |

Difference |

||

|

Arterial |

AM |

22% |

22% |

−0% |

|

PM |

21% |

20% |

−1% |

|

|

Freeway |

AM |

44% |

57% |

12% |

|

PM |

37% |

61% |

24% |

|

Roadway Speeds

In general, roadway speeds are lower during the PM Peak than in the AM Peak, conforming to long-time historical trends. Average speeds on the CMP network arterials have decreased since 2024 for both the AM Peak (−4%) and PM Peak (−6%). Average speeds on CMP network freeways also decreased in both the AM Peak and PM Peak (−4%).

Overall roadway speeds had been decreasing since 2011 until the COVID pandemic. Roadway speeds increased in 2021 during the COVID pandemic, then decreased between 2021 and 2023 as people began to return to pre-COVID pandemic activity levels. Speeds in both peak period on freeways and arterials declined from 2024 to 2025. (Figure 4-2).

A significant portion of San Francisco’s arterial CMP network overlaps with its Vision Zero High Injury Network. In 2025, the Board of Supervisors adopted the San Francisco Street Safety Act, directing a multiagency coordinated approach to ending severe and fatal traffic crashes. The act directs agencies to pursue strategies to identify and implement infrastructure improvements, improve traffic enforcement, pursue electronic enforcement technologies like red light and speed cameras, establish procedures to implement solutions more efficiently, and prioritize solutions where they are needed most. San Francisco has also introduced lower speed limits on a number of streets that are designated as “safety corridors”, many of which overlap with the CMP network. These changes work to improve the safety for all road users of San Francisco’s transportation system, and may be reflected in a drop in travel speeds on the CMP network.

Note: data collected April – May each year

Download chart data (CSV)

Arterial roadway speeds in the downtown core are historically lower than citywide average arterial speeds. In 2025, arterial speeds in the downtown core declined by −6% in the AM Peak and −7% in the PM Peak, a faster rate of decline than citywide arterial speeds (Figure 4-3), indicating relatively greater increases in congestion downtown as can be expected with economic activities returning after limited growth post-pandemic.

Note: Downtown Core in this figure is defined to include streets east of Franklin/Gough Streets, and north of the Central Freeway and Mission Creek. It also includes the streets immediately surrounding the Octavia Boulevard entrance/exit of the Central Freeway

Download chart data (CSV)

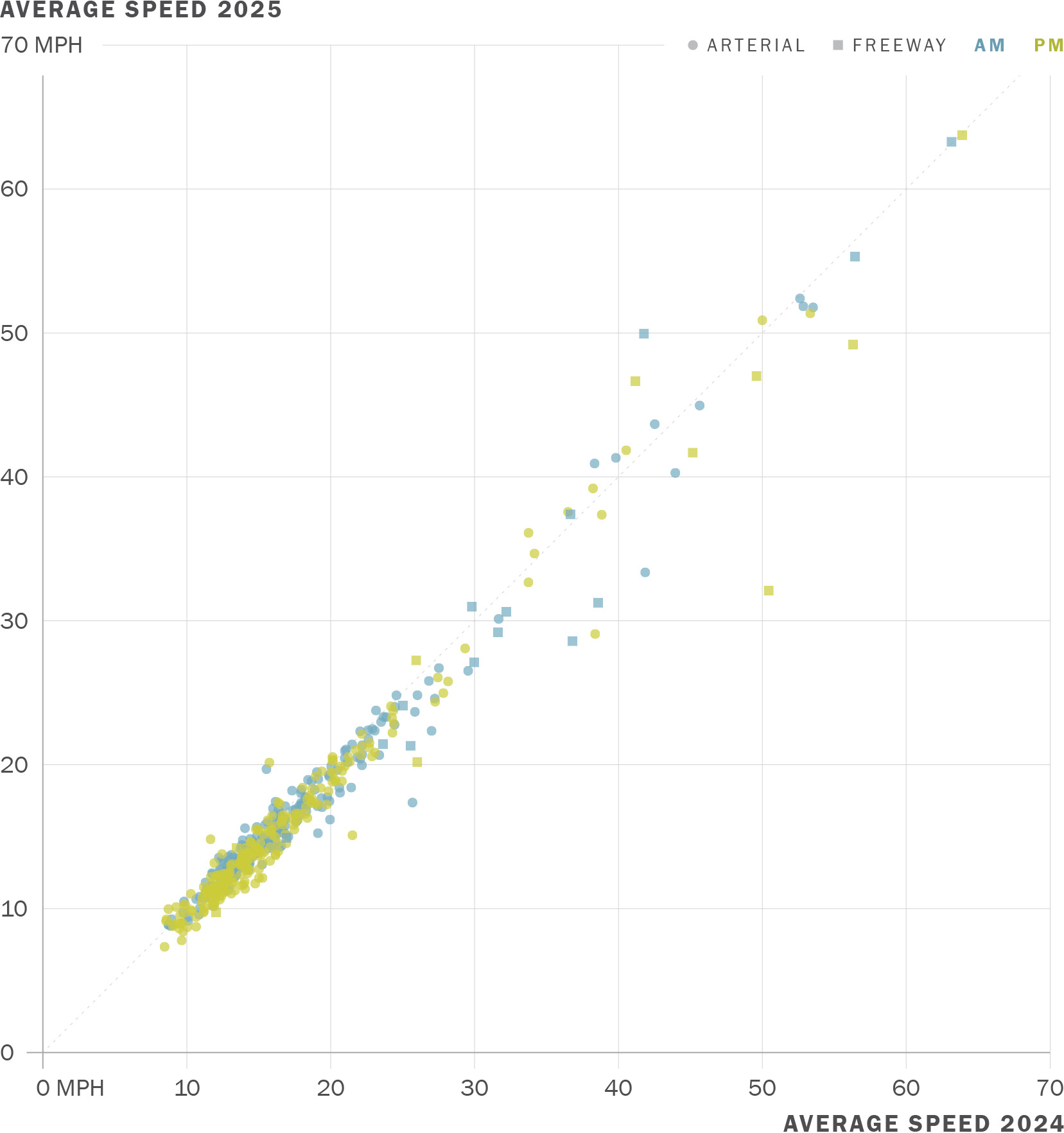

Figure 4-4 presents the change in CMP average speeds for each road segment between 2024 and 2025. The diagonal line from the lower left to the upper right means no change in speed has been observed, with points above (to the upper-left) / below (to the bottom-right) of the diagonal indicating speed increases/decreases respectively. Points clustered below and to the right of the diagonal line indicate that speeds have generally decreased from 2024 to 2025.

Download chart data (CSV)

Table 4-3 and Table 4-4 identify the segments that experienced the largest percentage decrease in speed since the previous CMP cycle.

Roadway Travel Time Reliability

In addition to speed and LOS, the Buffer Time Index (BTI) travel time reliability metric was derived for all CMP segments for which INRIX data were available, where a lower value of BTI indicates higher reliability. Between 2024 and 2025 reliability remained flat on arterials, with the BTI remaining at 22% in the AM Peak and decreasing from 21% to 20% in the PM Peak (a slight improvement in reliability). In contrast, freeway travel time reliability worsened significantly over the same period from 44% to 57% in the AM Peak and from 37% to 61% in the PM Peak (Table 4-2 and Figure 4-5), indicating a rising need to manage freeway demand (see San Francisco Freeway Management Study, underway).

Note: data collected April – May each year

Download chart data (CSV)

Roadway Segments Level of Service (LOS) and Buffer Time Index (BTI)

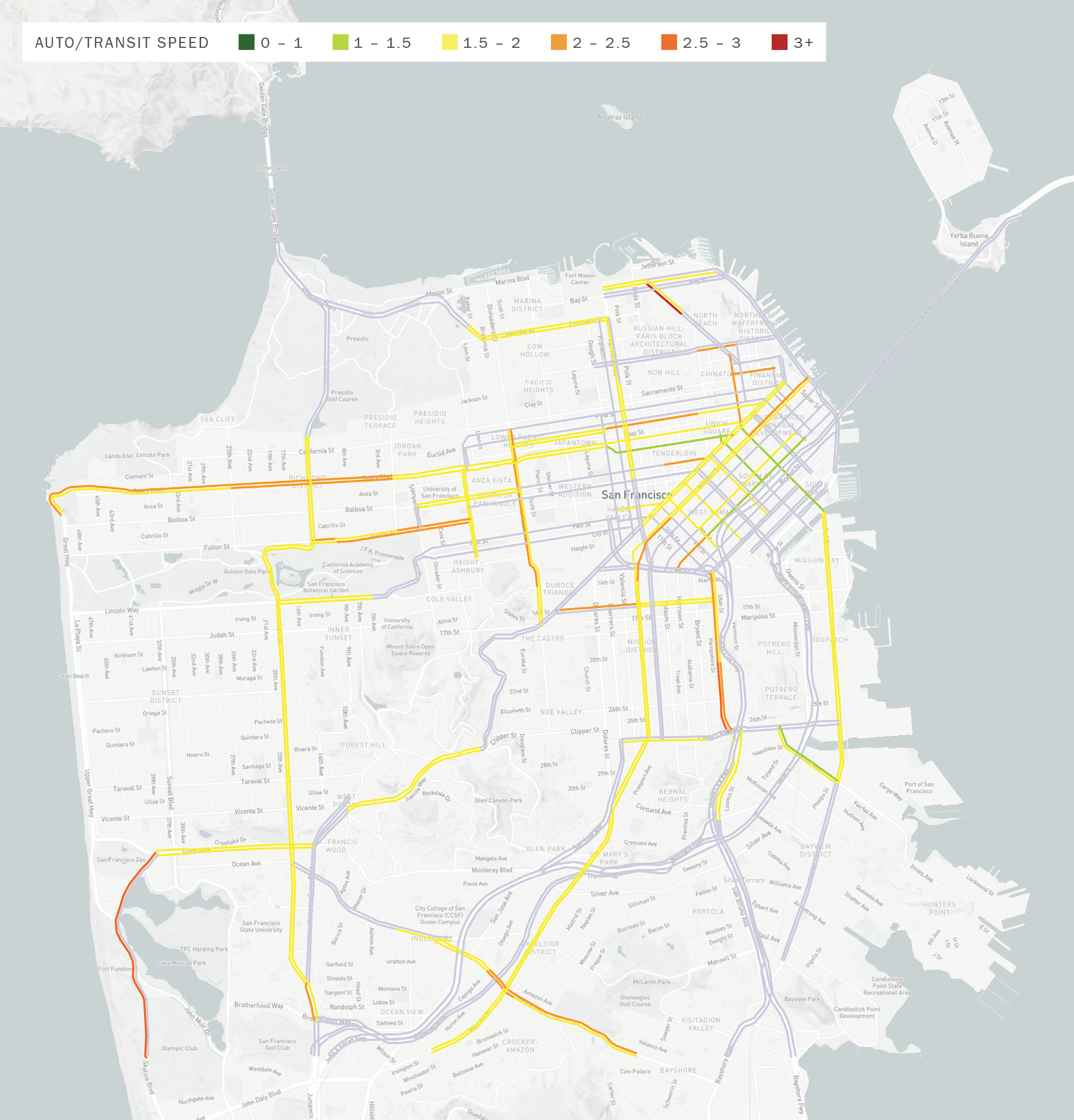

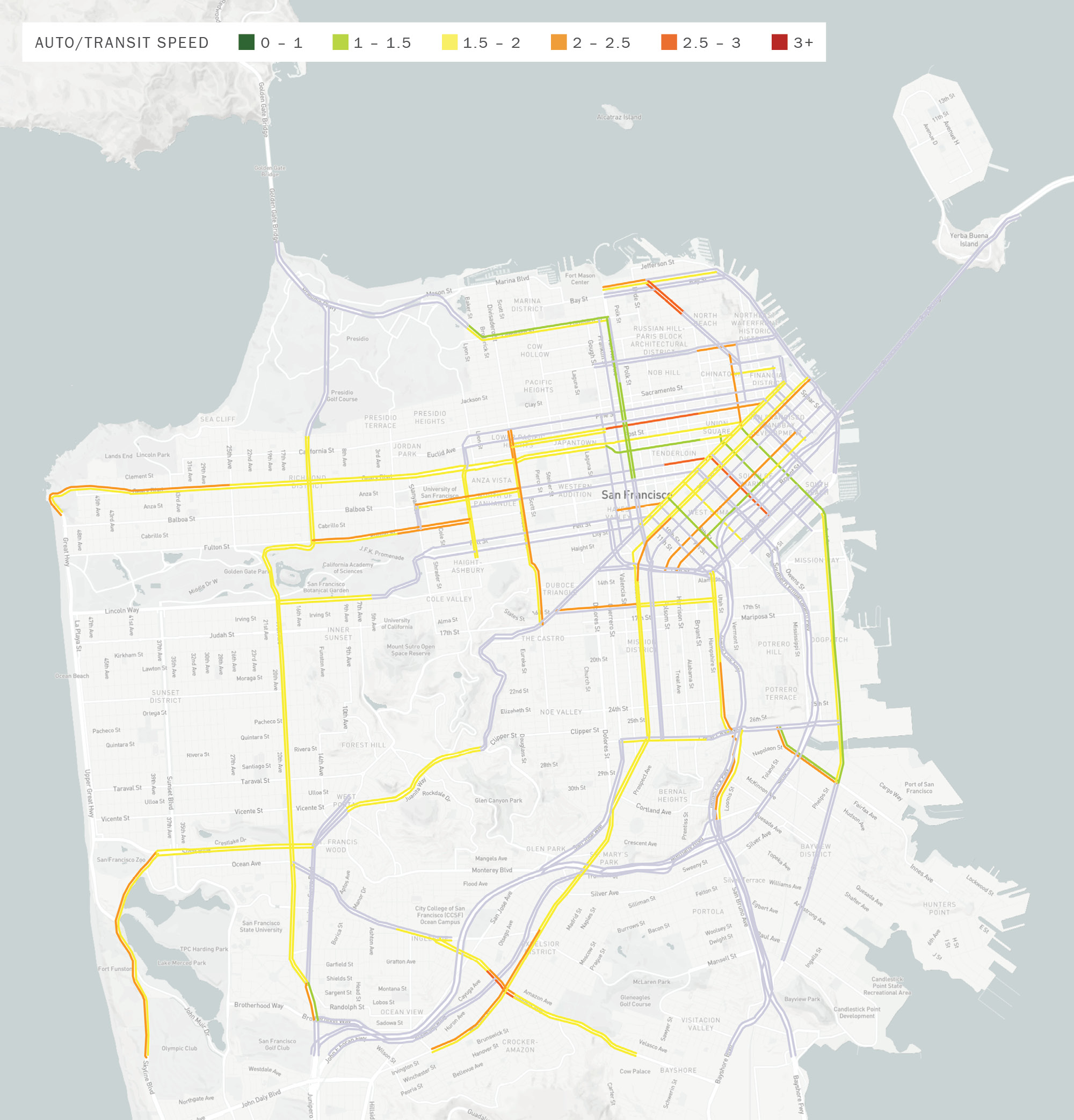

Figure 4-6 and Figure 4-7 show the LOS by roadway segment for the AM Peak and PM Peak, respectively. Full LOS monitoring results can be found in Appendix 1. Figure 4-8 and Figure 4-9 show the BTI by segment for AM Peak and PM Peak periods respectively. Interactive versions of these maps can be found at cmp.sfcta.org.

San Francisco Congestion Dashboard

The Transportation Authority maintains the San Francisco Congestion Dashboard (congestion.sfcta.org), shown in Figure 4-10. This tool reports many of the same roadway performance metrics as reported in the CMP congestion visualization, but with a much greater frequency (monthly instead of biennially) for a larger set of roadway segments, and at an hourly level as well as for the AM Peak and PM Peak periods starting in January 2020.

Deficiency Planning

There are no non-exempt LOS F CMP segments in this cycle for the AM Peak or PM Peaks. A section describing the exempt statuses of segments measured at LOS F in the current CMP cycle can be found in Appendix 1. For a detailed discussion regarding the CMP deficiency planning process, see the Deficiency Plans document on the Transportation Authority’s CMP reports & documents page.

4.4.2 Transit Coverage and Frequency

San Francisco has the most extensive transit coverage in the Bay Area. Refer to the websites of transit operators serving San FranciscoThe main transit operators in San Francisco include Muni, BART, Caltrain, AC Transit (Transbay service), SamTrans, and Golden Gate Transit (bus and ferry). for information on their service frequency and routing, which are still undergoing changes in the current post-COVID pandemic context.

Transit frequency refers to the number of transit vehicles (buses, trains, or ferries) per unit of time (e.g., 4 buses per hour). The inverse of the frequency is called “headway,” which is the time between transit vehicles (e.g., 15 minutes between buses).

Muni transit coverage by walk access at different levels of headways has been reported since the 2021 CMP cycle (and calculated for the April – May monitoring period biennially starting from 2017). This transit coverage metric reports the percent of San Francisco’s total population and total jobs that are within a five-minute walk of Muni transit service, using Muni’s General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS), and population and employment data derived from the US Census’ American Community Survey and San Francisco Planning Department.

Since 2023, more than 95% of San Francisco residents live within a five-minute walk of Muni service. Moreover, the share of the population within a five-minute walk of a Muni route with a five-minute headway increased from 27% in 2023 to 29% in 2025 for the AM Peak and from 20% in 2023 to 27% in 2025 for the PM Peak, though this is still lower than the pre-COVID population share within a five-minute walk of a Muni route with a five-minute headway (Figure 4-11 and Figure 4-12).

Download chart data (CSV)

Download chart data (CSV)

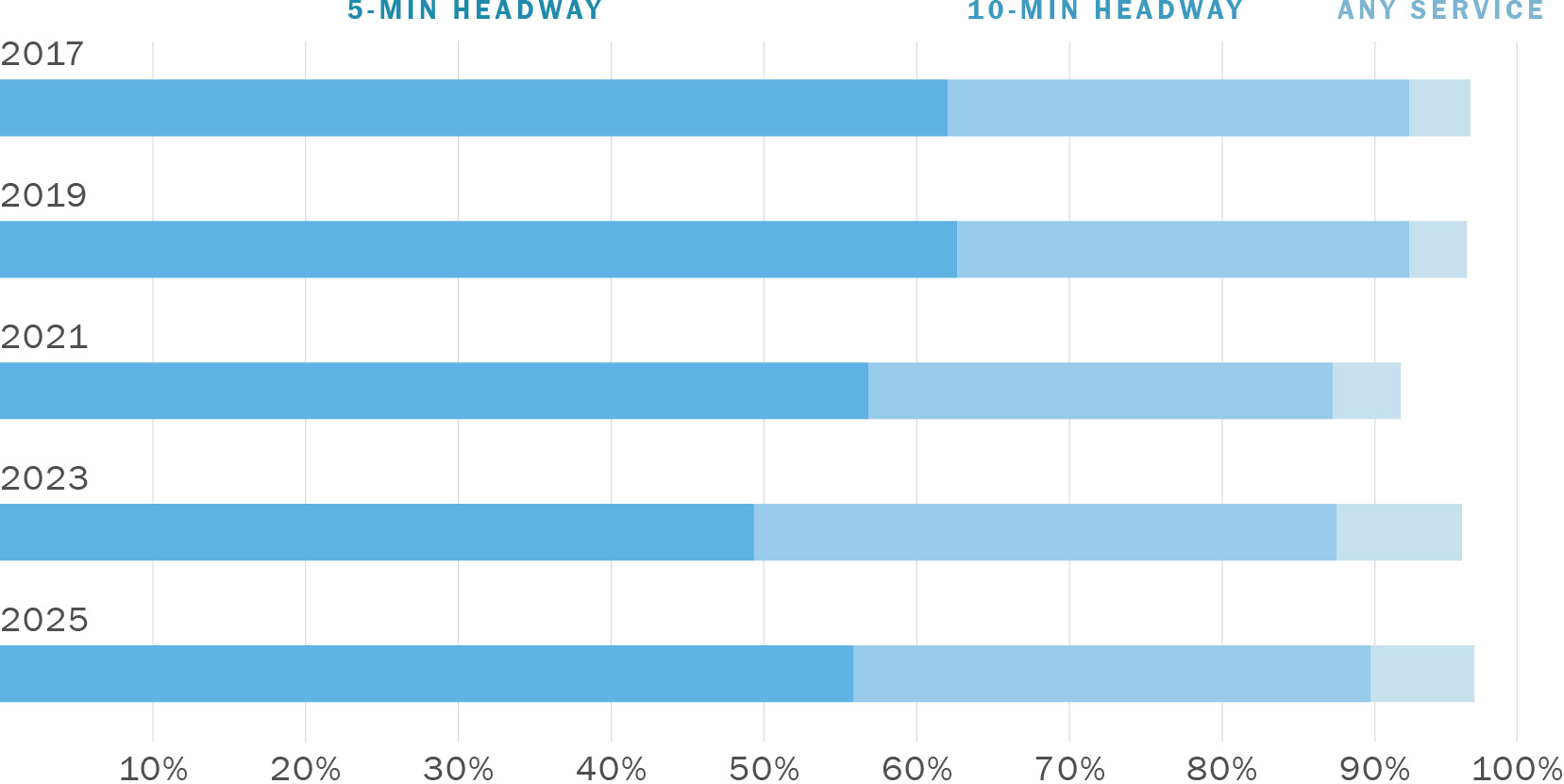

Muni transit coverage in terms of jobs for both the AM Peak and PM Peak periods show trends similar to those observed in population Muni transit coverage, with a larger increase between 2023 and 2025 in the share of jobs within a five-minute walk of a Muni route with a five-minute headway, from 50% to 56% (AM Peak) and from 41% to 56% (PM Peak) (Figure 4-13 and Figure 4-14).

Download chart data (CSV)

Download chart data (CSV)

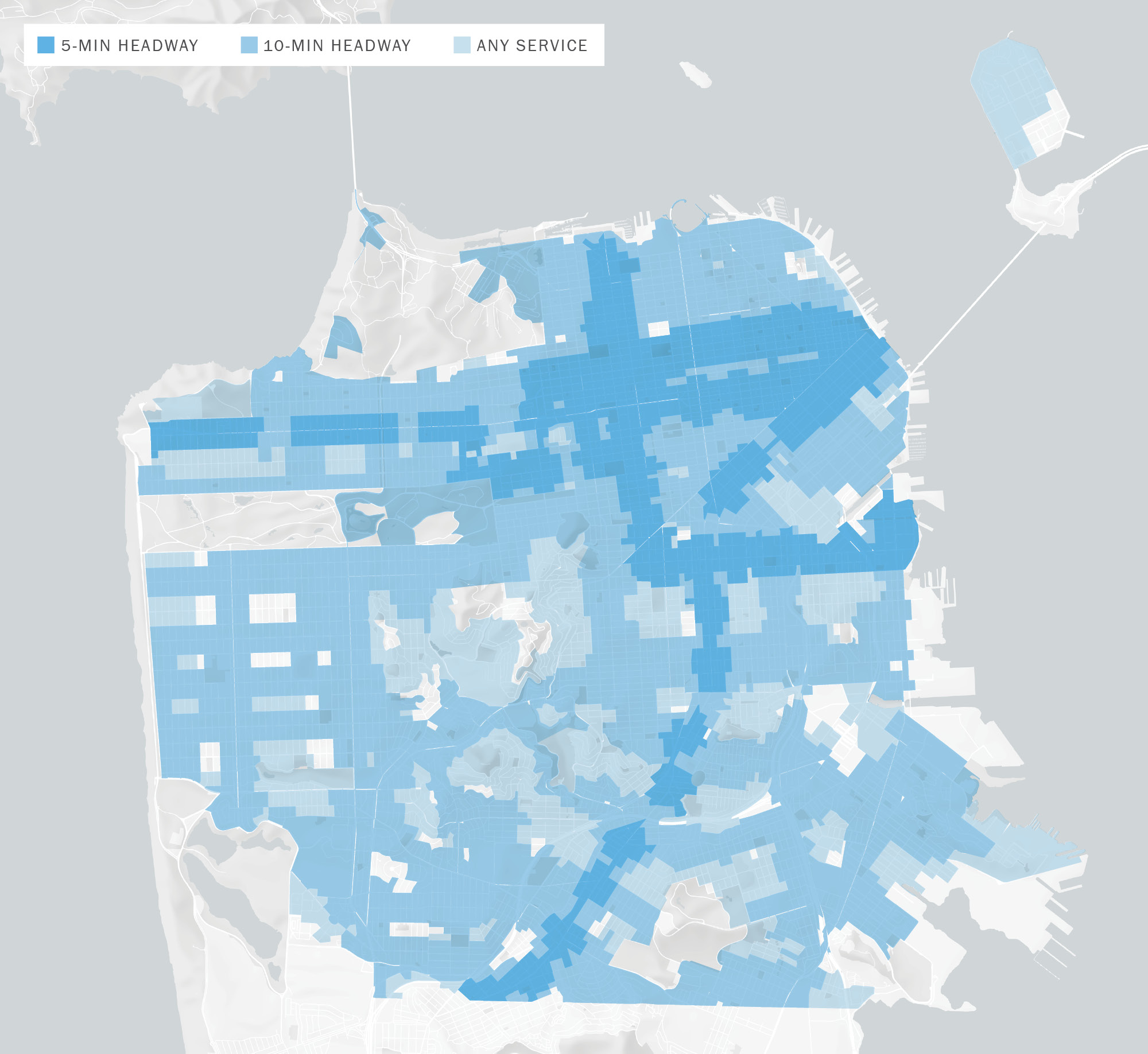

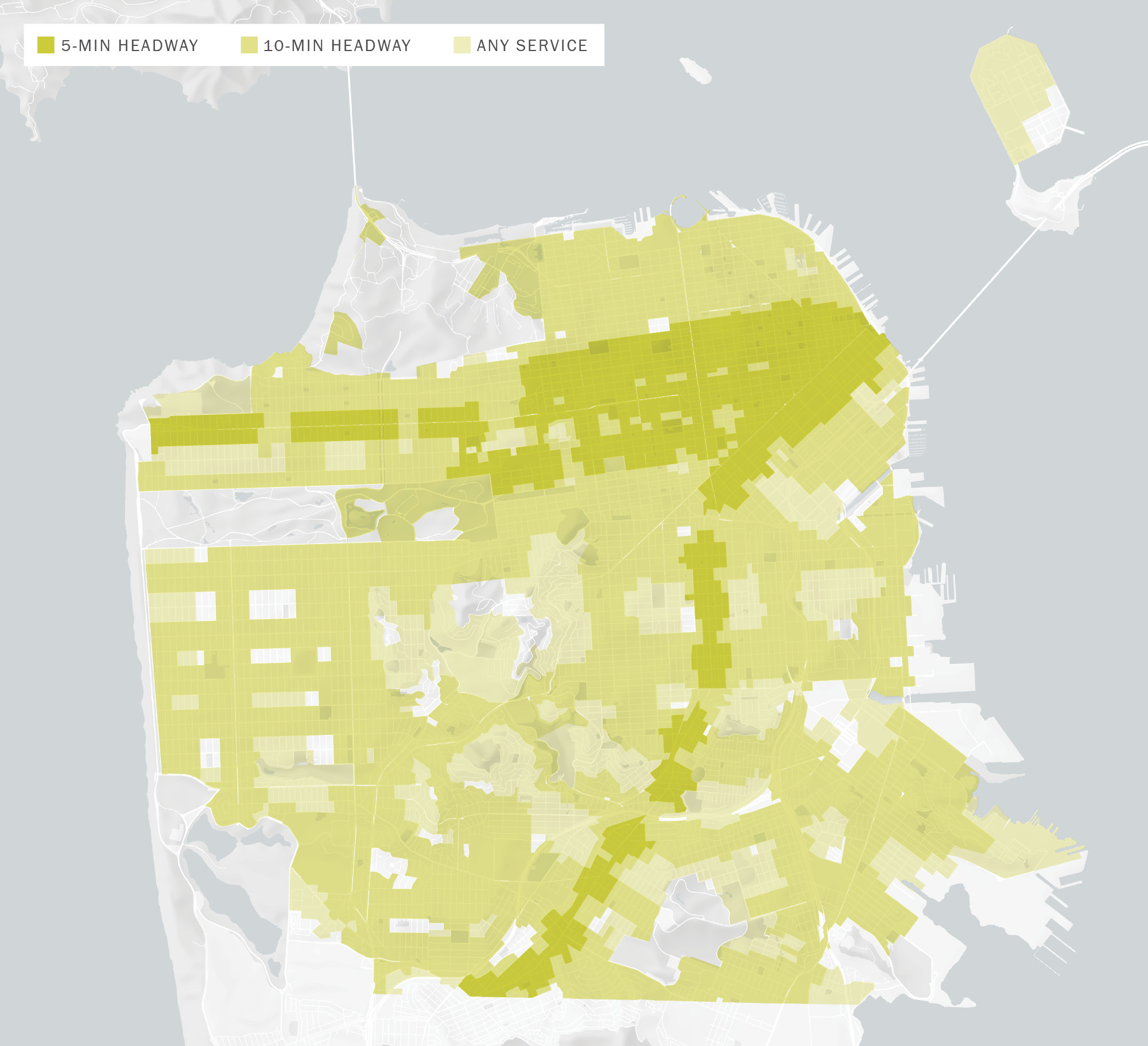

Figure 4-15 and Figure 4-16 show maps of Muni transit coverage in Spring 2025 by service frequency for the AM Peak and PM Peak periods respectively.

Note: data are from April – May of the monitoring year

Download map data (GeoPackage)

Note: data are from April – May of the monitoring year

Download map data (GeoPackage)

4.4.3 Interoperator Coordination

Linkages between transit services are provided by different operators (e.g., timed transfers at transit centers, joint fare cards, etc.) to facilitate the use of transit. Senate Bill 602 required that MTC, in coordination with the Bay Area’s Regional Transit Coordinating Committee (RTCC), develop rules and regulations for fare and schedule coordination in MTC’s nine-county Bay region. To that end, MTC has set up the Fare Integration Task Force in 2020 to further fare coordination and integration in the region. SB 1474, passed in 1996, set coordination objectives for the region’s transit services, and MTC has adopted Resolution 3055, Transit Coordination Implementation Plan, to comply with SB 1474. This MTC-led process is considered sufficient to meet the intent of CMP law regarding transit service coordination in the region. Compliance with MTC’s process by Muni and all other operators serving San Francisco will therefore constitute sufficient grounds for a finding of conformance with CMP transit coordination requirements.

4.5 Local Performance Measures

In measuring performance, we are measuring the ability of the system to satisfy the transportation needs of all San Franciscans, and we must therefore measure performance with reference to all types of transportation system users, including people riding transit, biking, and walking. Other than the outdated LOS standard as a performance measure for autos, there are few established standards for measuring system performance for people riding transit, biking, and walking. Multimodal performance data is increasingly needed for system performance measurement pursuant to updates of the San Francisco Transportation Plan and congestion management planning as well as for project planning, transportation impact analysis, and project prioritization. It is necessary to provide better information to the traveling public, as well as to inform policy decisions about funding of transportation projects and services.

The CMP includes nine types of local multimodal performance measures:

- Average Transit Speeds (Muni bus)

- Transit Speed Reliability (Muni bus)

- Auto/Transit Speed Ratio

- Multimodal Counts

- Screenline Volumes

- Bicycle Network Connectivity

- Street Safety

- Other Indicators

4.5.1 Average Transit Speeds (Muni bus)

Transit speeds are based on the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency’s (SFMTA) automatic passenger counter (APC) systems, which collect robust, real-time data on transit vehicle performance and ridership. For the current CMP cycle, APC data collected on Muni’s bus (diesel and trolley coach) fleet in the entire months of April and May 2025 were analyzed. The raw APC transit data utilized corresponded to the same AM Peak (7 – 9 a.m.) and PM Peak (4:30 – 6:30 p.m.) periods as the automobile LOS monitoring.

A detailed description of the APC data collection and analysis methodology can be found in Appendix 2.

Between 2023 and 2025, average transit travel speeds on the CMP network for both the AM Peak and PM Peak stayed constant at 9.0 MPH and 8.1 MPH, respectively. This is a positive outcome, given the rise in vehicle traffic and multimodal activity over this period. Transit speeds in 2025 are still higher than that during pre-COVID. Table 4-5 shows the change in average transit speeds. Figure 4-17 illustrates average bus speeds on CMP segments in the AM Peak and PM Peak periods since 2011. Appendix 2 contains the full results from all transit segments.

|

CATEGORY |

Peak PERIOD |

TIME-MEAN TRAVEL SPEED |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2023 |

2025 |

% CHANGE |

||

|

Arterial |

AM |

9.0 |

9.0 |

−0% |

|

PM |

8.1 |

8.1 |

+0% |

|

Note: Downtown Core in this figure is defined to include streets east of Franklin/Gough Streets, and north of the Central Freeway and Mission Creek. It also includes the streets immediately surrounding the Octavia Boulevard entrance/exit of the Central Freeway

Download chart data (CSV)

Table 4-6 and Table 4-7 shows CMP segments with the slowest transit speeds in the current CMP cycle. The slowest transit speed during the AM Peak period was 4.4 MPH on Turk from Market to Hyde. During the PM Peak period, the slowest transit speed was 3.7 MPH, also on Turk from Market to Hyde. 3% of the monitored CMP segments have a speed under 5 MPH in the AM Peak period, whereas 8% of the monitored CMP segments have a speed under 5 MPH in the PM Peak period.

Table 4-8 and Table 4-9 shows the CMP segments with the greatest relative changes in average bus speeds since the last CMP cycle. Between 2023 and 2025, the largest percentage decrease in transit speeds was −43% for the AM Peak, whereas for the PM Peak it was −28%. Figure 4-18 and Figure 4-19 show maps of monitored transit speeds by segment for the AM Peak and PM Peak.

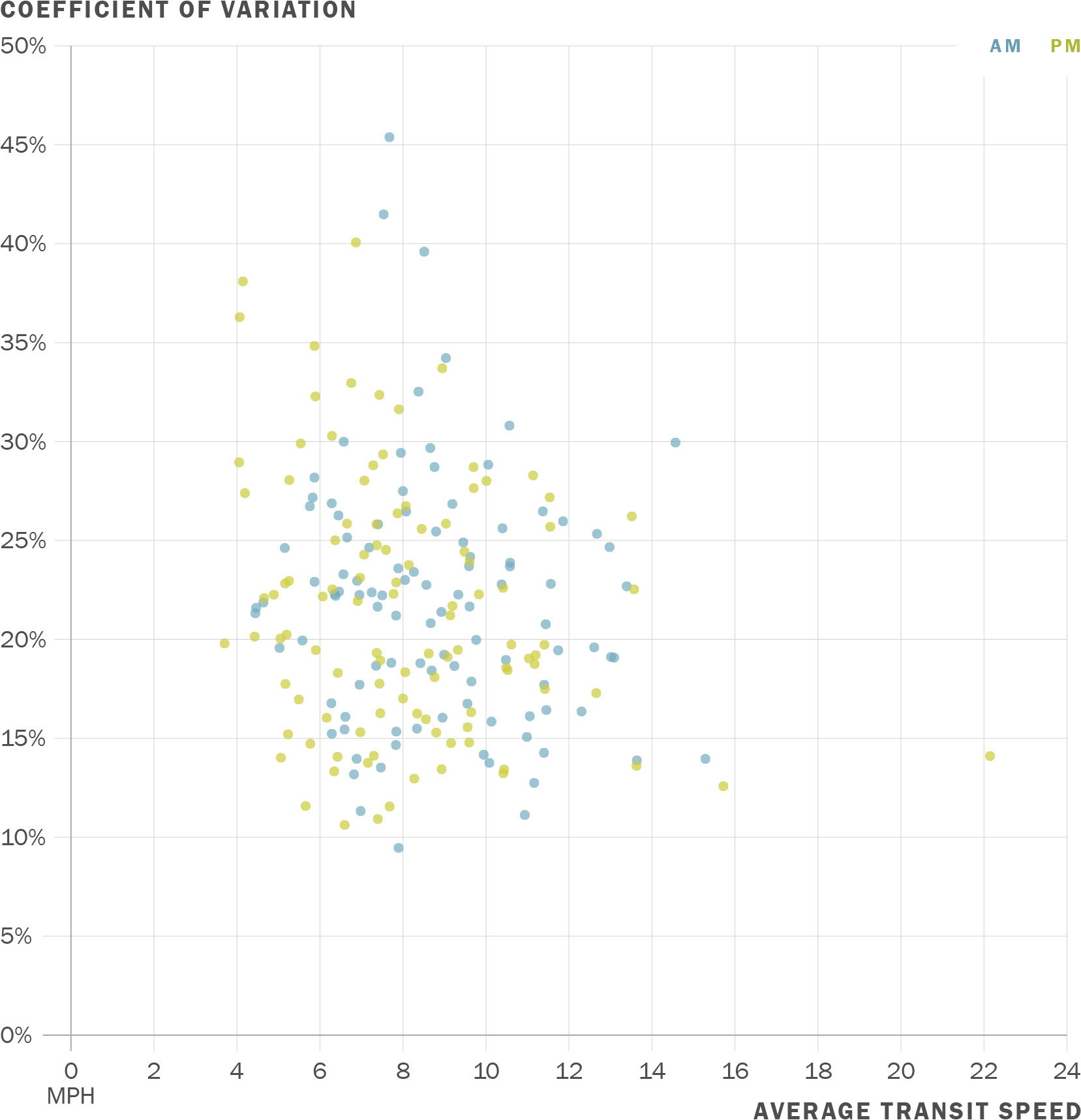

4.5.2 Transit Speed Reliability (Muni bus)

Beyond the average transit speed, San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency’s (SFMTA) automatic passenger counter (APC) data were also used to calculate transit speed reliability (variability). A detailed description of the APC data collection and analysis methodology can be found in Appendix 2. The standard deviation and coefficient of variation of travel time provide indicators of how reliable transit vehicle travel times are for a given segment. The standard deviation provides an absolute measure of variability, and indicates in minutes how far from the mean speeds typically range. The coefficient of variation (CV) is calculated by dividing the standard deviation by the average speed, thereby normalizing the results to compare relative variability between faster and slower segments. The CV is expressed as a percentage of the mean speed. A lower percentage indicates more reliable transit speeds. As with transit travel times, this is a positive trend and may reflect benefits from a variety of transit priority investments and traffic management strategies that were implemented during this time.

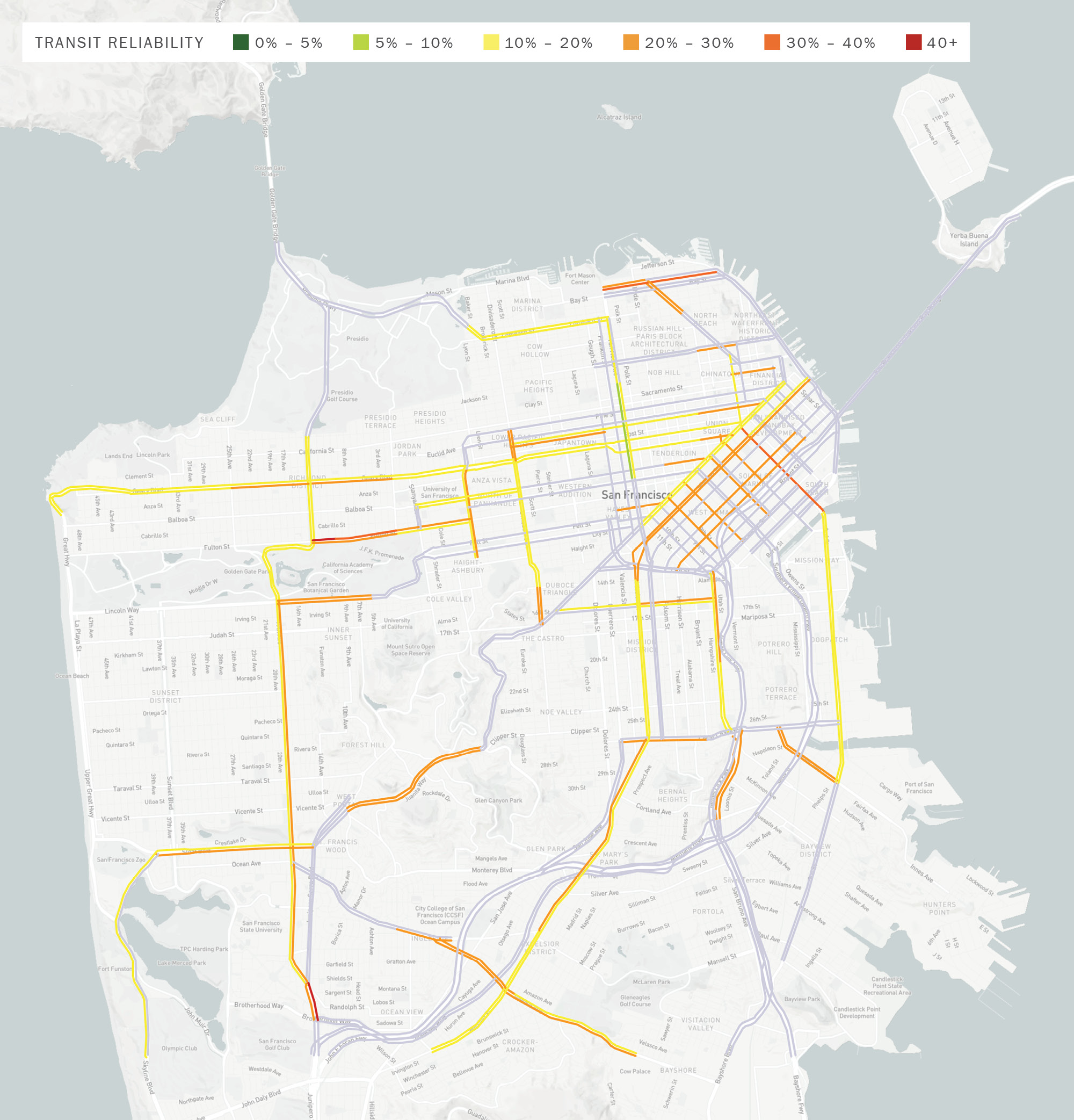

Transit reliability has stabilized (i.e. variability stayed the same) since 2023, staying at the same levels (21%) observed in 2019 and 2023 for both the AM Peak and PM Peak (Table 4-10 and Figure 4-20). With the average transit speeds in 2025 at 9.0 MPH (AM Peak) and 8.1 MPH (PM Peak), a CV of 21% means that approximately 70% of the time, a 3 mile transit trip would take between 15.8 and 24.2 minutes for the AM Peak, and between 17.6 and 26.9 minutes for the PM Peak.

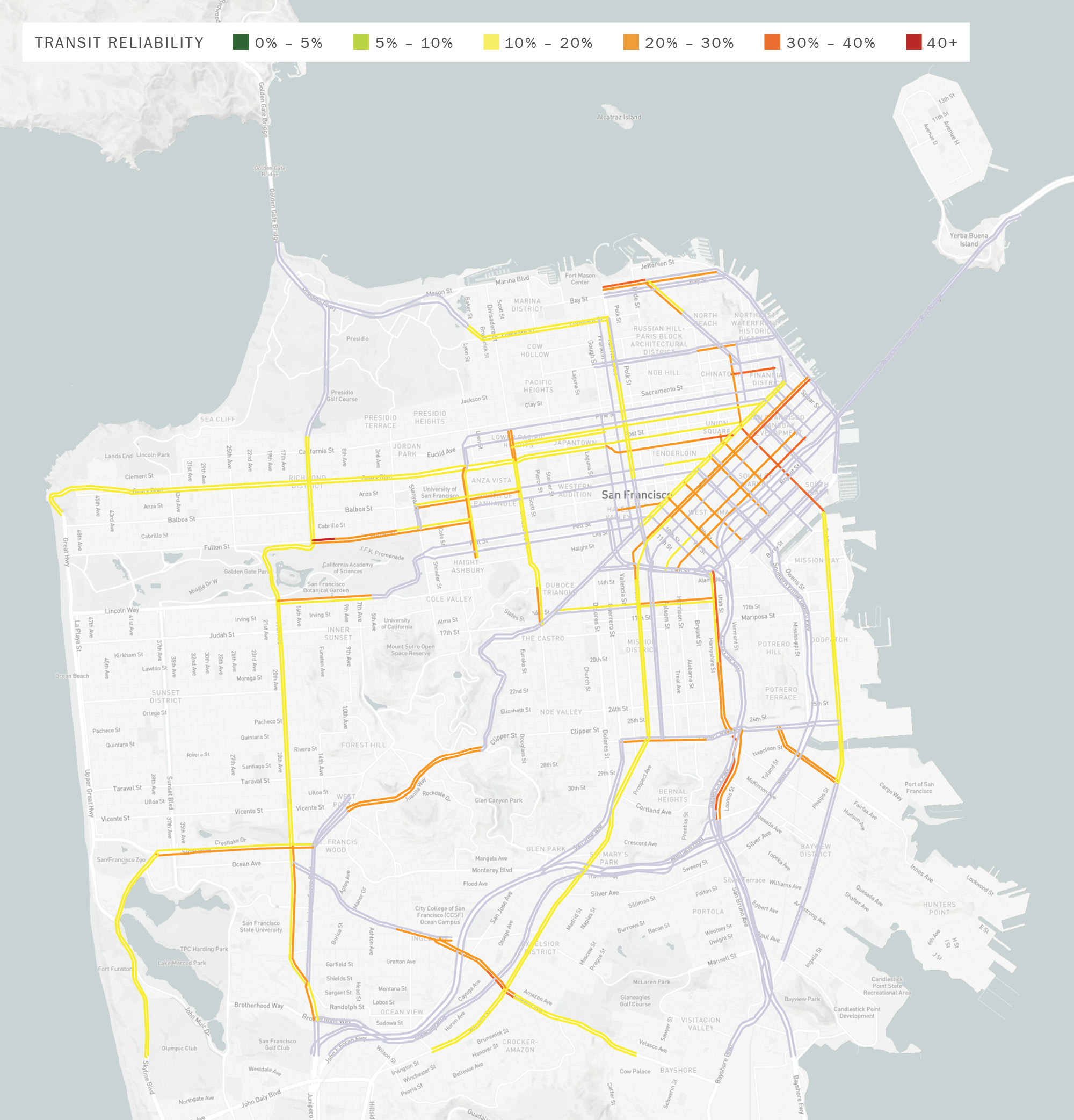

Segments with less reliable transit speeds (CV > 30%) are shown in Table 4-11 and Table 4-12. Figure 4-21 and Figure 4-22 show maps of transit reliability by segment for the AM Peak and PM Peak. Appendix 2 contains the full results from all transit segments.

|

2013 |

2015 |

2017 |

2019 |

2021 |

2023 |

2025 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AM |

16% |

16% |

16% |

21% |

23% |

21% |

21% |

|

PM |

16% |

18% |

18% |

21% |

25% |

21% |

21% |

Download chart data (CSV)

4.5.3 Auto/Transit Speed Ratio

In order to assess the competitiveness of transit with driving, the ratio of auto to transit speeds is calculated by comparing auto to transit speeds on the portions of the CMP network for which Muni data was available. Roadway speeds are derived from the INRIX data used for LOS monitoring and transit speeds are derived from APC data. The APC dataset is from April and May of 2025, the same period as the roadway LOS monitoring effort. For each segment, the ratio of auto-to-transit speed was calculated. A ratio of 2 would indicate that, for a particular segment, auto speeds are twice as fast as transit speeds. The ratio had been improving between 2013 and 2019. However, the ratio worsened since the start of the COVID pandemic and has been hovering around 1.7 – 1.8 since 2021 (Table 4-13 and Figure 4-23). Due to the Fall 2023 data anomaly described in section 4.4.1, the auto-to-transit speed ratio for 2025 cannot be directly compared to 2023.